The Diamond Dog

Loading...

When he gave poetry readings, Robert Frost told the poets in the audience to do it the way he did. Don’t mumble, he said, look up from the page, pause between poems, and say something about each one before reading it. Anyone who has ever sat through a high-speed poetry reading and left bewildered will wish that more poets would take Frost’s advice to heart.

Poetry is the most compressed of the arts, so what Frost was saying is that it’s just plain good manners to set the poem up, especially if you want the audience to get anything from it. If that’s good advice regarding individual poems, it’s equally good for entire collections, though few poets introducing their work are likely to go as far as Diane Wakoski does in the essay that begins her latest book, The Diamond Dog.

Wakoski has been writing poems for about 50 years; her first collection, “Coins & Coffins,” appeared in 1962. Her work is often associated with the Deep Image school, with its allegiance to the Jungian imagery said to comprise the collective unconscious, as well as the Confessional and Beat movements in poetry. Her best-known book, “The Motorcycle Betrayal Poems,” appeared in 1971 and deals with, as Wakoski notes in her dedicatory statement to that volume, “all those men who betrayed me at one time or another.”

All of these – the Jungian images, the tendency to confess, the wild leaps and unruly rhythms of the Beat poets, the theme of abandonment – figure in “The Diamond Dog.” By now, though, Wakoski is able to look back over her 22 books and connect these concerns in the essay called “Creating a Personal Mythology” that begins the book. Here she provides a career perspective that her fans will welcome. Just as important, she describes a way of writing that young poets will be able to make their own.

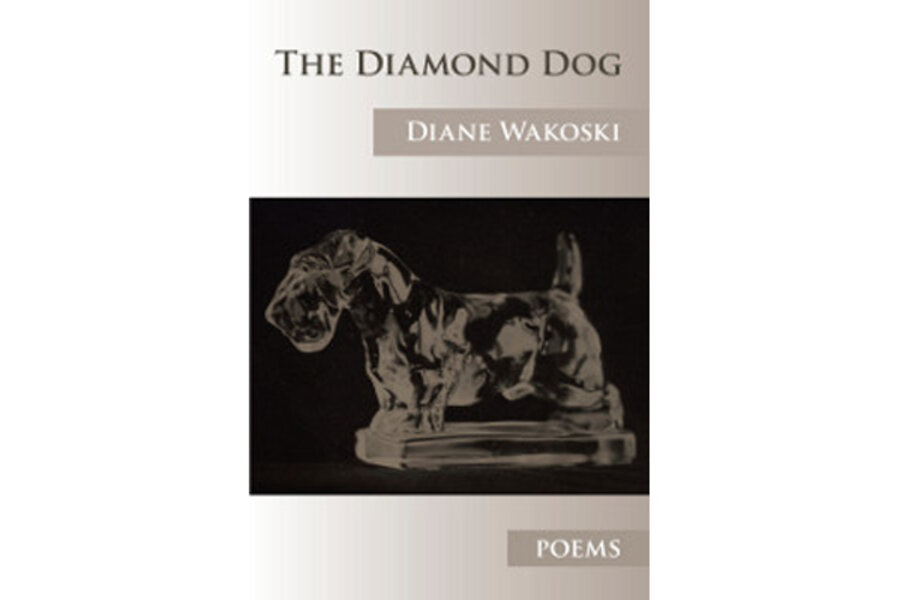

The image of the Diamond Dog that dominates these poems comes, Wakoski explains, from a dream she had after her father abandoned the family when the poet was 13. In the dream, “a little Scottie-shaped dog” made from a huge diamond springs from an ash heap and follows the disappearing father, becoming a link between him and his daughter-poet.

Now the poems in “The Diamond Dog” serve as chapters in the myth she makes of her own life. “In creating a personal mythology,” Wakoski says, “poets can give themselves to their bigger stories, imbuing them with greater intimacy or poignancy, using the small details of our everyday experiences.”

And so poet pursues pooch through time (childhood, young womanhood, the present) and space (California, Greece, the underworld). Along the way she brushes past such poets of her generation as Robert Creeley and Charles Olson, but she also acknowledges the place in her life of Plato and Montaigne and Proust, of Leonard Cohen and Bob Dylan. The Diamond Dog doesn’t appear in every poem; then again, he’s here to be chased, not caught.

Eventually, of course, he is, or if not caught, exactly, at least understood in a new way. “You weren’t following./ You were leading,” writes Wakoski, that is, guiding her toward her life as a poet. With insight, she finds the balance she’s been seeking, and she is able to realize how lucky she is “to have a father who sailed away, rather than one/ who was a disappointment in the flesh.”

Wakoski’s rhythms are jazzy and easygoing; they’re accepting of the world in all its crunchy variety, and they invite the reader to accept as well. The best way to describe her poetics is to say that she asks the reader to go for a walk with her. A poem called “Walking” has as its epigraph the words “Music’s a wood you walk through” (from novelist David Mitchell), and here the poet walks through the music she makes of her own experiences, her lines swelling and falling as she thinks of Chekhov, Tolstoy, Rachmaninoff, a gift from an old friend, the cup of tea she hopes to have later, and, of course, a certain mythological canine.

Speaking of hot beverages, Wakoski is not everybody’s cuppa; one online reviewer describes her obsession with unreliable men as “whiny.” But she is still an important and engaging poet, one whose bloodlines go back to the early history of contemporary free verse. And this book in particular should have a special relevance for young poets and their teachers, since it shows how, through personal mythmaking, one can bring out of the heat and pressure of one’s life a hidden beauty.

David Kirby is the co-editor with Barbara Hamby of “Seriously Funny: Poems About Love, Death, Religion, Art, Politics, Sex, and Everything Else.”