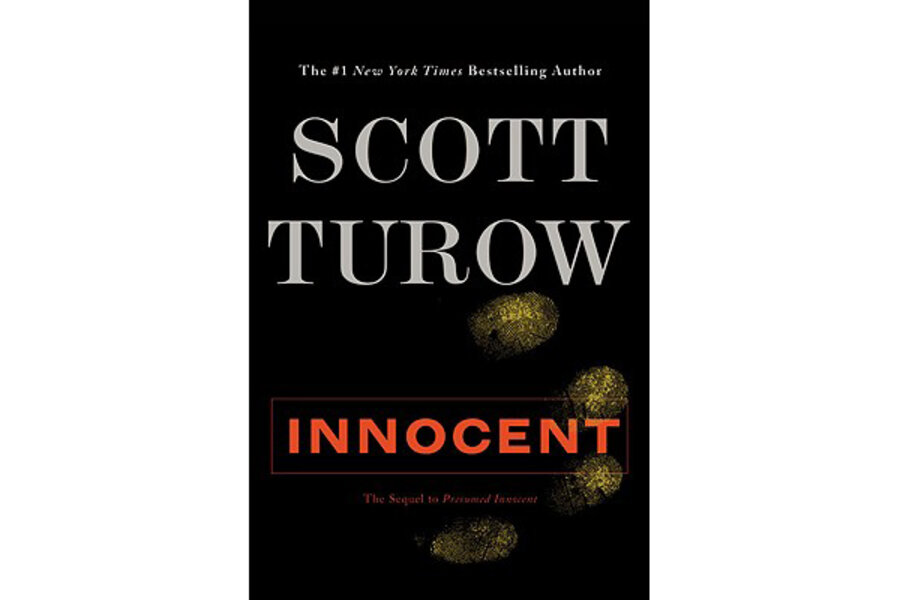

Innocent

Loading...

People don’t change. Or maybe they do.

In Innocent, Scott Turow uses that do-they-or-don’t-they notion to fashion a superb sequel to his 1987 blockbuster, “Presumed Innocent.” The earlier book became a bestseller, launched the still-popular legal thriller genre, and led to a successful movie adaptation starring Harrison Ford.

Even as John Grisham and dozens of others followed similar paths to the best-seller lists, Turow resisted the urge to repeat his winning formula over and over again. He took his time with each new novel, eschewing the book-a-year cycle publishers prefer for brand-name authors. Sure, Turow often stayed in his fictionalized version of Chicago, the corrupt and brooding Kindle County, but he moved on to much different stories, keeping readers off balance while keeping a close eye on developing characters interesting and intriguing enough to match his brisk courtroom plots.

With “Innocent,” Turow returns, 20 years later, to the scene of his breakthrough novel. Former rival deputy prosecutors Rusty Sabich and Tommy Molto, stars of the first book, are headed for another blockbuster murder trial.

Though “Innocent” is a richer read for those who have read “Presumed Innocent,” it stands alone with ease. Turow sprinkles in enough back story to reveal why Rusty, now an appellate judge, and Tommy, the acting prosecuting attorney, remain wary of one another.

Rusty, as millions of readers will remember, endured a searing murder trial in the earlier book. While he won an acquittal, he lost almost everything else. The rape and murder of Carolyn Polhemus, Rusty’s co-worker and former mistress, rocked his marriage and family.

Tommy presided over the explosive case against Rusty, navigating a maze of wobbly investigation and situational ethics before being censured himself for mishandling evidence. Although Rusty later helped Tommy get his job back, animosity lingers on both sides. Rusty resents Tommy’s continuing belief that he got away with murder while Tommy seethes over the acquittal and the collateral career damage it caused.

History, or, in this case, bitter history, repeats itself two decades later.

This time, Rusty is accused of murdering his wife, a miserable but brilliant woman who never recovered from the earlier trial – or the effects of her husband’s affair. For many years afterward, Barbara Sabich controlled and manipulated her husband and smothered their son Nat. Now Nat is out of the house and husband and wife live in a state of uneasy détente.

Six weeks before voters decide whether Rusty wins a spot on the state supreme court, Barbara dies. At first, her death is ruled to be of natural causes.

Soon enough, though, whispers abound. When Barbara died, Rusty sat in their bedroom, next to the corpse, for 23 hours before alerting anyone. He claimed shock and grief. Barbara’s unexpected, unexplained death fuels suspicion for other reasons as well. She was blessed with youthful looks and was known for her dedicated exercise regimen.

Then, too, subsequent poking around reveals that Rusty had consulted with a divorce lawyer just before Barbara’s death. He has also been followed to various hotels around town, where he stays for a couple of hours in the afternoon and then dashes away. That obvious sign of marital trouble is compounded when investigators discover Rusty has taken a test for sexually transmitted diseases.

Bit by bit, Tommy, spurred by his hard-charging and ambitious deputy, assembles a murder case. Powerful drugs missed in the coroner’s toxicology scan, the fraying marriage, and revelations of Rusty’s affair point to him as the killer.

Of course, Turow never paints in black and white, preferring the gray skies that cloud so many Midwestern winters. Which means Tommy, not just Rusty, brings considerable baggage, political trepidation, and extenuating circumstances to the case.

To this heady concoction Turow adds a few more lethal ingredients, starting with the long-fractured father-son relationship between Rusty and Nat, an intelligent but troubled 28-year-old battling family secrets new and old.

The most delightful return is that of Sandy Stern, the dapper, cunning attorney who helped Rusty beat murder charges the first time around. Sandy faces travails of his own: lung cancer.

“I am devastated for both our sakes,” Rusty says upon hearing Sandy’s diagnosis. “His damn cigars.”

Sandy takes the case anyway, assisted by his protégé, Marta, who also happens to be his daughter.

Another young woman, a former law clerk to Rusty named Anna Vostic, serves as the perfect example of a good person torn by past misdeeds. Racked with guilt and uncertainty, she must work through legal and moral ambiguity as the stakes are ratcheted up.

Tommy, beleaguered and buffeted by insecurity and the occasional, slight misstep, is the novel’s moral center. Exhausted by endless bureaucracy and shaky ethics on all sides of the legal system, he has found unexpected contentment as a first-time father late in life.

Unlike Rusty, marital fidelity poses no challenge for him. “The idea of cheating on his wife was incomprehensible to Tommy, literally beyond the compass of any desire. Why? What could be more precious than a wife’s love?”

“Innocent” unfolds from the perspective of the various participants in the case, allowing the burden of proof and the burden of guilt to share the stage. Turow is a shrewd observer of criminal-justice machinations, as well as the inextricable links between the courts, politics, and the media.

What puts him above the standard judge-and-jury roller-coaster rides lining so many bookshelves are his devastating accounts of regret and rumination in all of his characters. It is, to borrow from William Faulkner, the human heart in conflict with itself.

Adding that internal conflict to ambition, sorrow, and righteousness — with murder, adultery and careers at stake — makes for an easy summary judgment: “Innocent” is anything but a guilty pleasure, it’s prime popular fiction.

Erik Spanberg is a freelance writer in Charlotte, N.C.