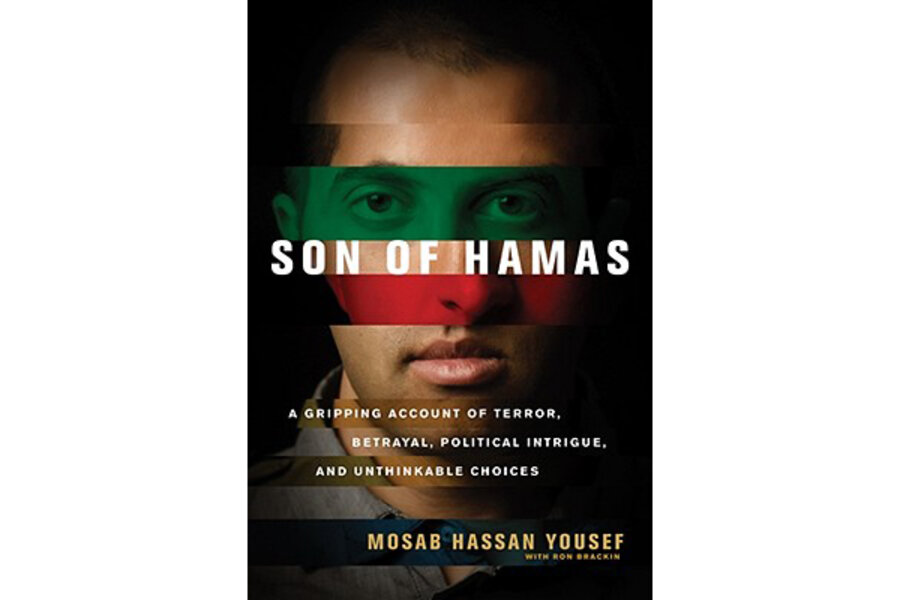

Son of Hamas

Loading...

Son of Hamas, a story that feels like a long-lost Abrahamic fable that has morphed into contemporary history, is explosive. To be sure, the writing is clumsy in places, but that occasional distraction does nothing to blunt the impact of the material.

The book is the autobiography of 32-year-old Mosab Hassan Yousef, the eldest son of Hamas cofounder Sheikh Hassan Yousef. And what a tale Mosab has to tell. As a child, he was a stone-throwing participant in the first intifada, the Palestinian uprising against Israeli occupation that rocked Israel and the Palestinian territories in the early 1990s. Although Mosab had a tender relationship with his father – a man widely regarded as a voice of moderation within Hamas and portrayed by Mosab as a gentle human being – Mosab himself is nearly consumed with hatred fed by the bitter frustration of life under Israeli occupation.

When he gets hauled into Israeli prison on the suspicion that he is preparing a terrorist attack, Mosab strikes a deal with an Israeli intelligence agent and becomes an informant, a move he sees as a way to get out of the clink sooner rather than later. While things don’t work out as pleasantly in the near term as Mosab might have liked, his departure begins a sort of slow unraveling. His feeling of powerlessness at the senseless death around him pushes into deeper and deeper connections with his new Israeli colleagues.

Code-named the “Green Prince” for his position amid the upper echelons of Hamas (whose signature color is green), Mosab goes on to help Israeli intelligence imprison scads of Palestinian resistance leaders (including Marwan Barghouti, who many analysts now believe will play a leading role in the future of Palestinian politics) and head off suicide bombings. At the same time, he wrestles with the agonizing realization that his beloved father will stay alive only if Mosab uses his influence to keep him in the safest possible place: an Israeli prison, where he remains to this day.

Mosab’s transformation into the Green Prince carries a spiritual shift as well: he becomes a Christian. Mosab is not shy about laying out answers to the moral dilemmas he faces. It’s an aspect of the book that is endearing at some moments but preachy and an impediment to the flow of the narrative in others.

There are more than a few vignettes in “Son of Hamas” that will make your heart race. When a cell of would-be suicide bombers seeks out Mosab’s assistance in securing accommodation before their attacks, the listening equipment he stows in their room allows the Shin Bet (the Israeli Security Agency) to hear the men discuss their impending murderous immolation. “Everyone wanted to be first, so they didn’t have to watch their friends die,” Mosab writes. “We were listening to dead men talking.”

In another instance, Mosab must make a harrowing trek into an Israeli military base to meet with his handlers – without alerting the proper authorities.

There could be many more such moments if each unbelievable escapade were given a little space to breathe and build. But just as your heart is set to race, Mosab typically slows the pace with a hint that the Lord has his back. Divine intervention occurs regularly throughout the book – often hamstringing the drama just at the diciest moments.

Readers should be forewarned that within the context of debate about the Israeli-Palestinian issue, Mosab’s views coincide much more strongly with the Israeli right than with almost any Palestinian faction. His blathering about the nature of Islam reproduces much of the worst of American Islamophobic discourse, while his take on Palestinian-Israeli struggles often reflect hackneyed pablum about the corrupt, opportunistic nature of Palestinian politics.

Reading between the lines, it is easy to question the degree to which Mosab was actually central to the Hamas hierarchy. By 2004, he writes, “Somehow, I had become a key contact for the entire Palestinian network of parties, sects, organizations, and cells – including terrorist cells.” Two pages later, however, he laments that, “after a decade of arrests, imprisonments, and assassinations, the Shin Bet still had no clue who was actually in charge of Hamas. None of us did.”

Great literary cloth has been spun from the mystique of the Israeli intelligence services and their perpetual back-and-forth with their largely Arab foes. George Jonas’s “Vengeance,” which followed the Mossad’s hunting and killing of the Palestinians suspected of the 1972 Munich Olympic attacks, eventually became the Steven Spielberg-directed film “Munich.” Paul McGeough’s “Kill Khalid,” about the inner workings of Hamas and the life of its enigmatic leader Khalid Mishal, turns a thrilleresque narrative about a failed Israeli hit on Mishal into a deep-diving history of the movement.

“Son of Hamas” can’t match the narrative or intellectual power of these predecessors. But through its earnest, intimate style, the book offers an easily accessible entry point to Israeli-Palestinian emotional strife and political intrigue. Although sometimes given to simplistic renderings of a very complex reality, Mosab’s unique journey and poignant moral touchstones makes “Son of Hamas” worth a second look.

David Grant is freelance writer in Baltimore.