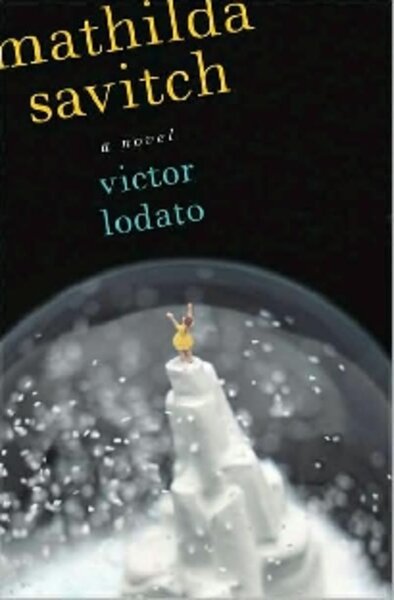

Mathilda Savitch

Loading...

Have you met Mathilda? If not, prepare to be – in equal measures – charmed and haunted. Because once you get this precocious teen’s sad, sharp voice in your head, it’s hard to get it out.

Mathilda is protagonist and narrator of Mathilda Savitch, a darkly humorous, aching tale of adolescence by playwright Victor Lodato. (Lodato apparently finished the book during the dead space created by the failure of one of his plays to make it into production. It was an excellent use of downtime.)

Mathilda, aka Mattie, is something of a latter-day Holden Caulfield. But she’s not an urbanite, nor is she exactly a failed child of privilege. She’s simply a clever, yearning young creature who’s been suddenly plunged into a tragedy deeper than she can fully fathom. Her older sister Helene is dead, either because she jumped or was pushed, under the wheels of a train.

The girls’ college professor parents have been destroyed by the tragedy, disappearing into their books and (in the case of Mattie’s mother) alcohol, gone to a place where Mattie cannot reach them. (A child at the time of 9/11, Mattie views life as a series of terrorist acts. “FEMA recommends talking to your parents about anxiety and other feelings,” she notes. “But Ma and Da can’t even hear me. It’s like they’re already in their own private bomb shelters in their heads.”)

Helene was, her sister tells us, both brainy and sexy, with a beautiful singing voice and a deep sense of compassion. (“If [Helene] could have adopted ten baby terrorists she would have done it in a heartbeat,” Mattie explains. “She had a real love for the downtrodden.”) Mattie, on the other hand, looks “sort of like a baby horse.” (Her mother tells her she’s “handsome” but she prefers “striking.”) Her prodigious intellect is restless (she wonders about everything from what wild dogs eat to what eternity would be like without humans) but she has yet to discover how to make a positive impression on the adult world.

Helene was the family star, gone now, having left behind only tapes of her singing (tapes no one can listen to now – “they’re the most dangerous thing in the world,” explains Mattie) and her abandoned e-mail account.

As the first anniversary of Helene’s death approaches, Mattie is desperately trying to get the attention of her parents, especially her mother. But somehow pinching the dog, breaking the dishes, and making unfunny jokes doesn’t seem to be working. Neither is Mattie connecting particularly well outside her home. Her beloved best friend, Anna, seems to be expanding her circle of friends away from Mattie, while boy-next-door and potential crush Kevin is mostly interested in Anna as well.

In the midst of her other failures, however, Mattie suddenly succeeds in discovering the password to Helene’s e-mail account, and as she delves deeper into her sister’s business, the unresolved questions about Helene’s death become more urgent – as does Mattie’s fear that she was at least partially to blame.

Along the way, other well-meaning adults try to intervene. There’s a nun who discusses prayer (“it probably would have been better to talk with a Krishna person, they’re usually younger,” Mattie thinks) and there’s a therapist, but, Mattie observes, “[H]e’s an old man, he grew up when the world was all turkey dinners and long walks in the moonlight. It’s a different time now.”

Mattie does not live in an uncaring world – just one that’s hard to connect with. “Most people are far away,” she observes. “Worse than stars.... You practically have to be an astronaut to live in a house on Earth.”

As this book counts down to its final chapters, you will find yourself turning the pages faster and faster to discover the truth about Helene’s death. Even more urgent, however, will be your need to know if Mattie ever finds her way back to her mother’s heart.

Marjorie Kehe is the Monitor’s book editor.