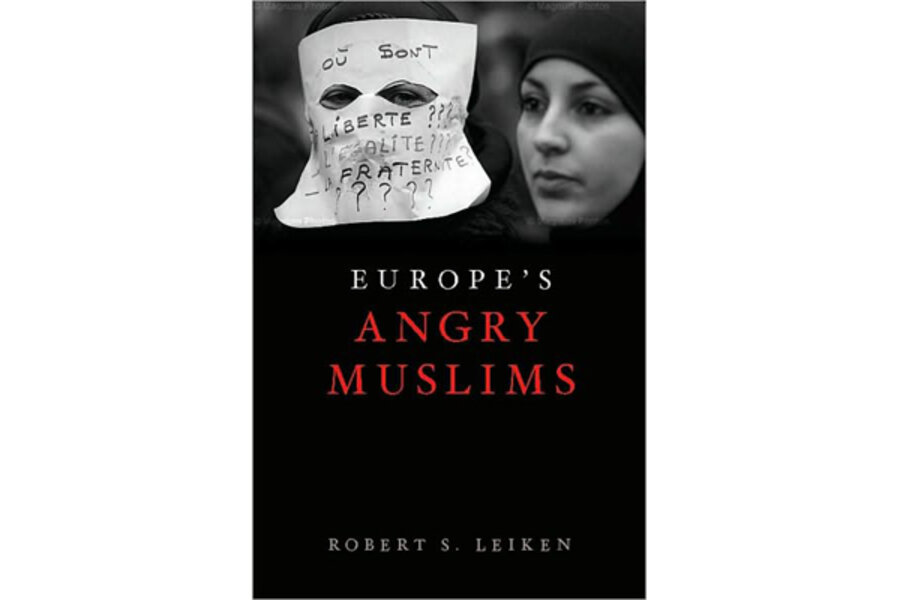

Europe's Angry Muslims

Loading...

Ever since September 11, 2001, Americans have become more interested than ever before in learning about those who use their Muslim religious training to justify deadly attacks.

Robert S. Leiken has been researching potential Muslim aggressors in the wake of 9/11, concerned about vulnerability within the United States but focusing mostly on England, France, and Germany, hoping to learn what knowledge might be transferable. Leiken is an unusual scholar, a mixture of PhD academic, think tank independent, community organizer, and immersion journalist. The result is a book with much to teach about Muslim men and women who have settled in three European countries as well as the US. The book will almost surely infuriate some readers because Leiken refuses to demonize a religious community in toto. But it might infuriate other readers because in some chapters Leiken seems to rely on stereotypes while trying to lead a nuanced discussion. Perhaps the most appropriate caveat is this: While learning about new worlds from Leiken’s research, beware the unexpected turns; Europe’s Angry Muslims is a troubling book to consume, for many reasons.

In carefully crafted chapters, Leiken writes that more-or-less repressive government policies aimed at Muslim populations in France appear to have minimized deadly violence; that more tolerant government policies in England have allowed an overabundance of deadly violence; and that Germany might become a greater trouble zone than it is currently, especially because of Muslim populations with national origins in Turkey.

If that summary makes Leiken sound like a reflexive law-and-order authoritarian, well, his words do sometimes come across that way. But there is nothing reflexive about Leiken’s thought process. He is a wide-ranging, freethinking scholar now past age 70 who lets his conclusions fall where they may, apparently without regard to intellectual trendiness or easily labeled political ideology.

The subtitle of the book explains a great deal about Leiken’s original scholarship, with the term “second generation” serving as the key. In England, France, Germany – and to some extent the United States – the potential and actual jihadists are the children of the original immigrants from Pakistan or Turkey or Algeria or other nation-states with concentrated populations of Muslims. Those second-generation residents (sometimes legalized citizens of their adopted countries, sometimes not) often feel unfairly treated in the job market, in school, in society at large. As a result, they convert that feeling of dispossession into violent plans.

An example of that violence occurred in London on July 7, 2005, when bombers at four sites killed 52 train and bus commuters during the morning rush hour, injuring another 700 or so, and disabling the transportation system and the mobile telecommunications infrastructure. The perpetrators became known as the Beeston Bombers, Beeston referring to an urban enclave in metropolitan Leeds, England, about three hours north of London by train. With his characteristic thirst for textured knowledge, Leiken learns how thousands of Pakistani nationals from the district of Mirpur ended up in Beeston, and how the transplanting of their culture to a foreign nation apparently spawned some deadly bombers.

Because Leiken’s book is so difficult to summarize meaningfully in a review assigned at 750 words, it seems wise to quote Leiken directly at the end, giving readers an opportunity to become acquainted with his manner. The quotation comes from the end of a chapter on Muslim-based violence in Germany:

“Germany had joined the United States as a target of what we might call strategic jihad, jihad with specific battlefield objectives, terror attacks linked to the Afghan/Pakistani war, retaliatory jihad to punish war enemies. Examples include the 2009 Fort Hood [Texas] massacre and the 2010 Times Square [New York City] bomb plot as well as other planned assaults on the United States for the Afghan war. They appear to be modeled on the jihadis’ most successful attack from a strategic standpoint – the Madrid bombings. If that is the case, Germany looms as a particularly vulnerable target. It is the most fragile NATO ally, one with a large alienated Muslim second generation that is particularly susceptible to the Taliban and al Qaeda’s Turkic allies in a country deeply divided not only over immigration and terrorism but even over its own raison d’etre. If France is the past of European jihad, and Britain is its present, Germany could be its future.”

Steve Weinberg is a member of the National Book Critics Circle.