'The Romanov Sisters' examines the lives of the royal siblings before their early deaths

An experienced biographer of British and Russian royals, Helen Rappaport presents us with the short, happy lives of the daughters of Russian Czar Nicholas II – four sheltered, earnest girls who never harmed a fly. Their little brother, Alexey, next in line to be czar, was the only other child the girls ever really knew: “The extraordinary closeness and self-sufficiency that was the mark of the four Romanov sisters persisted, as too their touchingly childlike innocence about the world.

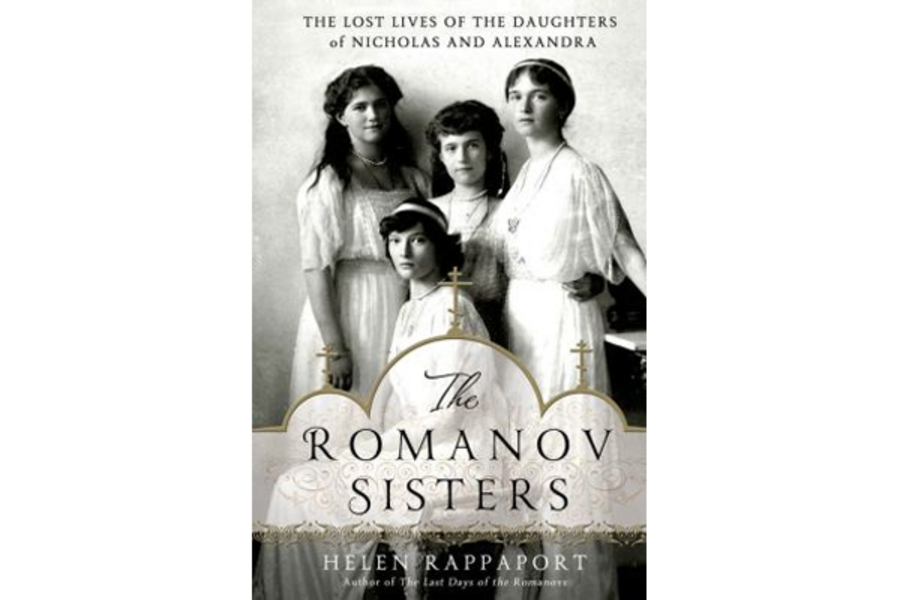

But it was a strange hothouse atmosphere in which to grow up,” writes Rappaport in The Romanov Sisters: The Lost Lives of the Daughters of Nicholas and Alexandra.

Because assassinations of Russian government officials were not uncommon during Nicholas’s reign, which began in 1894, security was tight, and the czar and his family retreated from the public: “As a result, the Russian people, as one London paper observed, had absolutely no sense of the ‘sweet family life’ of their tsar and tsaritsa.’ ”

In their time, Olga, Tatiana, Maria, and Anastasia were depicted in international accounts as a cute, indistinguishable quartet. But Rappaport brings out each one’s character and does it neatly, with a fine touch. The only occasionally unsympathetic member of the czar’s family is Czarina Alexandra, who, though a loving and engaged mother, seems to have been a hypochondriac who spent long periods in bed.

Nicholas was stubborn about maintaining his power but apparently not skillful at using it. Rappaport’s focus, however, is on the arena in which he excelled: “History may have condemned him many times over for being a weak and reactionary tsar, but he was, without doubt, the most exemplary of royal fathers.” (Rappaport is mum, for the most part, about the frustration and anger that Nicholas’s repressive measures created, preferring that we blame wily charlatan Rasputin.)

While we know that the family’s fate will be tragic, the girls don’t, and Rappaport, with a light hand and admiring eyes, allows the four Grand Duchesses to grow on us as they grow up. When World War I erupted in 1914, the two eldest girls, Olga and Tatiana (then 19 and 17, respectively), took up nursing: “The Romanov sisters and their mother were not spared any of the shock of their first confrontation with the suffering of the wounded.... [T]hey were thrown in at the deep end, dealing with men who arrived ‘dirty, bloodstained and suffering’ ” and yet they took it well.

Variably rambunctious, moody, cute, and hardy, the girls invited the sympathy of those who met them, particularly after the family was taken captive and stripped of their privileges in 1917. “‘The family is bearing everything with great sangfroid and courage,’ ” reported an aide of Nicholas’s in Tobolsk, where they spent several months: “ ‘They apparently adapt to circumstances easily, or at least pretend to, and do not complain after all their previous luxury.’ ”

An engineer in Ekaterinburg, the family’s final stop in captivity, had hated the sisters for their position, yet relented when he saw them in person: “ ‘It felt that my eyes met those of the three unfortunate young women [Maria was captive elsewhere in town, accompanying her parents] just for a moment and that when they did I reached into the depths of their martyred souls, as it were, and I was overwhelmed by pity for them – me, a confirmed revolutionary.’ ”

When White Army forces began making a move toward Ekaterinberg, the Red revolutionaries there had the ex-czar and his family murdered on July 17, 1918, in the name of order and in the spirit of vengeance.

Bob Blaisdell reviews books on Russian history and literature.