'Tomlinson Hill' tells the parallel stories of two Tomlinson families: one white and one black

Loading...

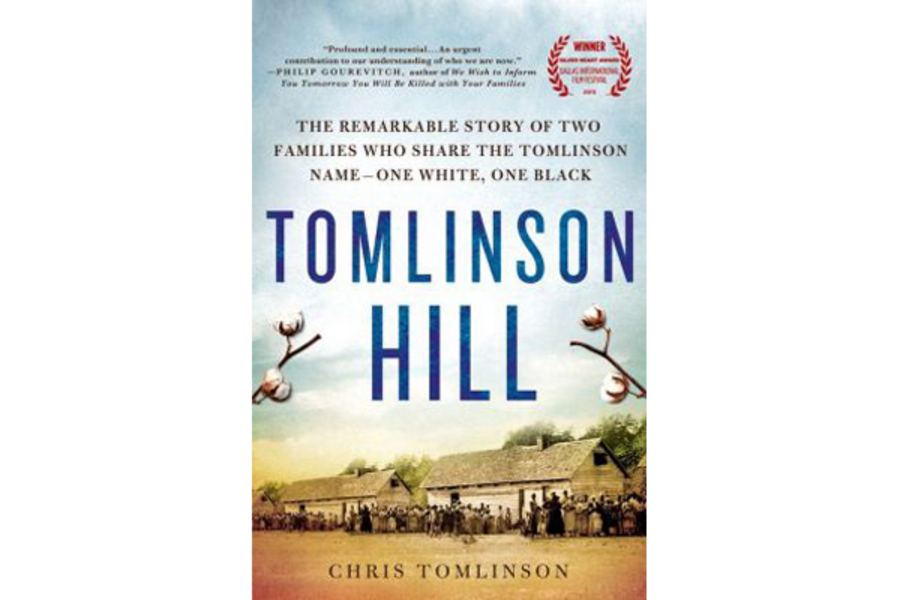

Researching and mapping out one’s family history is often cited as one of the top hobbies in America, but in his new book, Tomlinson Hill, former Associated Press correspondent Chris Tomlinson takes curiosity about personal history to another level altogether. He also proves remarkably bold and determined to face his direct connections to one of the ugliest blots on American history: slavery.

Since childhood, Tomlinson was fascinated by Tomlinson Hill, his family’s namesake land plot, and its ties to a family history that was as celebrated as it was mysterious. So in a more advanced version of his childhood perusal of family scrapbooks, Tomlinson searched through countless Falls County records to learn about the lives of his ancestors. Along the way, he discovered the story of the other Tomlinson family – the African-American family, descendants of his ancestors’ slaves (who also happened to be the family of famous San Diego Chargers running back LaDainian Tomlinson).

Tomlinson had always been told that his fifth-generation Texan pedigree was something to celebrate, and he was raised with a rose-colored view of the South and its “noble” antebellum history. His great-great-grandfather Jim’s sister Susan Tomlinson Jones was the first Tomlinson to live on the Hill in 1854, joining her husband, Churchill Jones, who had already established a cotton plantation flourishing on the exploitation of slaves. Jones would soon become one of the wealthiest and most politically active members of his community.

The family took root, becoming true members of the growing city of Marlin. They experienced the ups and downs of each life cycle, and race became the rigid yet unquestioned determinant of each family member's way of life. The coming years would take the Tomlinson family on and off the HiIl. The last white owner chronicled in the book sold off many parcels of the original plantation to various members of the Tomlinson family and their relatives and friends, hence the creation of the close-knit Tomlinson Hill community.

The parallels and disparities that unite and divide the white and black families are stark. While three generations of white Tomlinsons attended Texas A&M University, former sharecropper Charles Tomlinson recalls a very different perspective on education, saying, “I could read and write.That’s what my dad said you are going to learn in school anyway, read and write and knowing to subtract so he white man will not cheat you out of everything you got.” Later on, while the author attended a brand new public school equipped with a private pilot's training ground and many helicopters, LaDainian’s mother Loreane was scrimping to send him to the Boy’s and Girl’s Club in Waco.

Putting together the family’s history as the Civil War, Reconstruction, and the civil rights movement tear through Texas, Tomlinson is quick to point out that each generation of the white Tomlinson family made the conscious decision to continue participating in a racist system that ensured power by keeping others down. This is a brave move on Tomlinson's part, not only because he is willingly accepting culpability as part of a family narrative long considered noble, but because he takes the reader through the exact decisions taken by his ancestors to allow them – and him – to enjoy generations of white privilege.

However, Tomlinson’s historical explorations, while extensive and for a noble goal, are often over the top. Although the evocative details of what each generation of each family ate and how factors like climate and social unrest affected them individually are interesting and help to portray them as real people, the same cannot be said of reports on the family’s specific debts and the winding lives of distant relatives, inclusions which start as annoying and soon drag the story down. The lack of a thorough visual family tree or chart is also confusing given the Tomlinson family’s repetition of names over the years, as well as the narrative's cutting back and forth between the author's family and that of LaDainian.

But for readers fascinated by family legacy, "Tomlinson Hill" offers a very thoroughly fleshed-out account of the generations descending from one extended household divided into two by race. The story also offers an interesting perspective, on a smaller scale, on the culture and history of Texas itself.

Tomlinson's narrative sometimes becomes convoluted. But in an America still troubled by racial divisions, this story of two different families moving in very different directions because of the color of their skin is both relevant and valuable. Not only does it allow one man to make peace with his past, but it also helps to shed light – for all the rest of us – on the sometimes painful reality of how we got to where we are today.

Caroline Kelly is a Monitor contributor.