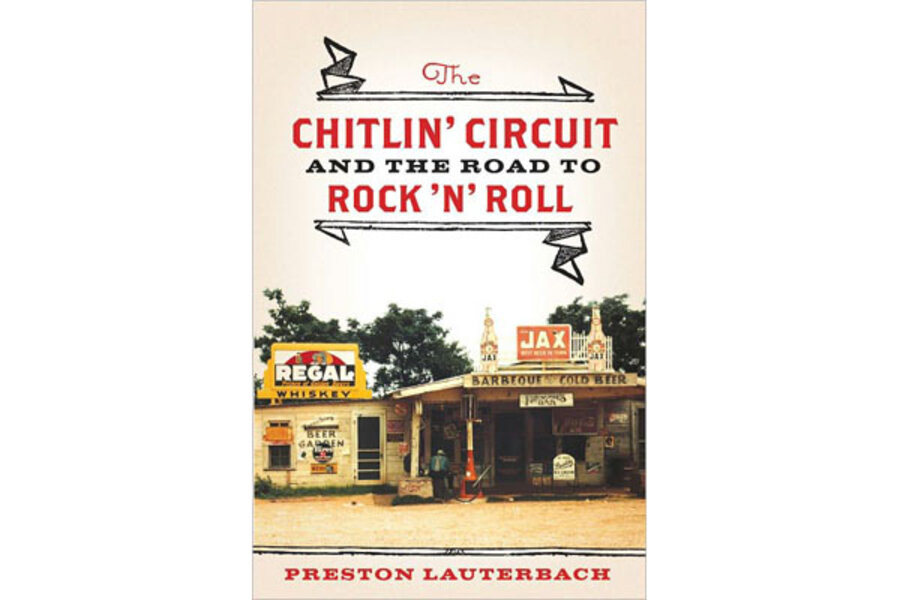

The Chitlin’ Circuit and the Road to Rock ‘n’ Roll, by Preston Lauterbach.

Loading...

It’s 1951, and a group of teenagers who call themselves the Kings of Rhythm are motoring up Highway 61 from the Mississippi Delta, their instruments tied to the top of the car. A 19-year-old named Ike Turner is driving, and he and the band are on their way to Memphis when they hit a bump that sends their equipment flying. Turner and the others hail from Clarksdale, where poor folks make instruments out of wire and broomsticks, so when they discover a fracture in their amplifier, they just patch it and shoulder on.

Multiply this scene a thousand times and you’d have the raw material for a documentary on the chitlin’ circuit, that string of venues where black entertainers not only made a decent living in a segregated time but also honed their chops and got ready to raise the curtain on a new sound called rock ‘n’ roll. A lot of musical biopics have told parts of the story by showing how artists as different as Ray Charles, Etta James, and Ike & Tina Turner went from one club to another, learning how to “dump house,” that is, turn the joint upside down with their seething rhythms and surefire stagecraft. No single film tells the whole story. Now, though, Preston Lauterbach’s The Chitlin’ Circuit: And the Road to Rock ‘n’ Roll – a fact-studded and exhaustively researched book – does.

The story begins with a musician and entrepreneur named Walter Barnes, a mover and shaker who crossed racial lines to buddy up with Al Capone, who taught him how to organize. In the Jazz Age, so-called territory bands played out of hotel ballrooms and broadcast over low-watt radio stations but also traveled as far as their reputations (and broadcasts) carried them. Barnes contacted dance-hall operators, promoters, colored-friendly hotels and restaurants, and took the territory band to a whole new level; like Capone’s Italian ancestors, he fused a bunch of separate city-states into a cohesive whole.

The key to the chitlin’ circuit was “the stroll,” the main thoroughfare of the black part of town, the street with the barber shops, dental clinics, drugstores, cab companies, restaurants, lodgings, and dance halls. In Monroe, La., that would have been Desiard Street; in Jacksonville, Fla., West Ashley Street; in Macon, Ga., Fifth Street; and in my home town of Tallahassee, the stroll would have been Macomb Street, where, when I came in 1969, the Red Bird Club was still in business.

Just before and during World War II, entertainers like Louis Jordan and the Tympany Five showed that a handful of musicians could make just as much noise as an entire orchestra. As men and resources went into the war effort, Jordan became the model for every black pop group from Little Richard and Fats Domino to B. B. King and James Brown. These entertainers roughed up Jordan’s svelte style as swing became rhythm ‘n’ blues and the word “rock” began to appear in one form or another in song lyrics, like Roy Brown’s 1947 “Good Rockin’ Tonight,” as well as newspaper write-ups that described audiences as “rockin’” to the new sound.

As the music changed, the bands’ names did, too, and in a way that suggests the difference between the start of the chitlin’ circuit and its end. In the beginning, the road was ruled by Dittybo Hill and His Eleven Clouds of Joy; Herman Curtis and His Chocolate Vagabonds; Belton’s Society Syncopators; and Smiling Billy Stewart and His Celery City Serenaders. Later, these groups were replaced by the Chickenshackers; the Mighty Mighty Men; the Tempo Toppers; and the Famous Flames.

But even combos as macho-sounding as these couldn’t stand up to the forces of urban renewal. The federal Housing Act of 1949 meant that slums would be purchased so that civic blight could be replaced with vibrancy. At least that was the idea; what this often meant in practical terms was that functioning black neighborhoods were replaced with high-rise projects that quickly turned into crime factories. And following the 1956 Federal Aid Highway Act, even more black-owned homes and businesses gave ground to the first interstate highways, and the chitlin’ circuit effectively disappeared.

In Tallahassee, the Red Bird Club has long since vanished; where once stood a ramshackle wooden building that churned out rhythm ‘n’ blues is now a foreign car repair shop that services Mercedes Benzes and Porsches. But I’ve heard that Duke Ellington played there when the chitlin’ circuit was young, and it’s a fact that, just before it passed into history, Ray Charles played at the Red Bird as well. You can pull the building down board by board, but the music? That’s indestructible.

David Kirby is the author of “Little Richard: The Birth of Rock ‘n’ Roll.”