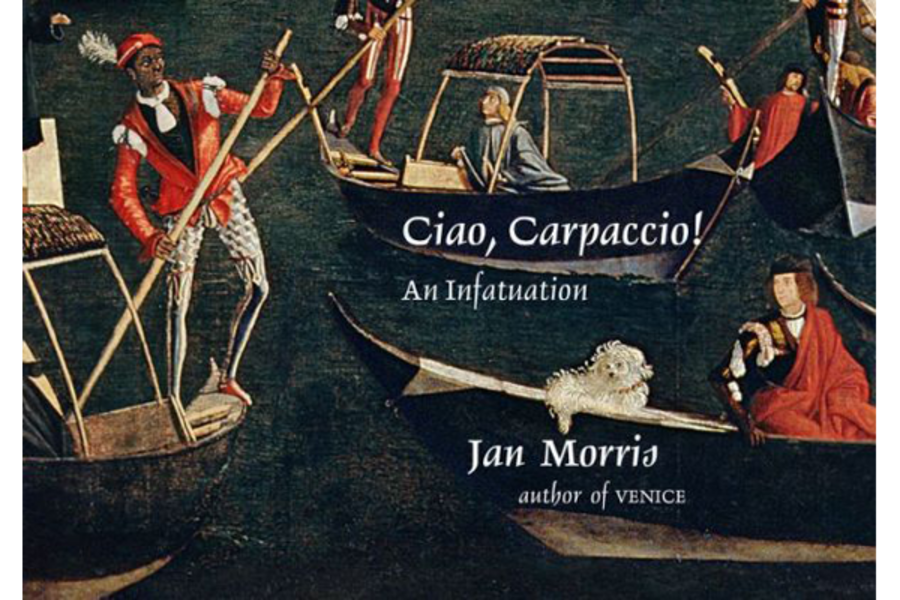

'Ciao, Carpaccio!' is travel writer Jan Morris's loving meditation on Venetian painter Vittore Carpaccio

In a literary career spanning more than a half a century, Welsh author Jan Morris has become one of the world’s most celebrated travel writers, with acclaimed books on Venice, Spain, and Hong Kong to her credit. But at 88, limited in her globetrotting by advanced age, Morris does most of her traveling these days vicariously, by armchair.

It’s in this spirit that she undertook her latest book – and what’s been billed as her final one – a reflection on the 15th-century Venetian painter Vittore Carpaccio. Sitting by the fire one evening, and revisiting a book of Carpaccio’s paintings, Morris spotted a tiny bird in a tree within the background of a picture of an armored nobleman, “Portrait of a Young Knight.” The creature was so tiny that Morris had to magnify the image to identify it. “Instantly, susceptible as I was by the woodfire with my wine, I recognized that bird as the spirit of Carpaccio himself, and I heard it calling to me joyously out of the centuries like an old acquaintance,” Morris tells readers. “I was elated. In my mind I returned the greeting – Ciao, Carpaccio! Come sta? – and before I went to bed I resolved to write, purely for my own pleasure, this self-indulgent caprice.”

In describing her connection with Carpaccio so mystically, Morris points to the ethereal nature of his art, which is abidingly surreal. That sensibility deeply informs his “The Dream of St. Ursula,” which depicts an angel warning the painting’s title character about her coming martyrdom. Carpaccio’s treatment of the scene is strikingly understated. An angel stands quietly by Ursula’s bedside, and the scale of the bedroom makes the heavenly visitor and Ursula seem surprisingly small. The viewers’ eyes instead wander toward the picture’s domestic details.

“The bedtime book she has been reading is open on her table, and there are potted plants on the window-sills,” Morris notes. Carpaccio’s painting suggests that communion with the cosmic isn’t necessarily extraordinary, but can dwell within the fabric of everyday life. That message comes across subtly, as do most of the observations in his paintings. Carpaccio made much of his living through commissions for religious art, a reality that obligated him to respect the pious tastes of his sponsors. Yet within these constraints, Carpaccio often managed to strike a mildly subversive note.

In a painting of St. Jerome bringing a newly tamed lion back to his monastery, his fellow monks flee in terror from the animal, unaware that it’s been rendered harmless. The lion’s comic expression seems a sly commentary on human folly. Equally mordant is Carpaccio’s study of St. George slaying a dragon that had terrorized the mythical Libyan city of Silena. As Carpaccio depicts the forlorn monster on the verge of death, we feel more sympathy for the dragon than the saint.

It’s this slyness that Morris admires so much in Carpaccio. “I like to think he addresses me almost as an accomplice,” she confesses. Her intimacy with the artist unfolds in spite of – or perhaps because of – the vagueness of his origins.

Little is known about Carpaccio’s life, an absence that appears to sharpen his appeal for Morris all the more.

That dearth of biographical detail means that Morris’s book about Carpaccio is necessarily speculative, but then again, she’s accustomed to this kind of technical challenge. In “Fisher’s Face,” her 1995 book about Lord Admiral Jack Fisher, Morris elaborated the story from a single photograph of Fisher, its presence a kind of talisman guiding her narrative. Morris’ prevailing idea – intense observation as a means of intellectual and spiritual revelation – rests at the center of her travel writing and her love of art, and it resonates in her discussion of Carpaccio, too.

In a humorous aside, she mentions that most people know Carpaccio these days as a menu item – Beef Carpaccio, a dish of raw meat slices named in honor of the artist because its red color reminded a chef of Carpaccio’s characteristically red pigments. But the reference also hints at her relation to Carpaccio’s art. Morris doesn’t merely want to see his paintings; she aims to consume them.

But Morris calls her extended essay on Carpaccio an “infatuation” and a “caprice” – language that seems intended to lower expectations for the book’s ambitions. “Ciao, Carpaccio!,” is, in fact, a small volume, often inconveniently so. Carpaccio created large works; his painting of the Winged Lion of St. Mark is 12 feet long. Even a typical coffee-table book would be hard pressed to suggest his original scale. But “Ciao, Carpaccio!” is hardly bigger than a chapbook, so its reproductions of his pictures are necessarily cramped. Reducing Carpaccio this much is like putting a prairie on a postage stamp.

The tiny format proves portable, though – easily slipped into a tourist’s pocket. Morris doesn’t mean her book as a substitute for Carpaccio’s paintings, but an invitation to see them up close. She even includes detailed directions to the School of St. George of the Slavs, a Venice institution that hosts many of Carpaccio’s pictures. She poses that trip as a journey into geography – and time.

“I feel I know him personally,” Morris writes of Carpaccio, “and I often sense that I am directly in touch with him across the centuries, across the continents, as one might be in touch with a living friend.”

– Danny Heitman, a columnist for The Advocate newspaper in Louisiana, is the author of “A Summer of Birds: John James Audubon at Oakley House.”