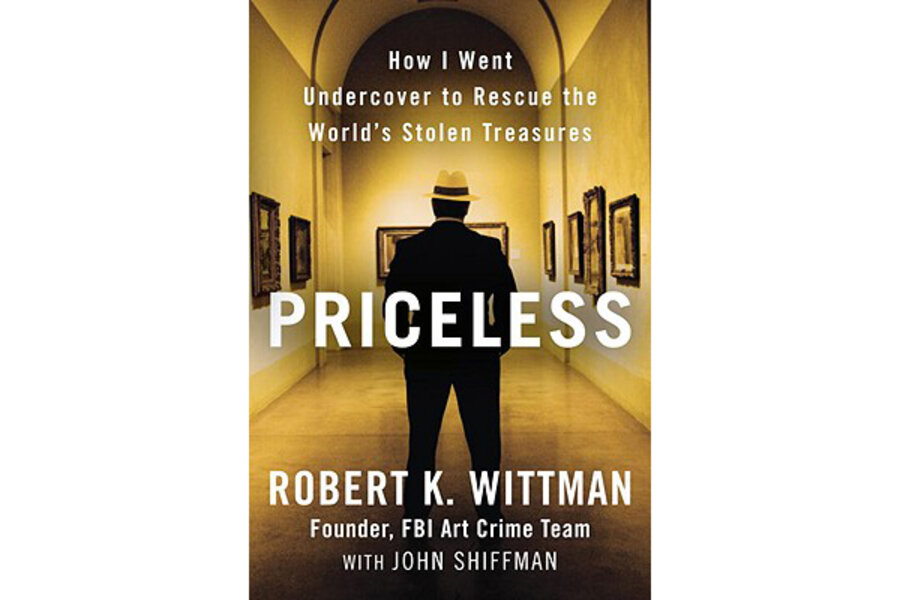

Priceless

Loading...

Writing about art theft, Robert K. Wittman – who founded the Federal Bureau of Investigation’s art crime team – paints a portrait of his former employer, and it isn’t a pretty one. In recent years, the bureau, along with the Central Intelligence Agency, has been criticized for valuing a lumbering and self-serving bureaucracy over results.

If there ever were an intriguing niche within the FBI, however, it would seem to be the one that Wittman carved out as the bureau’s chief investigator of international art thefts. But as Wittman details in his memoir Priceless (written with John Shiffman), the actual work is frustrating more often than it is glamorous.

As crimes go, art theft is especially sensitive because the stolen property is notoriously hard to sell, so the thieves eventually realize that the best option for them is to destroy it. Most stolen art is not recovered, and authorities speculate that much of the missing work ends up in a landfill somewhere. Such losses are almost uniquely wrenching in the annals of crime. Money can be reprinted, but once gone, a Monet is gone forever.

The son of an American airman and a Korean War bride, Wittman developed a crush on the FBI as a child when the family relocated to Baltimore. Young Bob heard the taunts leveled at his mother by locals at the same time that the bureau was beginning to emerge as a champion of civil rights. The idealistic Wittman joined up and soon found himself not only working art theft but also taking a year-long course, learning how to tell the difference between a Gauguin and a Cézanne and how to hold forth on palette, composition, and light.

Undercover agents not only have to talk the talk but do it with a certain amount of swagger, and Wittman excels here as well. Not that he ever dropped his guard: believing one should make as few changes as possible when constructing a fake identity, he changed his last name to “Clay” but kept his first, which worked out well when he picked up a crook at an airport once and ran into a neighbor who called out “Hi, Bob.”

Wittman’s biggest case involved the still-unsolved theft in 1990 of 13 works of art from the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum in Boston. The works included one of Vermeer’s 35 known paintings and several Rembrandts, including his only seascape, as well as a Manet and five Degas sketches. The total is valued at over $500 million, making the Gardner break-in not only the biggest art theft but also the biggest property theft in history.

“Priceless” begins and ends with the Gardner case, which Wittman worked on for years, flying tens of thousands of miles and meeting repeatedly with a cast of unsavory and possibly homicidal characters. Throughout, but especially near the end, when the art works seemed almost in reach, he was micromanaged and second-guessed at every turn. More than once, Wittman calls the FBI “a giant bureaucracy” and explains how cases are assigned where they occur, so that the Gardner affair ended up under the jurisdiction of the violent crime squad in Boston rather than Wittman’s art crime unit. This was a careermaking case for the Boston supervisor, of course, who resorted to such hamfisted tactics as inserting one of his own agents into a meeting with gangsters thrown off by the presence of a stranger. The Gardner case ends with a whimper, not a bang, and certainly not an arrest.

Wittman’s touch is light; he’s more a watercolorist than an oil painter. But his former employers (he has retired and now heads his own international art security firm) are not going to be happy with the way they’re portrayed in “Priceless.”

The gentlemanly qualities of the prose here may be due in part to the fact that the book is co-written, which means it has all the vices and the virtues of the as-told-to approach.

The style is bland; when Wittman is surrounded by gun-toting sociopaths who can barely speak English, he often sounds drowsy, like a guy watching a kids’ soccer game rather than someone who could lose his life at any moment. But co-author Shiffman is a master of the cliff-hanger ending, and each chapter concludes with a come-on that keeps you reading.

A more white-knuckle account of art theft and recovery is Edward Dolnick’s “The Rescue Artist: A True Story of Art, Thieves, and the Hunt for a Missing Masterpiece.” But if you want to build a case for FBI reform, Wittman’s story is priceless.

When not gazing in awe at the world’s masterpieces, David Kirby teaches English at Florida State University.