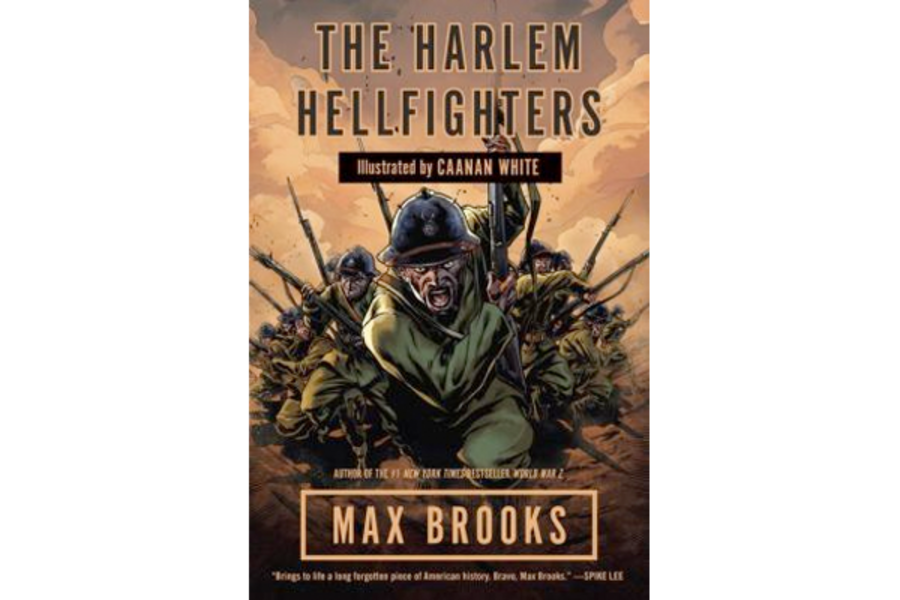

The Harlem Hellfighters

Loading...

Historians usually trace the outbreak of World War I to the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand, heir to the Austro-Hungarian Empire. A series of reactions quickly entangled the major European powers, and simmering rivalries over colonial ambitions made diplomatic solutions impossible.

But consider a different explanation. “White folks ran out of coloreds to kill, so they turned on each other.” This is the perspective of a character in The Harlem Hellfighters, a graphic novel by author Max Brooks and illustrator Caanan White that tells the story of the 369th Regiment, the first African-American infantry unit to fight in World War I.

As the regiment crosses the Atlantic to join the fray, a soldier asks how the war started. Another delivers an impromptu history lesson. “White folks own the whole damn world! Whaddaya think they've been doing the last 400 years?” First, he says, white folks spent their time “whippin’” the red folks; next they turned to the yellow folks, the brown folks, and the black folks. "When there isn't nobody colored left to whip, but whippin’ is all they know…. What else could they do but whip each other?"

The other soldiers are skeptical; “Ignorant,” one mutters. But whatever its simplifications, this account has the virtue of subverting official narratives of the origins of World War I. The struggles and achievements of the 369th Regiment have been erased from many histories of the war, so it makes a certain sense that Brooks depicts its soldiers as suspicious of standard explanations.

Consider President Woodrow Wilson’s famous declaration that America would join the war to make the world safe for democracy. His idealistic rhetoric collided with the disquieting truth that racial hatred excluded many Americans from participation in their own democracy. Brooks's narrator captures this irony perfectly. “In 1917 we left our home to make the world ‘safe for democracy.’ Even though democracy wasn't exactly ‘safe’ back home.” White sketches close-ups of a malign, snarling face to accompany these words, offering an arresting visual of hatred.

"The Harlem Hellfighters" likely required more historical research than "World War Z," Brooks's earlier novel of zombie apocalypse. Almost all the events in "The Harlem Hellfighters" are based on historical reality, and a thorough bibliography documents the range of his source material.

The novel's plot makes clear that for the men of the 369th, the European war was often a secondary conflict: the central struggle was between black and white Americans. Long before they were deployed, the soldiers of the 369th had to scrounge just to get basic supplies. They trained with broomsticks rather than rifles. The War Department preferred to donate actual weapons to private rifle clubs rather than to equip African American troops. The men resort to inventing nonexistent rifle clubs in order to obtain the necessary arms.

This is hardly the only obstacle they face. They are initially stationed in Spartanburg, S. C., where the mayor and the locals do their utmost to provoke fights that would ruin the soldiers’ chances of deployment to Europe. They are denied the chance to march in military parades, sent to Europe in an old ship that continually breaks down, and given menial service jobs unloading supplies once they finally arrive.

The American high command only allows the 369th to see action at the front when French troops are desperate for reinforcements and no other men are available. The French soldiers give the men a friendly welcome, but this seems more a function of desperation than racial tolerance. The French have their own checkered colonial legacy in Africa.

Brooks doesn't simply romanticize the men of the 369th; he's aware of the ugly motives that may have prompted them to fight. The same soldier who delivers the subversive history lesson explains his enlistment like this: “White folks payin’ me to kill other white folks?!?! Glory, hallelujah!” To present the soldiers only as noble patriots persecuted by an evil system would have made them caricatures. Instead, Brooks makes them human, and as such they are subject to the same distorting rages as members of any other race. The soldier doesn't seek revenge against particular white folks; he wants to kill them indiscriminately. No race, Brooks suggests, is immune to racism.

This moral complexity is just one of the novel's many achievements. Dialogue and imagery are often richly juxtaposed; in one frame, the word “hero” hovers beside the image of a soldier vomiting over the side of the ship. Heroism isn't all crisply snapping salutes and courageous charges at the enemy; it has a messy, unglamorous side as well. The trenches smell like a mixture of "charcoal, gunpowder, unwashed bodies, and rotten meat ... a lot of rotten meat." Even the good smells are treacherous; the scent of flowers, onions, and a hint of mustard signals the enemy releasing deadly gases.

White's illustrations render the grisly and graphic details of trench warfare with haunting immediacy. Rats swarm, bodies decompose, and soldiers sit slumped in poses of baffled shock. The sharp lines and shadowy depths of his sketches are absorbing and Brooks’ words are equally evocative. The dialogue is bleak, funny, and efficient. He uses just enough slang and dialect to capture the polyglot camaraderie of life in the trenches, and his careful historical research doesn't sap the story of its speed and strength.

Although harsh conditions and a common enemy did promote some sense of shared purpose among men of different races and nationalities, the soldiers of the 369th were never allowed to forget that they were considered inferior. One soldier sees an American plane fly overhead and imagines becoming a pilot himself. There would be no mud, no rats.... But another soldier interrupts his reverie with harsh but honest humor. “No way you ever gonna get to fly, ‘cept on the way to heaven. And that's if heaven has a colored section.”

Nick Romeo is a Monitor contributor.