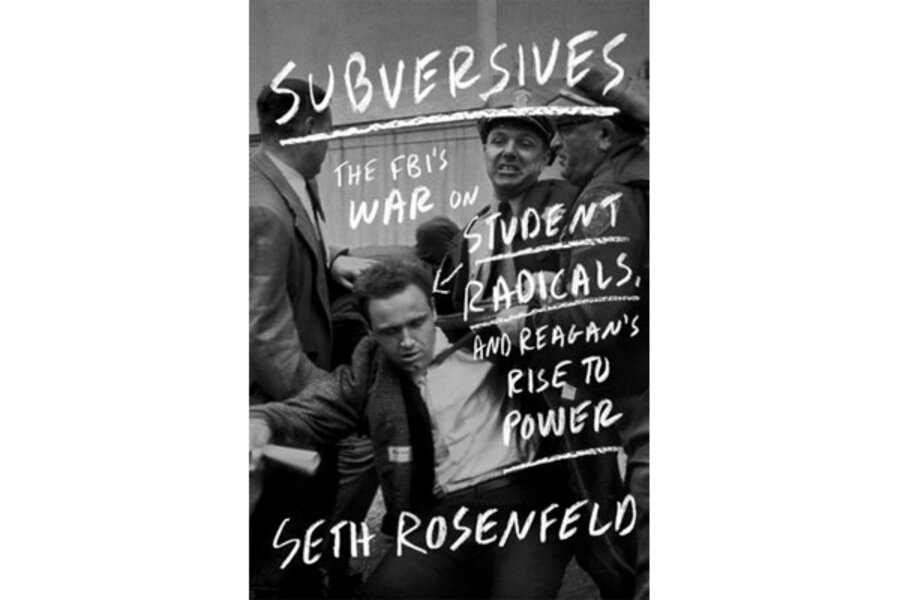

Subversives

Loading...

In case you’ve forgotten or are too young to know, the 1960s were the template for today’s political divisiveness. In Subversives, Seth Rosenfeld chronicles how the abyss formed. His book is crucial history. It’s also a warning.

In this work about unrest at the University of California Berkeley, Rosenfeld tells the stories of the frail, impassioned student leader Mario Savio; the measured but liberal Berkeley president Clark Kerr; and Ronald Reagan, the B-actor who, with the secret help of FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover, polished the conspiratorially based law-and-order message he formulated in the ‘40s as the rabidly anti-Communist head of the Screen Actors Guild to become governor of California in 1966.

Reagan is a hero to today’s GOP, which regards him as sunny, even moderate, but the way he handled unrest at UC Berkeley was cunning, vindictive, and excessive. Rosenfeld’s interviews with participants in student uprisings at Berkeley in the ‘60s and with Reagan’s associates depict this avuncular icon as ready and all too eager to crush dissent in the name of protecting American values.

A former investigative reporter for the San Francisco Chronicle, Rosenfeld spent decades accumulating this material, filing Freedom of Information Act requests that prompted the FBI to spend more than $1 million beating back his demands until it grudgingly released more than 250,000 pages of files. Rosenfeld has an agenda in this book of patience and passion: setting straight a previously hidden – and consequential – record. The way his stories converge evokes “They Marched Into Sunlight,” David Maraniss’ similarly structured 2003 book about a Vietnam War firefight.

Through FBI documents and interviews with players including Reagan right-hand man Edwin Meese III, Richard Masato Aoki (a FBI informer who also may have been a student radical), and protestors, Rosenfeld paints a chilling picture. Law enforcement organizations in Reagan’s California joined in a systematic attempt to smear students and professors, infiltrate their associations with moles, discredit the intellectual enterprise, and instigate actions designed to justify deployment of organizations spanning local police and the National Guard.

All came to a head in People’s Park, “where – six months before the violence at Altamont and a year before the killings at Kent State – the end of the sixties would begin.” People’s Park was a university-owned parcel UC Berkeley wanted to develop as a soccer field. But city residents and students resisted, instead seeking a “park to be a cultural, political freakout and rap center for the Western world,” according to the April 18, 1969 Berkeley Barb.

That May 15, Reagan had what Rosenfeld calls a “showdown,” setting law against demonstrators. By the end of the day, at least 169 people had been injured; no officer had been shot or seriously hurt, but more than 58 civilians were, 51 by police birdshot – or buckshot, which killed San Jose laborer James Rector and blinded Berkeley carpenter Alan Blanchard. Reagan put Berkeley under martial law.

Subsequent probes by state authorities and President Richard Nixon’s Justice Department absolved Reagan of responsibility for the tragedy. “The police didn’t kill the young man.... He was killed by the first college administrator who said some time ago it was all right to break the laws in the name of dissent,” Reagan told a Republican fundraiser a week after the incident.

The People’s Park chapter is the climax of “Subversives,” a book bristling with information. Rosenfeld also reveals Hoover’s role in covering up the friendship of Reagan’s son, Michael, with the son of mobster Joe Bonanno; the FBI chief’s hiding of details about his daughter Maureen’s love life; the way California’s informer-ridden, right-wing media built support for Reagan against incumbent Governor Edward Brown; and Reagan's character assassination of Clark Kerr, perhaps the most complex figure in the book. Kerr continued an academic career after being fired as UC Berkeley president in 1967. Kerr died in 2003 at 92. Hounded by Hoover, Savio is the book’s troubled lighting rod. He died in 1996. He was 53.

Hoover died in 1972 at 77, Reagan in 2004. He was 93.

In his Appendix, Rosenfeld says files he pried loose “show that during the Cold War, FBI officials sought to change the course of history by secretly interceding in events, manipulating public opinion, and taking sides in partisan politics. The bureau’s efforts, decades later, to improperly withhold information about those activities under the FOIA ate, in effect, another attempt to shape history, this time by obscuring the past.”

Profound thanks to Seth Rosenfeld for outing the truth and speaking truth to power.

Cleveland freelance writer Carlo Wolff lived in Berkeley and Oakland in the summer and fall of 1965.