Jane's Fame

Loading...

Why is the world obsessed with Jane Austen? What is it about her life and novels that propelled her from a Regency writer of limited renown to a cottage industry? The answer, like Austen’s novels, is deceptively simple, masking a complex web of factors, from her marketing by her family to the lack of verifiable information that makes it so easy for us to project our fantasies onto her.

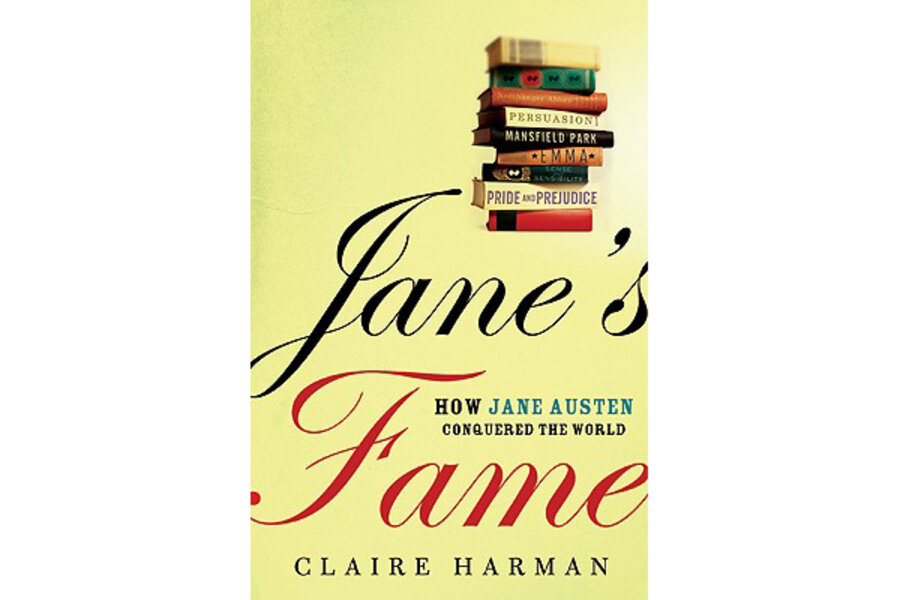

In Jane’s Fame: How Jane Austen Conquered the World, with its only partly tongue-in-cheek subtitle, Claire Harman traces the phenomenon that is “Jane.” Neither literary criticism nor biography, “Jane’s Fame” instead tracks Austen’s image from a novelist who had difficulty getting published and opened to mixed reviews to that rare combination of canonized and cult author, coupled with both Shakespeare and zombies. (Harman points us to an amusing YouTube montage of bodice-ripper scenes from Austen film adaptations set to “It’s Raining Men,” easily Googled as of this writing.)

The first take on Austen came from her nephew, James Edward Austen-Leigh, who cast his aunt in the role of the ideal Victorian woman – modest, unambitious, and certainly not inclined to let writing interfere with her “domestic duties.” It was from Austen-Leigh’s “Memoir of Jane Austen” that the image of Jane’s fiction as a “little bit of Ivory” began, creating an association of “smallness” with the novels that took on a life of its own, clinging to Austen herself, who, ironically, was probably tall.

The family’s initial reluctance to reveal Jane Austen’s true face to the public provided the perfect mystique for speculation in the ages to follow.

Though her focus is on the stories others have told of Austen, Harman has her own story to tell, too. Harman’s Austen is neither sweet nor retiring, but a fire poker – a metaphor evoked by her bearing and manner, according to a contemporary visiting her household. Think tall, strong. and “formidable,” not small and sweet.

Austen-Leigh is a convenient straw man and Harman clearly enjoys quoting his inaccuracies only to knock them down. Austen, she argues, was more hardheaded businesswoman than the self-effacing maiden aunt Austen-Leigh would have us believe. Harman also emphasizes the literary nature of the household that fueled her ambition. Austen’s oldest brother, who published a short-lived literary journal, was an aspiring poet and considered the writer of the family by their mother. Her cousin was close to the celebrated novelist Fanny Burney d’Arblay and this proximity may have influenced Austen both artistically and in her approach to selling her novels. Likewise, Austen’s art did not come effortlessly, but through extensive drafting and revision, involving pinning slips of paper with new text to an earlier draft, “a nineteenth-century version of cut and paste.” The absence of historical markers or political controversies in her novels, rather than being a deficiency, may have stemmed from an anxiety over becoming dated, so conscious was Austen of her reading public and so frustrated was she by the long delay in the publication of “Northanger Abbey,” the first and most topical of her works.

Such delays, though discouraging, may have helped Austen to hone her stylistic innovation. “The longer Austen remained unpublished,” Harman posits, “the more experimental she became, and the more license she assumed with bold, brilliant moves.” Without a readership other than her intimates, Austen remained free to develop her distinctive voice.

Major literary figures that followed tended to fall into camps that either disparaged or lauded Austen – Mark Twain among the former (but then, who did he like?), and her heirs apparent, James, Forster, and Woolf, among the latter. But the image of World War I soldiers reading Austen in the trenches, or Churchill turning to “Pride and Prejudice” for comfort while bedridden with influenza in the darkest days of 1943, most vividly convey Austen’s position as a cornerstone of British culture.

Harman notes Austen’s universal appeal, too, as testified to by the Parisian anarchist Félix Fénéon, who read “Northanger Abbey” while in prison and was so taken with its class critique that he translated it into French, thereby becoming Austen’s first Marxist critic.

Harman caps her book by analyzing our culture’s current Austen-mania generated by the proliferation of film adaptations. Since the most salient take-away conveyed by “Jane’s Fame” is that these biopics, prequels, and sequels reflect more on us than they do on Austen herself, one can only wonder what future generations will deduce from “Pride and Prejudice and Zombies” or “Mr. Darcy, Vampire,” about the mores of the early 21st century.

Elizabeth Toohey teaches Women’s Studies and Postwar American Literature at Principia College in Elsah, Ill.