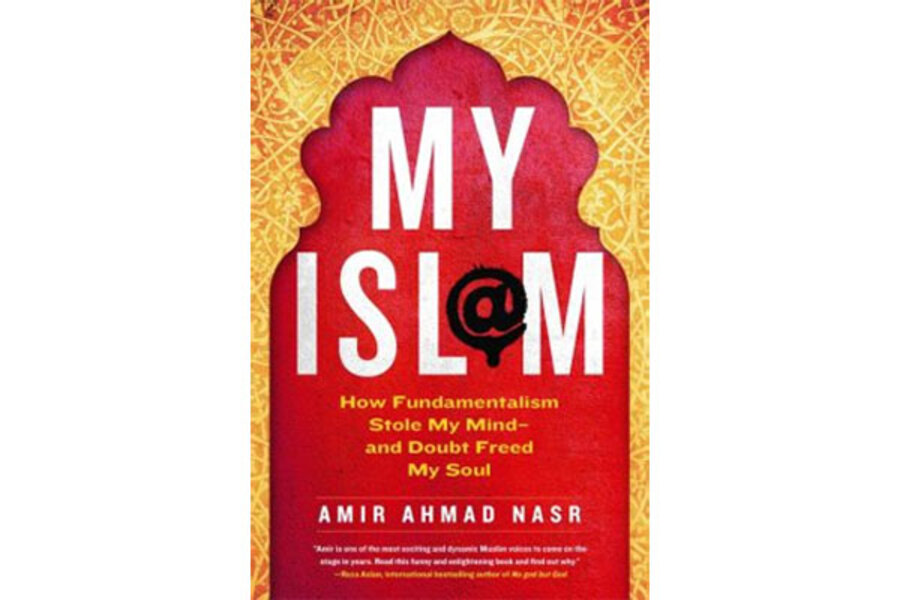

My Isl@m

Loading...

The heart and soul of Amir Ahmad Nasr’s My Isl@m? The Internet.

Typically considered by Western audiences a source of radicalization in Islamic circles – think terrorist forums, online calls to jihad, recipes for homemade explosives – the Internet takes a star turn here as liberator, as both a personal agent of awakening for Afro-Arab blogger Nasr, and an incubator of change in a Muslim world roiled by revolution. Nasr’s journey in “My Isl@m” is a testament to his prediction: that the Internet will be for Islam what the printing press was for Christianity – a driving force for reform.

Born in Khartoum, Sudan, and raised in Qatar and Malaysia, Nasr enjoys a relatively orthodox upbringing: praying five times a day, shunning the lewd programming of MTV, and in school, listening to his teachers rail against the infidel twin enemies, the USA and Israel. Bored by his IT classes in a sleepy Malaysian university town, Nasr stumbles upon the work of liberal Egyptian blogger “The Big Pharoah.”

“It was through him that I fell down the rabbit hole and landed in a virtual wonderland,” writes Nasr of the Arab blogosphere, a realm where nothing was taboo and the self-described “third culture kid” straddling multiple cultural identities finally felt he belonged.

Finding no other Sudanese bloggers, Nasr begins his own blog in 2006, “The Sudanese Thinker,” and joins a community of like-minded Arab bloggers plumbing the issues churning the Muslim world, from the Danish cartoon controversy and the Israel-Palestine conflict to Wahhabism, suicide bombings, and the US abuses at the Abu Ghraib prison in Iraq. Known in his family as the child who “thinks too much,” Nasr rejoices in the intellectual freedom and the way the blogosphere unites Arabs and Muslims from disparate geographic regions and religious persuasions.

As he blogs and interacts with others in the Arab blogosphere however, Nasr begins to question the teachings of his orthodox upbringing, dissecting Islam as he knows it until his doubts about religion gradually grow into disbelief and Nasr divorces himself from “the suffocating, dark, stinking dungeons of subordinating dogmatism.”

His personal journey from the comforts of orthodox faith to doubt and disbelief are among the strengths of “My Isl@m.” His struggle to hold on to his faith is real and his pain at leaving is palpable, a bitter passage Nasr himself labors to understand and share with his readers, quoting Sudanese-born Emory University law professor Abdullahi An-Na’im, who said “If I don’t have freedom to disbelieve, I cannot believe.”

Yet his story falls flat, and Nasr loses readers – at least this one – when he delves into tedious philosophy lessons, explaining his explorations with metaphysics, mythology, and “the empirical claims of contemplatives.”

More disappointingly, the revolutions roiling the Arab world, which get top billing in the book’s promotional materials, are relegated to a single section toward the end of the book and read as mere regurgitations of media accounts. Most readers would surely prefer more of Nasr’s insight and analysis, especially considering his unique background, as well as his connections in the regions discussed.

On a personal front however, Nasr shines, breaking the suspense about the ultimate fate of his relationship with religion. Struggling to distance himself from an Islam of dogma to one of reason and compassion, he returns to faith during a trip to Turkey, land of the mystic poet Rumi, where Westernized wine-drinking Turks dine peacefully next to their traditional, hijab-clad countrymen.

In a tender moment, moved by the grandeur of the setting and the reverberating rhythmic chant of the Turkish imam who reminds him of his beloved childhood mosque, Nasr reaffirms his faith under the grand dome of the Sultan Ahmed Mosque, or Blue Mosque, in Istanbul, this time as a follower of the mystical Sufi practice.

“My Isl@m” illustrates the explosive power of the Internet among youth across the Muslim world, who through social media and online activism, are changing old social, religious, and political orders. As such, Nasr’s story is remarkable in that it mirrors the personal journeys of millions of youth across the region for whom the Internet has upended traditional notions of Islamic belief and political order, giving way to a Muslim world “reborn,” via revolutions personal and political.

Husna Haq is a Monitor correspondent.