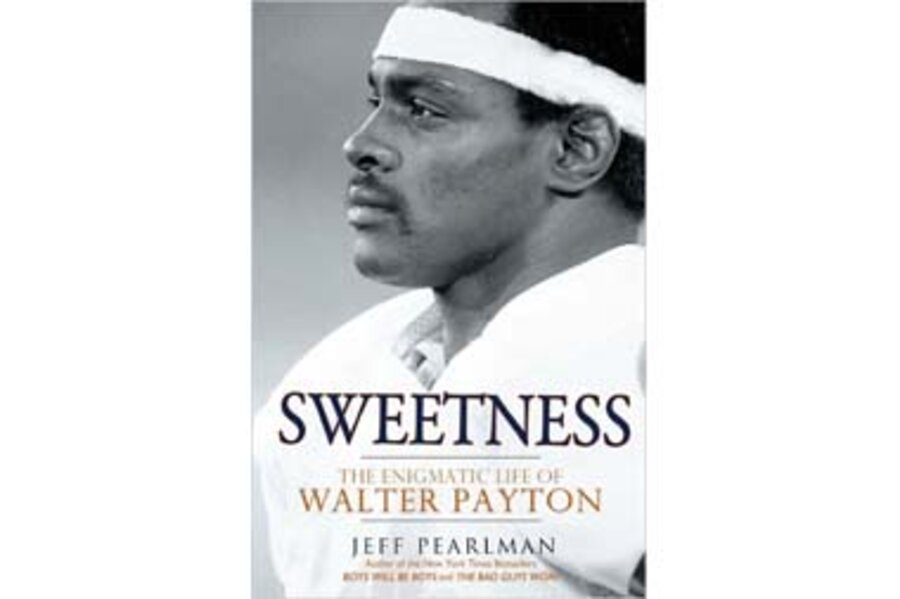

Sweetness: The Enigmatic Life of Walter Payton

Loading...

One of the most telling anecdotes in Super Bowl history involves Walter Payton, who was the heart and soul of the Chicago Bears for many years.

After 10 mostly futile seasons toiling for the franchise, the punishing running back finally could call himself a champion after Super Bowl XX in 1986.

The Bears had just shellacked the New England Patriots, 46-10, in the Super Bowl’s most lopsided victory to that point. But in the joyous aftermath in the New Orleans Superdome, Payton went missing. Instead of celebrating with his teammates in the Chicago locker room, he had retreated to a broom closet for a good cry – not of joy, but of disappointment.

Payton was heartbroken. On the sport’s biggest stage he not only hadn’t scored a touchdown, but when Chicago had a short-and-goal opportunity late in the third quarter, a hulking rookie defensive lineman, William “The Refrigerator” Perry, was sent into the game to carry the ball the last yard into the end zone. It was a whimsical, gimmicky moment that would forever prevent Payton’s name from appearing in the game’s scoring summary.

It took his angry agent to read him the riot act and force him to return to the locker room and put on a good face. Anything less, he warned, would ruin Payton’s good-guy image and paint him as a selfish moper.

This is just one of the windows on the inner Payton that Jeff Pearlman offers in his nearly 500-page biography of the Hall of Famer, Sweetness: The Enigmatic Life of Walter Payton. It stands as one of the most engaging, thoroughly researched, and frank football books imaginable.

As a powerful, well-told, and tragic story, it ranks alongside Jane Leavey’s 2010 blockbuster about Mickey Mantle, “The Last Boy.”

One irony here is Mike Ditka’s reaction to Pearlman’s “tell it like is” profile of Payton. The Bears’ former coach said if he met the author, he would spit in his eye for revealing so much of the seamier side of Payton’s life after his death, including his marital infidelities and suicidal thoughts. This was without reading the book, and by the coach who’d missed the opportunity to call Payton’s number, not the Fridge’s, in the Super Bowl.

Pearlman claims his portrait of Payton is not meant to be exploitative, and that the 678 interviews he conducted were a reflection of his desire to tell a fascinating life story well. The end result: He came to love Payton, not for his insecurities and shortcomings, but for his sheer humanity. “I love what he overcame, I love what he accomplished, I love what he symbolized, and I love the nooks and crannies and complexities,” Pearlman concludes in the book’s final paragraph.

Pearlman only interviewed Payton once, in 1999, as a reporter for Sports Illustrated, when Payton was so ill and frail that Pearlman strained to recognize pro football’s reigning all-time rushing leader. He died later that year at age 45, a gut-punch to the fans who came to know “Sweetness” as one of the most genuinely friendly stars in the game. He understood celebrity and embraced its demands, going beyond mere autograph-signing to introduce himself to people on the street with a warm, “Hi, I’m Walter – Walter Payton.”

He had a reputation for being kind-hearted and caring and knew the names of ballboys and team interns – and even where they went to school. The NFL has honored his memory by naming its annual player community service award the Walter Payton Man of the Year Award.

The “Sweetness” nickname, interestingly, stemmed not from his outwardly sunny and playful personality, but from something that occurred during a practice for a college all-star team. While eluding a would-be tackler, he yelled out to the defender, “Your sweetness is your weakness!”

Payton was incredibly determined to overcome any doubts about his ability, and used the humiliating first game of his pro career, when he gained zero yards, as a motivation thereafter. He trained hard, making countless runs up a steep, treacherous hill near his home during the offseason. He didn’t shrug off losses, either, and initially refused to participate with teammates in taping “The Super Bowl Shuffle” video in 1985 after Chicago was handed a rare regular-season loss. He later was taped against a blue screen and his image spliced into the smash-hit, rap song project, a natural for a guy who had once been a finalist in the national “Soul Train” dance competition while in college.

What happened to the Super Bowl ring that Payton earned as a member of that ’85 championship team is a story symbolic of the frustrations the Bears’ star encountered in retirement.

To meet his community service requirement for speeding violations, Payton became a volunteer for a high school basketball team in Hoffman Estates, Ill. After a pep talk about commitment and trust, he handed a dumbstruck Nick Abruzzo his Super Bowl ring and told him to keep it for the weekend. “I trust you, just like you need to trust one another,” he said.

Abruzzo held a party at his house and in handing the ring around it was lost. When he reported back with the jarring news, Payton managed to tell him, “Don’t worry, it will turn up.”

It did, but not until several years later, when it was found by a fellow Hoffman Estates athlete and major Payton fan who had moved the Abruzzos' discarded family couch to his college dwellings at Purdue University. One day, while his dog was trying to retrieve a chew toy caught in the couch’s underside, the young man reached underneath and felt the ring.

It was returned, but to Payton’s estranged widow.

Ross Atkin is a sports writer for the Monitor.