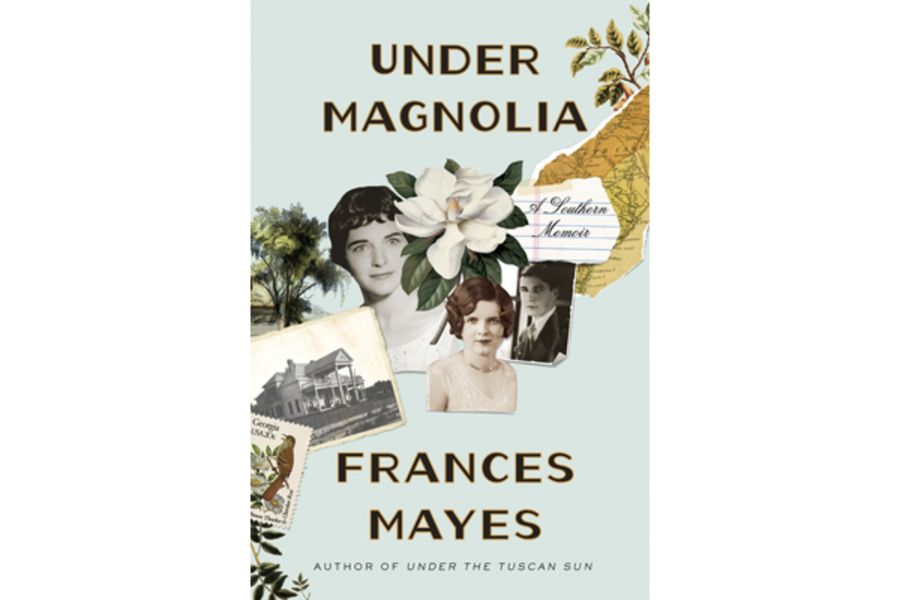

'Under Magnolia' follows Frances Mayes back to her roots in small-town Georgia

Loading...

With the publication of "Under the Tuscan Sun" in 1996, Frances Mayes established herself not only as a bestselling writer but as a corporate commodity. Mayes's popular memoir of the charming life she built while restoring a villa in provincial Italy spawned a cottage industry of related projects, including a movie, several literary sequels, and even a Frances Mayes furniture line.

That kind of branding can reduce an author to a franchise, a creature of formula rather than revelation. But in "A Year in the World," Mayes's 2006 travelogue, she displayed a willingness to leave the almost uniformly pastel tone of her earlier books to touch on darker complexities. She recounted a disturbing visit from a delusional visitor to her San Francisco home; the Sept. 11, 2001, terrorist attacks; and what these deeply disruptive tragedies taught her about the continuing need to seek wonder in the everyday.

Under Magnolia, Mayes's new memoir of her Southern youth, marks an even greater departure from her Tuscan books, although fans of her European sojourns will find much to like in her account of life in post‑World War II small-town Georgia. She begins "Under Magnolia" by explaining how her Southern heritage informs her love of Mediterranean culture:

"The complex interconnections of family and friends, the real caring for one another, the incessant talk, emphasis on ancestors, the raucous humor, the appreciation of the bizarre, the storytelling, the fatalism, the visiting, the grand occasions – in both Tuscany and the South these traits offer an elaborate continuity for solitary individuals. Deeply fatalistic, Southerners, again like Tuscans, can be the most private people on the globe."

Beyond this analogy, Tuscany remains largely offstage in "Under Magnolia." The abiding landscape of the book is the terrain of the former Confederacy – a place, writes Mayes, where nothing "stirs me as much as the narcotizing fragrance of the land, jasmine, ginger lilies, gardenia, and honeysuckle blending, fetid and sweet."

That passage, in which the scent of transcendence blithely mingles with a hint of death, underscores the complicated sensibility of Mayes's story.

Nostalgia alternates in her memoir with the sharp stab of mortality, suggesting that Mayes not only recognizes the fatalism of her fellow Southerners but often embraces it. Admiring the region's iconic flower, the magnolia, she asks, as if offering the perfect compliment, "What other flower is there to lie on the dark wood coffin of your father?"

"Under Magnolia" is full of constant reminders that its author has devoted part of her career to writing and studying poetry. Even when she crafts prose, Mayes's paragraphs prove as musical as verse. As with her other books, I began "Under Magnolia" by jotting down memorable passages – only to realize, after the first chapter, that I'd been reduced to a court stenographer, essentially copying the entire text.

Silver sentences gleam from every page. "Noon burns the whole town to stillness," she notes in recalling Southern summers. She writes of church candles that "slowly give up to the heat and droop over like the necks of swans bending toward fish under water." Gazing into the eyes of a father ravaged by a fatal illness, Mayes recalls that "it's like looking into old campfires."

Mayes writes of her past in both the past and present tense, which is sometimes confusing. There are also a few false notes in her account of a college romance, the imagery indulging the excess of a Harlequin paperback: "He lies on top of me and through our summer clothes I feel the entire velocity of his body on mine, feel our bright holy skin, a swarming fierce right."

But those are quibbles in a book that promises to satisfy Mayes's fans and attract some new ones. Her memoir of a Southern childhood would be right at home in a Tennessee Williams play, and like Williams, she avoids easy resolution. She's discovered that "what one finds in the enterprise of writing is that there is no bottom. Only a contraction into the rhythmic, blood-pumping heart of the past and sometimes an expansion out of it."