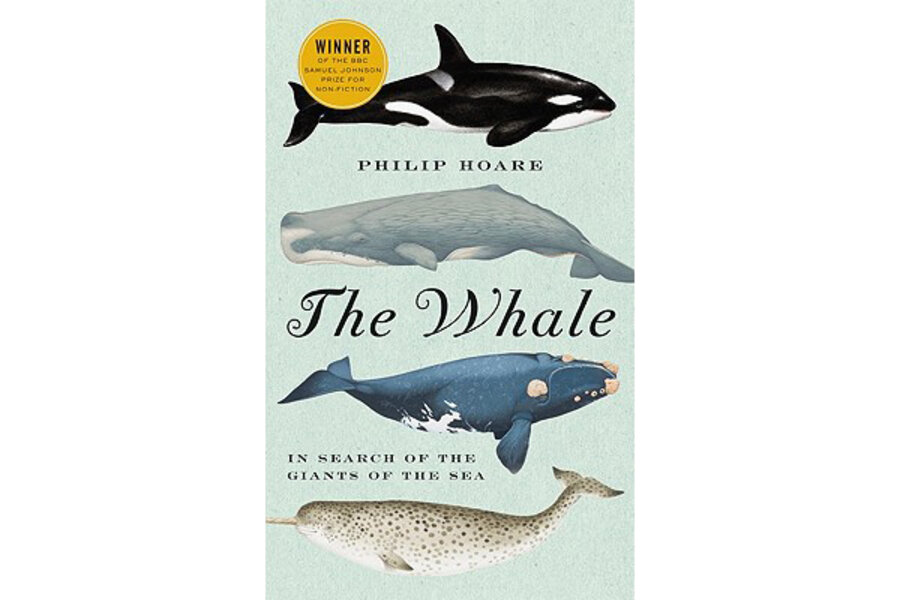

The Whale

Their ranks include some of the largest animals in the world and the loudest – if only we had the capacity to hear mating calls that can travel across the entire Atlantic Ocean.

Their brains are huge, their devotion to each other unmistakable, and their fate uncertain.

That’s interesting, sort of. Throw in “Thar she blows,” “Moby-Dick” and Shamu, and you know what you need to know about whales, right? What more is there?

British author Philip Hoare knows the answer: Majesty, mystery, and tragedy.

In The Whale, Hoare transforms his obsession with these mammoth creatures into an intricate exploration of history, literature, and science. It’s not a stretch to say he’s on a spiritual voyage to understand the whale’s place – and his– in the world.

Like the narrator of “Moby-Dick,” Hoare writes, “On my own uncertain journey, I sought to discover why I too felt haunted by the whale, by the forlorn expression on the beluga’s face, by the orca’s impotent fin, by the insistent images in my head.”

Hoare, who’s written six books on topics from Noël Coward to a Victorian-era utopia, wouldn’t deny that he has a love affair with the ocean and the largest animals in it. He long ago conquered his fear of the water and became an ocean aficionado. Now he feels claustrophobic and seems to develop what a poet called land-sickness when he’s away from the sea.

So it surprises no one when he travels in search of whales. He finds them, among other places, in the sea off Cape Cod: “I was amazed by the exuberant mastery of their own bodies, and the element in which they moved so elegantly. I envied them the fact that they were always swimming; that they were always free.”

As his book shows, however, whales are hardly free, and they haven’t been for hundreds of years. They’ve long been an object of human desire, a kind of precious metal on the hoof. Prized for their bounty, they found a formidable foe in man, although the whales found ways to fight back and kill whalers on occasion. (The book’s title in Britain is “Leviathan,” invoking the whale’s size and threat.)

As far back as the 1600s, Europeans knew the value of the whale: An epic painting shows dozens of Dutchmen clustering around (and on top of) a whale that had beached itself. Even a prince is on the scene, deploying a handkerchief “to protect his aristocratic nose from the stench.”

The oil from the heads of sperm whales fueled 5,000 streetlamps in 18th-century London, turning it into the most well-lit city in the world; the United States, meanwhile, sent a million gallons of whale oil to Europe each year. (Scientists still aren’t certain why oil is in blubber in the first place.) Whalebone was transformed into brush bristles and umbrellas, and even whale teeth became pieces of carved art known as scrimshaw, which President John Kennedy helped to popularize. He gave one to Greta Garbo, and his wife put another in his coffin.

Hoare’s focus is on the US, and he bounces around New England, making stops in the whaling strongholds of New Bedford, once the richest city in America, and Nantucket.

But nothing outside of the ocean gets more attention than the book “Moby-Dick,” which entrances Hoare. He’s enraptured by its “mysterious narrative power,” no longer “defeated by its size and scale, by its ambition,” and spends much time chronicling the life of its author and analyzing the words within.

Hoare’s own attempts to create grand poetic prose aren’t as successful as Melville’s, especially when they’re larded with sentimentality. “Theirs is a landless race,” begins one gauzy sentence about whales, while another boldly claims that they’re “a symbol of innocence in an age of threat.”

Hoare is on somewhat firmer ground when he seeks and finds familiar emotions in whales, even though he acknowledges that it “oversteps boundaries” to humanize them.

They bear the dying on their shoulders and seem to grieve; they become furiously angry; they seem to have a sense of fun and delight as they frolic in the sea.

And back in 2004, The New York Times reported on the tracking of a whale’s 12-year odyssey in the Pacific Ocean. It called out “with a voice unlike any other whale’s,” and got no answer. Its brain might have gotten its wires crossed, dooming the whale to forever seek a mate that will never hear it.

Can a whale feel loneliness? Neither Philip Hoare nor Herman Melville are equipped to answer that question. But thanks to “The Whale,” readers are sure to wonder what lies beneath.

Randy Dotinga is a freelance writer in San Diego.

Join the Monitor's book discussion on Twitter.