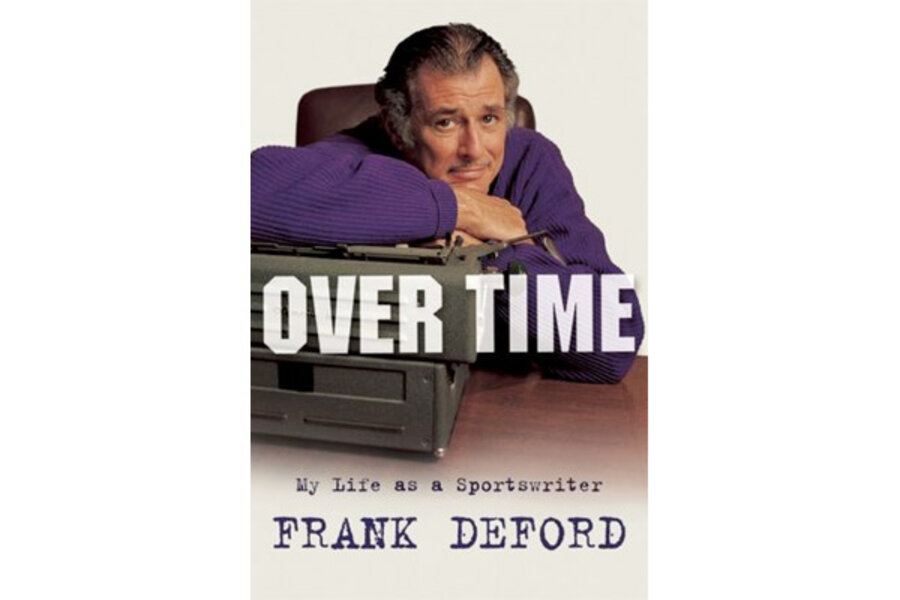

Over Time

Loading...

"Soccer is the coitus interruptus of sports." Ah…Frank Deford, the justly celebrated sportswriter from whose keyboard drop sparkling aperçus like so much ripe fruit. Consider, too, that other game of football: "Football players love coaches who are mean to them, because, I suppose, you've got to be mean to play football."

Salty opinions -- "Big-time college sports is, of course, a complete fraud, a fountain of deceit" -- come by the bushel-load in Over Time, Deford's new memoir, which captures his polished crustiness. He writes with brio, dash, and without pretension (he complains that nobody spells his name correctly, so he misspells it DeFord as a running joke throughout the book); when he harks back to a better time, he doesn't sound like a fogy or a snob, but beguilingly evocative.

His family had lost their sizable bankroll by the time Frank came along in 1938. It didn't matter; they were happy. He grew up in a Baltimore that was no longer a cosmopolitan jewel, the gateway to Dixie, but "a tentative place only a stream of two short of a backwater" that, still, left an important mark: "I was raised -- infused -- with a distaste for the smug and the high-hat." He found employment -- he sought employment -- at Time-Life's most déclassé, sweaty, financially calamitous ragamuffin: Sports Illustrated.

Thus, excepting the bed of ivy he slept in at Princeton, Deford's home was in the bush. But this was good, for in the bush were stories worth telling. When he started in the sportswriting business, if it wasn't baseball, boxing, or horse racing, with a little golf, track and field, and the occasional Olympic blip, "all else was, well…bush," everything that didn't meet the standards of "the approved athletic ecclesiastical calendar/atlas. There were bush towns, of course, and bush events and bush promoters and bush leagues. If any American sportswriter had ever bothered to go to the World Cup, it would surely have been labeled as bush. So too the countries where it was played. Bush countries."

Deford country, then. "I looked for what was real and unusual, athletic quaint": soapbox derbies, thrill-car rodeos, big-truck racing, alligator wrestling, waterskiing, cheerleading contests. He wrote about pro basketball when it was bush yet boasted Wilt Chamberlain, Bill Russell, Elgin Baylor, and Deford's early find, Bill Bradley. He covered hockey and introduced us to Bobby Orr, "the Canadian Christ ice child," who lifted the bush Bruins to higher ground when "Boston was fed up with the Sawx…They were losahs. The Patriots were bush…and the Celtics had too many black guys." Ah, Boston...ah well. Tennis is one of Deford's favorite (then bush) sports, and his friendship with Arthur Ashe allowed him to elementally experience Ashe's breaking the color line in apartheid-era South Africa.

As much as the bush had Deford in its gravitational field, he also felt the pull of difficult sports figures, people like Jimmy Connors, Bobby Knight, and Billy Martin. "These are the best characters to write about, largely because so many people flat out don't like them…so it's a challenge to surprise or even upset the reader with the unexpected." Spare him the young, preening bloviators -- "the highest percentage, it seems, being wide receivers in football" -- and point him toward the people with some mileage on them, the old coaches, say, "because they've lived longer, more complicated lives. They're simply better stories."

The sports pages have been a nursery and a parish of terrific writing: Red Smith and Jimmy Cannon, yes, but also Ring Lardner, Westbrook Pegler, Damon Runyon, Paul Gallico, and James Reston, who all cut their teeth in the sports section. Deford sits comfortably in that company, summoning the poetry and rapture -- if he never spoke of it as such -- modern but also conversant with "before television and big money, when a great deal of sports meant hustling and scuffling, when there was a vagabond spirit."

"Of course, I'm old and cranky, so pay me no mind." Sorry, Frank: we're listening.

Peter Lewis is the director of the American Geographical Society in New York City.