Hollow City

Loading...

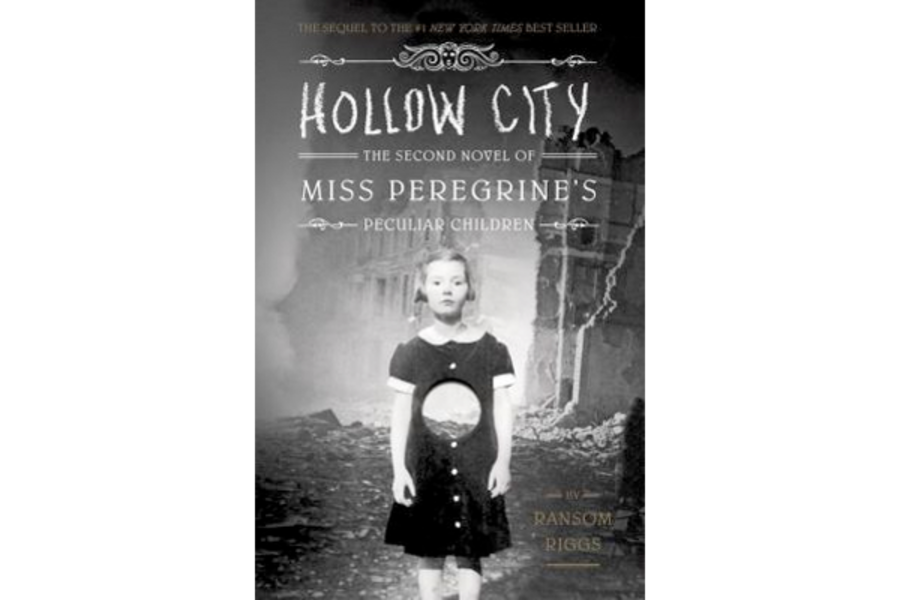

Hollow City, the second book of Ransom Riggs's "Miss Peregrine" trilogy, carries on in the great tradition of second installments. It’s packed with character development and emotional backstory – as well as the eerie vintage photographs that made the first book such a success.

In book one, "Miss Peregrine’s Home for Peculiar Children," Jacob Portman travels to a mysterious island off the coast of Wales to decipher his grandfather’s cryptic last words. He finds himself in a secret time vortex, known as a loop, with ten “peculiar” kids and their guardian, Miss Peregrine. Hidden from their paranormal nemeses, they endlessly relive one day in 1940.

Here, peculiar doesn’t mean kooky. Emma creates fireballs with her bare hands. Hugh commands an army of bees from within his stomach. Olive must wear weighted shoes or she will float away. Millard is invisible. Miss Peregrine is their ymbryne, a time loop guardian who can transform into a bird (ten points if you guess which one).

Jacob, as it turns out, is also peculiar. He possesses the rare ability that his grandfather also had: he can see their enemies, a race of invisible, tentacle-tongued monstrosities called hollows. Hollows prey on the souls of peculiars; if they consume enough, they turn into evil pupil-less men called wights. Lately wights have been invading loops, kidnapping ymbrynes, and killing peculiars. Jacob unwittingly leads one right to his friends.

In "Hollow City," Riggs picks up right where the first "Miss Peregrine" book left off. Miss Peregrine, kidnapped but then recovered, is on the cusp of being trapped in bird form, and the one person who can save her is the only other ymbryne who hasn't been captured: Miss Wren, of the London-based peculiar world headquarters. Miss Wren is therefore the best-hidden person in England and our heroes must find her.

In the final pages of the first book the children and their avian headmistress launch rowboats into the sea between their island and the Welsh mainland, their home a smoldering wreck behind them after a Nazi bombing run. One of the children takes a picture as they depart:

“Bronwyn lowered the camera and raised her arm, pointing at something beyond us. In the distance, black against the rising sun, a silent procession of battleships punctuated the horizon. We rowed faster.”

Close book one, open book two:

“We rowed out through the harbor, past bobbing boats weeping rust from their seams, past juries of silent seabirds roosting atop the barnacled remains of sunken docks….” It's a seamless transition that keeps the pace going.

The children forge a path to London, all the while loop-hopping, talking-animal-befriending, and hollow-battling to save their headmistress. They rally around each other in a ragged band, leaning on each other’s talents to survive. When they do reach London, it’s in the middle of the 1940 blitz. They must find Miss Wren, pray that she can heal Miss Peregrine, and figure out how to save their world.

Jacob, having only just discovered his gift, spends most of his time working to strengthen and expand it. He and Emma grow closer, a relationship that still makes me squirm since she was also the love of his grandfather’s life.

Second installments of trilogies are almost always about character development and relationships. Take the second movie of the original Star Wars trilogy, "Episode V: The Empire Strikes Back." You don’t watch that movie for epic space dogfights or lightsaber duels, though there’s certainly action. You watch that movie because you must learn about Luke Skywalker’s heritage and his struggle to grasp his own destiny. You watch it because only then can you understand the emotional impact of "Episode VI: Revenge of the Jedi."

In "Hollow City," we learn more about the peculiar world's lore and landscape and much more about the Peregrine kids. I loved discovering superhumanly strong Bronwyn's deep maternal side, even as I enjoyed thinking about Millard and what it would feel like to be invisible.

I was concerned initially that these books might be too scary. There’s a reason I don’t read Stephen King or watch "The Ring" – I’d have to turn on all the lights in the house! The creepy snapshots seemingly had the potential to tip the books into nightmare-inducing. But the more I read, the less scared I was, and soon I eagerly awaited each photo as a complement to the narrative. The deeper Jacob went, the more separate Riggs’s world seemed from the real world. Plus, it’s refreshing to have an eminently hate-able enemy – a definitely, decidedly, no-doubts-about-it villain.

If there’s one tiny flaw, it’s the sense of time. "Hollow City" takes places over three days, yet it feels more like two weeks. It was slightly disorienting, though I shouldn’t complain: our heroes are jumping in and out of time loops, after all.

"Hollow City" is a well of backstory sprinkled with enough near-miss danger to get your heart pounding. The cliffhanger sets up what will surely be an Act Three alley-oop. In the end, just like his grandfather, Jacob must choose between the soporific safety of the modern world and the exotic, thrilling nightmare of the peculiar world. Read the first, read the second, then gnaw on your fingernails until the last book drops.

Katie Ward Beim-Esche is the Monitor young adult fiction critic.