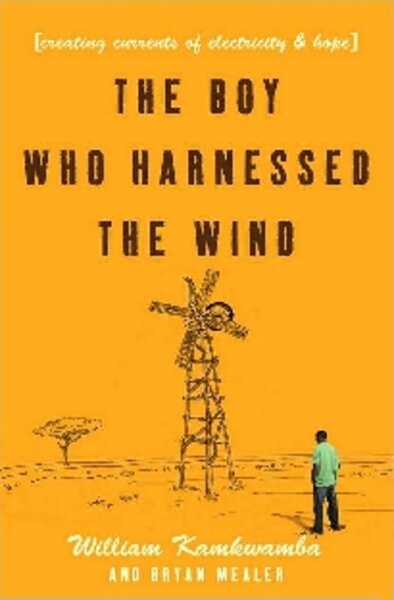

The Boy Who Harnessed the Wind

Loading...

If you thought physics was tough to grasp in high school, William Kamkwamba will seem like a hero to you. And really, he is. Forced to drop out of secondary school when his family couldn’t afford school fees, 14-year-old Kamkwamba used his free time to build a windmill that operated on principles of physics he managed to teach himself.

This windmill brought electricity to his home and eventually his entire village – a luxury that in Malawi is often reserved for the government and the wealthy.

To help Kamkwamba tell his story, journalist Bryan Mealer traveled back to Africa. He’d lived in the Congo for three years while working for the Associated Press. His first book, “All Things Must Fight To Live,” came out in 2008, and told the story of a country ravaged by war. This time Mealer started in Malawi. There, he spent months living with Kamkwamba’s family, interviewing friends and relatives. He spent hours learning about physics, magnets, and electricity so he could understand what Kamkwamba had created.

The result is The Boy Who Harnessed the Wind, an autobiography so moving that it is almost impossible to read without tears. In understated and simple prose, Kamkwamba and Mealer offer readers a tour through one Malawian boy’s inspiring life.

Kamkwamba’s inquisitive nature is apparent from the start. As a boy he takes apart radios to discover how they work, builds go-carts out of beer cartons, and creates screwdrivers with household materials. When he turns his inquisitive mind toward truck motors, he is taken aback that no one understands how they work. With the innocence that only a child can pull off, he wonders, “Really, how can you drive a truck and not know how it works?”

Then, as he fiddles and tinkers with all he can, tragedy strikes. A famine caused by drought ravages Malawi, and we see the results from Kamkwamba’s perspective. Friends are starving and people try to sell their children in the marketplace for food. Kamkwamba’s own family is reduced to eating one minuscule meal a day.

In a particularly disturbing scene, Kamkwamba recounts the day he witnessed mobs trampling children in their frantic push toward food. “If there’s anything I remember most about that day in Chamama,” he writes, “it’s the sound of crying babies.”

When the famine finally subsides, Kamkwamba, armed with American physics textbooks, starts construction on the windmill. His perseverance in creating this structure is coupled with altruism. Aiming to use the power of the windmill to pump water to the crops, he hopes to free his family from enslavement to the whims of weather.

Despite the highly charged events in Kamkwamba’s life, the telling of his story is surprisingly levelheaded. No sympathy is requested and no blame is bitterly assigned. In fact, a light humor darts in and out of the pages of this book, providing laughs where you wouldn’t have imagined even smiling. As the chief of Kamkwamba’s village begs the government to provide food during the famine and not toilets, Kamkwamba wryly asks the reader, “Because really, how can you use a toilet when you never eat?”

Pictures with captions are peppered throughout the book, giving the story depth and providing more humor. One image shows Kamkwamba as a toddler, with a caption explaining he was “surely plotting some mischief to cause [his] mother grief.”

After the windmill is constructed, Kamkwamba’s life becomes much more upbeat. He gets the chance to visit many places, among them New York City, California, and Las Vegas, (where Kamkwamba marvels that “women in their underpants serve free soda.”) When Kamkwamba is shown the Internet for the first time, his reaction is endearing.

If there is anything to complain about, it would be the simplifications. The authors describe bits of Malawian culture, like the roles of women and men, in mere sentences. The cycle of deforestation and poverty receives only a paragraph. A big slice of context seems to be missing, and Malawi is never more than a backdrop for this story.

Yet the infectious enthusiasm, heartbreaking tragedy, and final triumph make for an unforgettable story of success in the face of overwhelming odds. And as the story ends, it leaves us wondering about the future: Kamkwamba is accepted into a prestigious South African school where students who are considered future leaders of Africa have been hand-selected to attend.

As you read this book (I’d suggest keeping a box of tissues handy) you can be sure that William Kamkwamba’s future is bright. If this tale is any indication, we’ll be hearing his name again in the years ahead.

Kate Vander Wiede is an intern at the Improper Bostonian magazine.