Island of Vice

During Theodore Roosevelt's contentious two-year term as New York City police commissioner, he headed a divided four-man board that also included Colonel Frederick Grant, son of former president Ulysses. Sometime after Roosevelt's righteous crusade to eradicate vice had alienated much of Gotham's citizenry, the New York Mercury newspaper sided with Grant on an intra-board squabble, calling him "the noblest type of man like his father, Ulysses" and adding for good measure that "no Roosevelt was ever President; no Roosevelt ever led an army to victory – and none ever will."

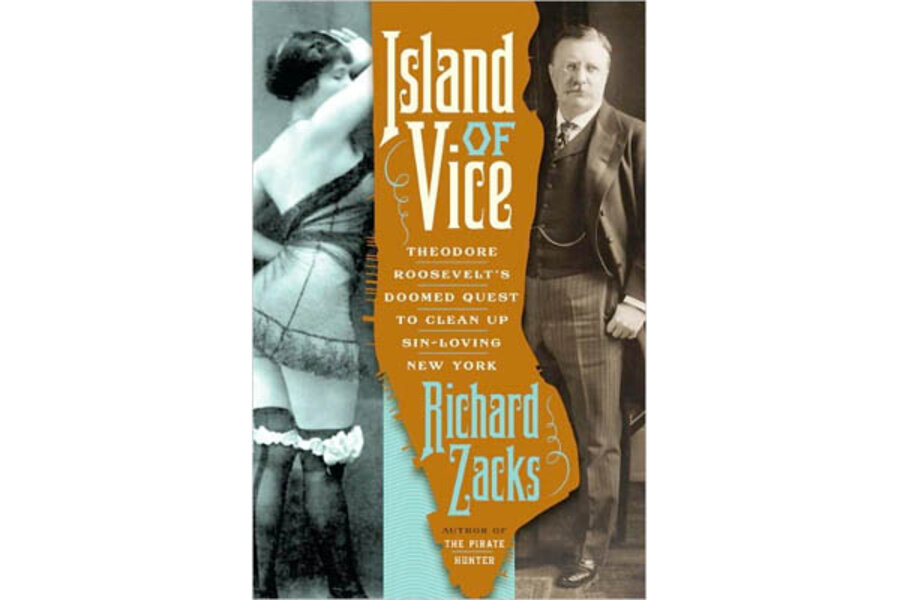

Grant fils is now forgotten, while T.R., of course, went on to achieve the rank of colonel himself, leading his Rough Riders in the Spanish-American War, before becoming the 26th president of the United States. Part of the pleasure of Richard Zacks' Island of Vice: Theodore Roosevelt's Doomed Quest to Clean Up Sin-Loving New York is in knowing how the story ends – that the stubborn, imperious young city official trying to reform Tammany-era New York would achieve greatness throughout his larger-than-life career. The book holds other pleasures, too: it's a lively and often entertaining portrayal of urban life at the close of the 19th century. But it occasionally gets bogged down in details of little interest, even with a figure as compelling as Roosevelt at the center of the action.

In the 1890s, New York "reigned as the vice capital of the United States, dangling more opportunities for prostitution, gambling, and all-night drinking" than any other American city, explains Zacks, author of "History Laid Bare" and "The Pirate Hunter," at the outset. The Democratic Party's corrupt Tammany Hall political machine had run the city since the 1860s, and the police force made no attempt to curb crime of a victimless nature. When Reverend Charles H. Parkhurst took to his pulpit one Sunday in 1892 and denounced the mayor and the police as "a lying, perjured, rum-soaked and libidinous lot," he wasn't entirely off the mark: in the seediest precincts, the police not only tolerated but regulated vice, demanding stiff payments from brothel and saloon owners who hoped to stay in business and even settling turf wars among criminals.

Parkhurst's campaign led to a state probe of the police force, and its astounding findings about the breadth of corruption helped pave the way for a Republican victory in the 1894 election. When Roosevelt was appointed police commissioner by the new mayor, William Strong, he was met with an immense amount of goodwill by the city's people and press. He almost immediately squandered it by deciding that his first major reform initiative would be enforcing the city's Sabbath laws, which required saloons to be closed on Sundays. Roosevelt, Zacks writes, framed his crusade as a fight "against selective enforcement of the law," but in New York, a city of heavy drinkers, his diligence didn't go down easy. Worse yet, Roosevelt declared that Sunday began at precisely 12:01 a.m.

Because loopholes in the law allowed hotel guests or members of private clubs to drink on the Sabbath, "the heart of the Sunday crackdown fell along class lines." While, in a preview of Prohibition, people found imaginative ways to drink their beer seven days a week, the New York newspapers still pilloried the commissioner. "To show the absurdity of Roosevelt's doctrinaire enforcement of all laws," they "delighted in unearthing every dead-letter law imaginable," including those prohibiting flying kites south of Fourteenth Street and placing flowerpots on windowsills. The unbending Roosevelt responded by cracking down further, expanding his reform efforts to prostitution and gambling, and he chafed when the papers suggested that dangerous criminals were flocking to New York City because the police were tied up with the enforcement of vice laws.

The focus of Zacks's narrative eventually shifts from the fascinating vice crusade to what even the police chief who reported to Roosevelt's board, complaining to a reporter, called its "petty quarrels" and "constant bickerings." Most of these were procedural disputes having to do with promotions in the Police Department, part of Roosevelt's efforts to advance the worthiest officers while weeding out the most corrupt. The book would have been better served by condensing the sections on these bureaucratic proceedings, but doing so might not have come naturally to Zacks, an exhaustive researcher who's thorough to a fault throughout the book. (This author doesn't merely note that the mild weather on an Election Day encouraged turnout: he further elaborates that "the front-page 'Weather Prediction' called for 'fair and warmer,' with few clouds and mild southwesterly breezes.") To his credit, Zacks is such a vivid writer – his description of Roosevelt advisor Elihu Root as "waggle-eared, with a push-broom mustache over a weak chin" is typical of his evocative prose – that he manages to breathe some life into even the most tedious workings of municipal government.

Roosevelt's anti-vice campaign brought him national attention, and during his brief tenure as police commissioner he was more popular outside of New York than in it. After the 1895 election, T.R. was recognized for effectively using the police force to prevent the voter fraud rampant during the Tammany days. But his "purity crusade" was blamed for the widespread Tammany gains and Republican losses of that election, and Roosevelt, realizing that his days as commissioner were numbered, began currying favor with likely Republican presidential nominee William McKinley. After T.R.'s two years at the job, Zacks notes, "Despite one of the most concerted efforts in the history of New York City to crack down on whoring, gambling, and after-hours drinking ... all three somehow thrived." By the time President McKinley appointed Roosevelt assistant secretary of the navy in 1897, most New Yorkers were thrilled to be rid of him.

Barbara Spindel has covered books for Time Out New York, Newsweek.com, Details, and Spin. She holds a PhD in American Studies.