Vita Nova

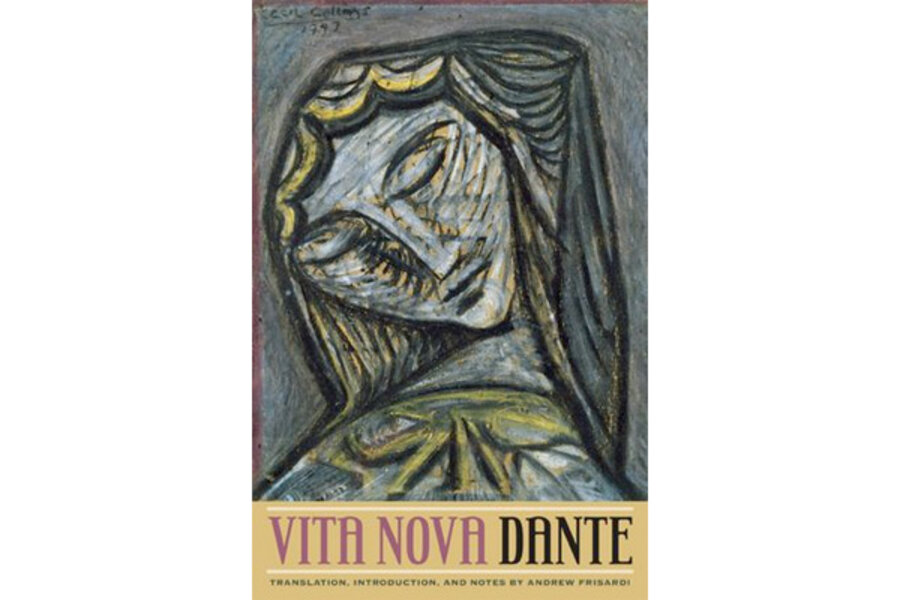

"In the book of my memory – the part of it before which not much is legible – there is the heading Incipit vita nova." "A new life begins": with this phrase, Dante Alighieri launches the tale of romantic rapture, spiritual growth, and poetic education that is his Vita Nova. This short but complex book, Dante's greatest work before "The Divine Comedy," has been freshly translated by Andrew Frisardi for a rich new edition (Northwestern University Press).

The catalyst of Dante's new life, which began at the precocious age of nine, was his first vision of Beatrice, a girl just a little younger than he was, wearing a "dignified" crimson dress. At the moment he saw her, Dante writes, he heard three messages from deep in his own body. "Here is a god stronger than I, who comes to rule me," said his heart; "Your beatitude has now appeared," said his brain; while his stomach lamented, "What misery, since from now on I will often be blocked in my digestion!"

This mixture of the romantic, spiritual, and bodily dimensions of love marks the "Vita Nova" as the product of a time very different from our own. Where today a young man might speak of falling in love, or simply feeling desire for a woman, to Dante the encounter with Beatrice is an ascent on the ladder of love that Plato described: it begins with the body and ends as a divine vision. Literally so, in Dante's case: as any reader of "The Divine Comedy" will remember, Beatrice resurfaces in that poem as Dante's guide to Paradise. This emphasis on the philosophical and spiritual rigors of love is what sets Dante apart from Petrarch, whose adoration of Laura belongs to the same medieval romantic tradition.

"Vita Nova" (Frisardi's preferred spelling; often it appears as "Nuova"), which Dante wrote in the 1290s when he was around 30 years old, presents a special challenge to translators, since it interleaves prose and verse in an unusual fashion. The prose narrative is devoted to the episodes in Dante's one-sided relationship with Beatrice – he went to great lengths to conceal his love from her, though from the age of 18, he tells us, he thought about little else.

Embedded in this story are poems Dante wrote at various points in his early career, all of which he insists were inspired by Beatrice – sonnets and ballatas in the dolce stil novo, the "sweet new style," that Dante helped to perfect. Frisardi handles both prose and verse deftly, bringing out the syntactic complexity of Dante's poems while still communicating their elaborate rhyme schemes:

Tell her: "My lady, this one's heart has stayed

so true and undeterred,

to serve you each thought pressed him with its seal:

from his first years he was yours; he's never strayed."

If she won't take you at your word,

tell her: "Ask Love, who knows the truth for real."

And finally present this meek appeal:

that if I've bored her with my alibi,

she tell me through an envoy I should die,

and I'll obey – a servant's paragon.

In addition to rendering the text into clear, nimble English, Frisardi supplies it with extremely thorough notes and a useful introduction, making his "Vita Nova" an excellent choice for readers new to the book, as well as for scholars.

Adam Kirsch is a senior editor at The New Republic and a columnist for Nextbook.org. He is the author of Why Trilling Matters, Benjamin Disraeli, and The Modern Element: Essays on Contemporary Poetry.