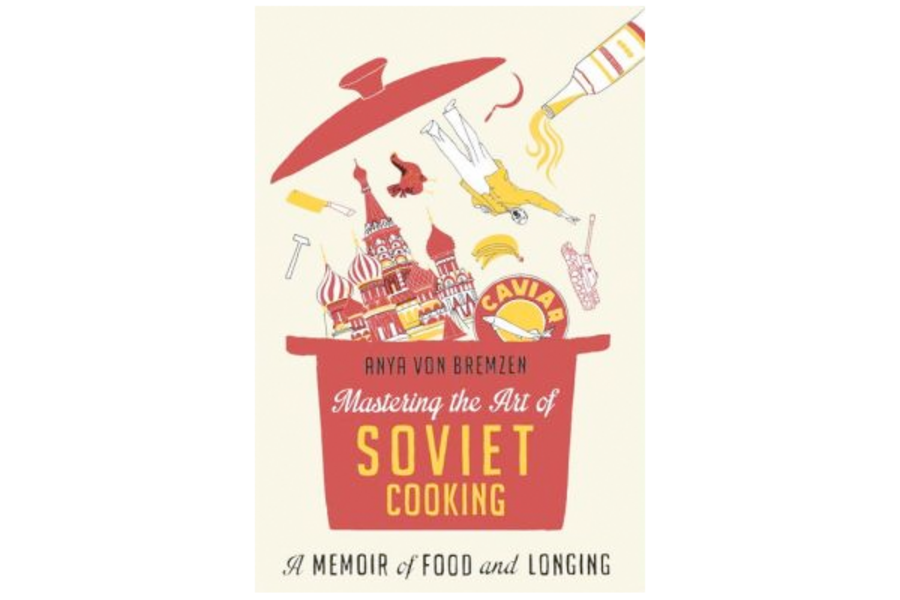

Mastering the Art of Soviet Cooking

Loading...

The prize-winning cookbook author Anya Von Bremzen was born in Moscow in 1963 and, with her mother Larisa, moved to Philadelphia when she was 11.

Mama Larisa despised the Soviet government and its leadership and immediately gloried in America’s well-stocked Pathmarks and even delighted in her first job here as a housecleaner. But Von Bremzen, who had attended a fancy school in Moscow for the children of diplomats and Soviet honchos, missed her privileged status, symbolized by her access to Donald Duck stickers, Wrigley’s Juicy Fruit, and M&Ms.

In America, she cultivated a longing for her Soviet childhood: “Now, in Mom’s tiny kitchen in Queens, she doesn’t share my nostalgic glow.”

Taking one decade of the 20th century at a time, from the pre-USSR Russian Empire into Putin’s oligarchy, Von Bremzen swivels our attention from food to history and back again. There is no book quite like Mastering the Art of Soviet Cooking. Vivian Gornick’s famous memoir "Fierce Attachments" rings a bell. But Gornick’s heroines – her mother and herself – are presented as equally matched fighters. The wistful Anya and bitter Larisa, though often at odds, are less dramatic and work as a team. Larisa contributes research and skepticism, recollections and secrets, while Anya mediates and tries to make sense of her Proustian “poisoned madeline” of childhood food memories. (Which also reminds me of Lara Vapnyar’s comical "Broccoli and Other Tales of Food and Love Stories," where Russian food in America evokes memories, causes fights, often consoles and once even accidentally kills.)

Von Bremzen writes with a light air, paraphrasing after her own fashion – as all literary Russians do – the opening sentence of "Anna Karenina": “All happy food memories are alike; all unhappy food memories are unhappy after their own fashion.”

But Von Bremzen is never breezy about the USSR’s atrocities, most prominent of which was Stalin’s reckless and vengeful inducing of a catastrophe that starved an entire region: “In 1933 the country’s breadbasket, the fertile Ukraine, would plunge into man-made famine – one of the great tragedies of the twentieth century.... A dead peasant mother’s dribble of milk on her emaciated infant’s lips had a name: ‘the buds of the socialist spring.’ Out of the estimated seven million who died in the Soviet famine, some three million perished in the Ukraine.”

Von Bremzen scoffs at every Soviet leader from Lenin to Putin and describes each one’s affect on food production and cuisine. At reunion meals today, Von Bremzen and her mother and their guests recall the food lines, deprivations, and worse, during the Nazi siege of Leningrad, when more than a million Russians perished from hunger and cold. If your Soviet history is shaky, Von Bremzen and her mother will shore it up and reawaken you to its calamities. Von Bremzen also recounts – darkly comically – the desperate trip her grandmother made to besieged Leningrad to find and claim her husband’s body. (He wasn’t dead.)

The family’s personal history and character bring the Soviet era up close. There is no better contrast of the two women and their generations than this grim observation: “My mother has impeccable manners, is ladylike in every respect. But to this day she eats like a starved wolf, a war survivor gobbling down her plate of food before other people at table have even touched their forks. Sometimes at posh restaurants I’m embarrassed by how she eats – then ashamed at myself for my shame. ‘Mom, really, they say chewing properly is good for you,’ I admonish her weakly. She usually glares. ‘What do you know?’ she retorts.”

Yet, despite her mother’s renunciation of almost all things Soviet, Von Bremzen can’t help remembering her relatively contented childhood, where as a privileged grandchild of an important international spy, Naum Frumkin, she and her mother – despite their Jewish heritage in an anti-Semitic country – had special access to housing and consumer goods: “We were happy together, Mom and I, inside our private idyll, so un-Soviet and intimate.”

Von Bremzen’s philandering father, meanwhile, is a tragic figure, renounced by his emigrating daughter and wife, and then forgiven a dozen years later on the women’s return to Gorbachev’s crumbling Soviet empire. Invited to dinner by her father, Von Bremzen witnesses his previously hidden culinary talent: “With each bite I was more and more in awe of my father. I forgave him every last drop there was still left to forgive. Once again, I was the Pavlovian pup of my childhood days – when I salivated at the mere thought of the jiggly buttermilk jellies and cheese sticks he brought on his sporadic family visits. This man, this crumple-mouthed grifter in saggy track pants, he was a god in the kitchen.”

Through all of this lovely and moving memoir’s good humor, bittersweet reminiscences, and gorgeous evocations of food, there hangs the “toska,” the Russian nostalgic “ache,” of Anya and Larisa’s conflicted feelings about the past.

Bob Blaisdell, a frequent reviewer for the Monitor, edited "Essays on Immigration" for Dover Publications.