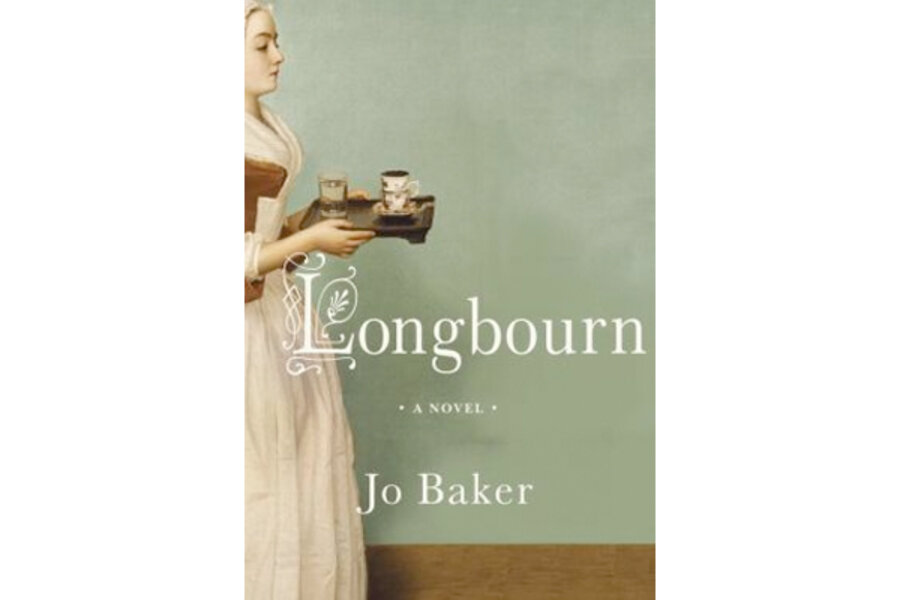

Longbourn

Loading...

It is a truth universally acknowledged by servants that a single man in possession of a good fortune makes for an enormous amount of extra work in a household filled with unmarried girls.

In fact, Mrs. Hill, the endlessly patient cook-housekeeper, nearly collapses on her mistress’s couch when Mrs. Bennet shares the good news in Jo Baker’s excellent fourth novel, Longbourn.

“A young, unmarried gentleman, newly arrived to the neighbourhood. It meant a flurry of excited giggly activity above stairs; it meant outings, entertainments, and a barrow-load of extra work for everyone below,” Hill thinks.

Next to Sherlock Holmes creator Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, it’s hard to think of any writer more imitated than Jane Austen. (In fact, I’ll let the Janeites and Sherlockians argue over which author stands atop the highest stack of copies.) While bitter experience has taught me to shy away from the endless romantic reduxes – including the detectives and especially the zombies – “Longbourn” offers something more substantial than a pale homage or a clever pastiche on “Pride & Prejudice.” In Sarah the housemaid, Baker has created a heroine, living in the same house as Elizabeth Bennet, who manages to shine despite Elizabeth’s long literary shadow.

While Baker includes Mr. Bingley’s arrival, the visit to Hunsford, and the Netherfield Ball, she does more than just revisit favorite scenes. She creates a vital downstairs version of one of the most beloved households in literature. Mr. and Mrs. Hill, the two maids, Sarah and Polly, and the coachman James rate just a mention in Austen’s classic, since, as good servants, they excel at disappearing. (It also wouldn’t have been genteel for a parson’s daughter to discuss such matters as dirty nappies, monthly rags, or chamberpots, even though somebody had to clean them.)

And someone had to get the girls ready for the Netherfield Ball and wait with the horses in the rain for the dancing to stop. And someone had to sit up past midnight, even though the work day began before 6 a.m., to let them in again and supply them with a fortifying late-night snack.

While Sarah helps Elizabeth and Jane into their dresses and arranges their hair, she can’t help feel like Cinderella, even though she considers herself a “wrung-out dishrag of a thing.” “She could not go to their ball, no more than she could attend a mermaids’ tea-party; but still she felt herself get blinky, her nose tickling.”

For Sarah, an orphan whose parents died of typhus, her most immediate concern isn’t whether Elizabeth marries Mr. Darcy; it’s whether she can get the mud out of that young lady’s hems.

“If Elizabeth had the washing of her own petticoats, Sarah often thought, she’d most likely be a sight more careful with them,” Baker writes.

That one sentence gives a sense of how Baker turns the tables in “Longbourn.” The work of managing the slightly run-down household – from the misery of wash day, which begins at a freezing 4:30 a.m., to the headache of coming up with a Family Dinner that will impress guests while giving the impression that the family dines that way every day – keeps all five servants occupied to the point of exhaustion.

Sarah, however, still finds time to be curious about James, who arrived out of nowhere and whom she finds irritatingly close-mouthed about his past. She’s also fascinated by Tol Bingley, the handsome black footman at Netherfield.

Overall, despite Mrs. Bennet’s flutterings and nerves, the Bennets and their daughters are relatively kindly employers. (Elizabeth loans Sarah her novels and gives her a dress for dances, and Sarah is free to browse in the library.) Overshadowing everything is a larger anxiety: The estate is entailed. Once Mr. Bennet dies, the cozy haven Mrs. Hill has created for her elderly husband, the two foundlings she rescued and trained, and the new coachman, who was all but starving when he arrived, will be gone.

“They were safe at Longbourn only while Mr Bennet’s heart kept ticking: beyond that, they were dependent entirely on this stranger’s will,” Baker writes of Mr. Collins, who is viewed in rather a different light by the anxious servants than the unimpressed daughters.

There are other heartaches besides. James’s safety depends on concealing his past career. Despite his flirtations with both Elizabeth and Lydia, Mr. Wickham still finds time to hang around the kitchen hoping to prey on little Polly. And, as in the Oscar-winning “Gosford Park,” Mrs. Hill hides her secrets behind the guise of servant so perfectly that Sarah and the others never even suspect they’re there.

With the huge popularity of “Downton Abbey,” also created by “Gosford” screenwriter Julian Fellowes, fans counting down the weeks until the fourth season begins could do far worse than while away the wait with “Longbourn.” The household isn’t nearly as grand, but Sarah can give Anna a run for her money in the small-but-growing category of housemaid as romantic heroine, James is just as self-sacrificingly noble as Bates, and Mrs. Hill is every bit the warmhearted equal of Mrs. Hughes. Best of all, there are no incredulity-straining plot twists necessitated by actors’ contracts.

Yvonne Zipp is the Monitor's fiction critic.