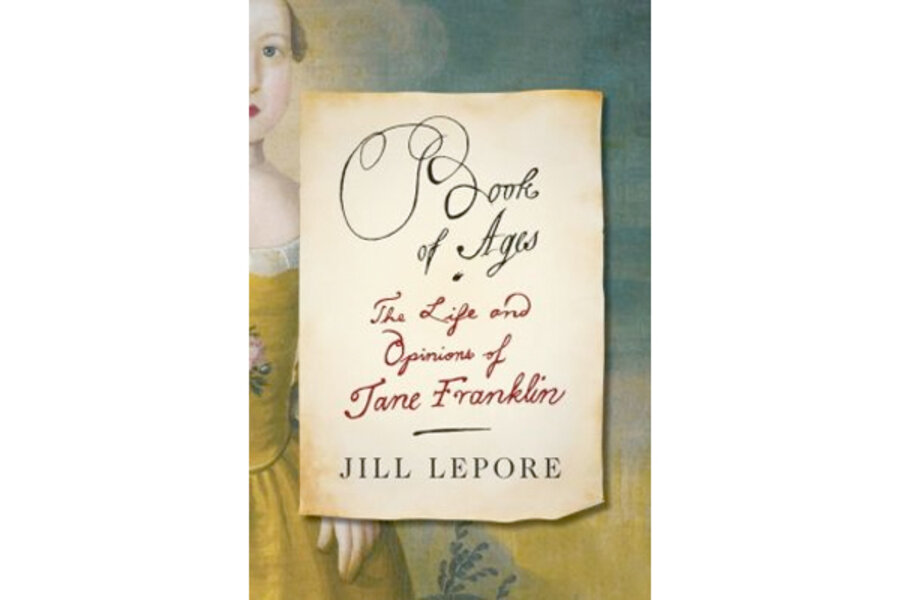

Book of Ages

In Book of Ages, historian and journalist Jill Lepore presents the extraordinary history of the ordinary, everyday life of Benjamin Franklin’s younger sister Jane. (She became Jane Franklin Mecom, after her marriage at age 15.) Jane lived the life that might have been Ben’s had he been a woman.

Using the shadows cast from Ben’s life and the comparatively few remains of Jane’s writing, Lepore describes Jane’s lively character and mind. “The facts of Jane Franklin’s life are hard to come by,” she writes. “If [Ben] meant to be Everyman, she is everyone else.” For Lepore, “[T]he story of a life like Franklin’s means very little unless it’s told alongside the story of a life like Jane’s.”

Jane’s brother lived in Philadelphia, London, and Paris, but she stayed in Boston. She had 12 children, only one of whom was alive when she died at 82. Her difficult husband had many problems, possibly including mental illness. Much of Jane’s life consisted of household labor, child care, running her own soap business, and an almost continual witnessing of the deaths of loved ones.

Yet she found time to indulge her love of books, including the Bible (she favored the Book of Job – he endured and tried not to complain!) and was a faithful Christian (unlike Ben who was a compulsive moralist but not traditionally religious).

She often went as long as a decade without seeing her famous brother but enjoyed a lively lifelong correspondence with him. (Ben wrote more letters to Jane than to any other correspondent.) “Jane’s letters are different than her brother’s – delightfully so,” notes Lepore. “He wrote polite letters. She wrote impolite ones.”

Ben was a little embarrassed by but enjoyed his sister’s natural way of putting things, and she could tease him and get her own in; he could outspell her but not outwit her. She was full of feelings and, in her older age, engagingly reflective and opinionated.

“She loved to walk up Copp’s Hill,” writes Lepore, quoting from Jane’s own correspondence. “ ‘I frequent go on the Hill for the sake of the Prospect & the walk,’ she wrote. She loved to look at the river, where a bridge was being built, connecting Boston to Cambridge. ‘It is Realy a charming Place,’ she wrote her brother.... Once, she even walked all the way across the bridge and into Cambridge. The Charles is wide. Crossing by foot from Boston to Cambridge is a very long walk for a woman of 74. ‘I sopose you wont allow it as grat a feeat as yr walking ten miles befor Breakfast,’ she wrote her brother, ‘but I am strongly Inclined to Alow it my self, all circumstances considered.’ ”

Lepore reminds us that some of Ben’s funniest and earliest pieces were written in something like her, Jane’s, voice: “When Jane Franklin was ten years old and her brother was sixteen, he broke out upon the literary stage disguised as a woman [Silence Dogood] whose girlhood had been spent reading books, and who refused to keep quiet.” Jane and Silence were gabby, witty, sharp-tongued observers of human hypocrisy.

While Ben – who clearly loved and appreciated his sister – is an important figure in “Book of Ages,” he is also the counterpoise to Jane in terms of the privilege and freedom he enjoyed as a man. Ben was so proud of having “broken through” despite all of his disadvantages and once wondered, “Who could have had a worst [sic] start?” Lepore answers: Jane did, simply because she was a woman. Given the opportunity, Jane herself might have been another Benjamin Franklin.

“Book of Ages” is an artful, serious, marvelous book. Lepore brings to it focus, intensity, and proud delight in her subject.

In the course of relating Jane’s life, Lepore never stops entertaining and informing us. Only after concluding the biography on page 267 does she offer evidence of her own difficult labor: 170 additional pages citing and explaining sources (so much “has been lost”) and appendicizing.

Lepore also credits historian Carl Van Doren, whose own 1950 book about Jane Franklin made almost no splash. But “Book of Ages” will make a splash, because Lepore has given us a history that reads with the intimacy of a novel. She has also demonstrated that there is no such thing as a “nobody” when it comes to the value we can derive from a life.

Bob Blaisdell is the editor of “Poor Richard’s Almanack and Other Writings by Benjamin Franklin,” published by Dover this month.