My New Year's resolution: read more John Updike

Loading...

On New Year’s Day, a time for plans to do big things, here’s a resolution for readers to consider:

In the coming year, why not resolve to read one author clean through – all of his books from beginning to end? It’s not the way that most of us like to read, I’ll grant you. With reading, as with everything else, variety is the spice of life, and there’s a lot to be said for randomness in reading – sampling a lot of voices, rather sporadically, as if hopping between guests at a cocktail party. That’s how I read in most years, and the pleasure it’s brought me has been undeniable.

But I’m wondering if there’s also some alternate reward in the sustained company of a single writer, book after book, until the eyes reach the last page of his oeuvre. There’s the chance, I suppose, to see an author grow on the page as you visit his early books, the middle ones, the later ones that top off a career. And there’s the promise of intimacy, too – the kind of closeness that develops, like any friendship, according to the number of hours one is willing to invest in it.

All of this comes to mind because this year, I’ve decided to read as much John Updike as I can. He appeals to me because, quite frankly, I finally have a decent chance of finishing one Updike book before another one comes out. Updike died six years ago this month – in January, 2009 – but he was too prolific a writer to let something as small as death completely stop his output. Posthumous collections of his work have appeared since his passing, but there must be an end to that stockpile at some point. What we now have, finally, is the prospect of seeing Updike whole. That’s a territory I’d like to explore the next 12 months, continuing a journey started many years ago.

I first connected with Updike as a college student, in “The Norton Anthology of American Literature” – that heavy brick of a book, with hundreds of tissue-thin pages, that has the comprehensive breadth of a phone book, the ambition to include every major scribe in our national letters. The Norton arranges its material chronologically, so Updike sat at the back of the book – too far behind, in fact, for my professor to get to him before the semester ended.

If we wanted to sample Mr. Updike, we were told, we were on our own. On a whim, I dipped into an excerpt of “Self-Consciousness,” Updike’s memoir, that was included in Norton’s selections. Updike’s acute perception – his ability to record the inner life of his childhood with such luminous detail – was a small miracle to me. He seemed like a writer I should get to know.

Several years later, fresh from college and new to my newspaper career, I ordered a copy of Updike’s “Assorted Prose” one winter, and the pleasant companionship of that book accompanied me through the spring. As a student, I’d learned the old truism that you should write what you know, a platitude that comforted me with its promise of writing as something easily intuitive, a craft that drew on what was already in your brain.

Reading Updike’s collected essays and criticism, though, revealed a corollary to the write-what-you-know principle. If writing drew on what you knew, as Updike’s career suggested, then it was also true that the more you knew, the more good stuff you could write.

And Updike, God bless him, seemed intent on learning everything. In “Odd Jobs,” one of his later collections of criticism, Updike said that he was most thrilled by the freelance assignments that gave him the most trouble. In the struggle with new material, he added new lessons to his store of knowledge.

Updike is known primarily as the novelist behind the “Rabbit” series, a string of novels exploring the predicaments of life in affluent suburbia. But he was also a supremely gifted literary critic, occasional essayist and writer about art, an interest that grew from his early desire to be a painter.

The topics in “Assorted Prose” are a bright magpie’s nest of subjects, ranging from baseball to the post office, Robert Frost to unread books, dinosaur eggs to the assassination of John F. Kennedy. He seemed incapable of writing a bad sentence, which is another reason I wanted to read more of him this year. There’s always the hope, in immersing oneself in such a consistently calibrated prose stylist, that his eloquence will, in some small way, perhaps become your own.

Until recently, reading Updike’s backlist meant scouting out-of-print titles in the used book market. But Random House has reissued most of Updike’s older material in durable, elegantly designed softcovers.

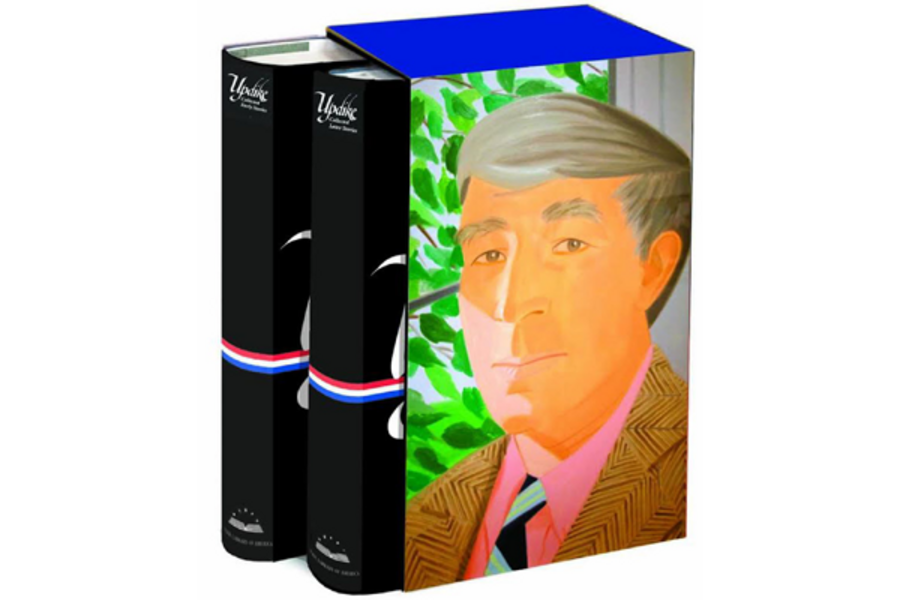

They’re here before me as I write this –“Odd Jobs,” “Hugging the Shore,” “Picked-Up Pieces,” “Self-Consciousness.” Meanwhile, The Library of America has collected Updike’s short stories in a beautiful, two-volume set, also on my 2015 reading list.

Those books, along with the Updike novels, should keep me busy this year. I’ll read other things, of course, but I hope to make this my Updike Year.

Consider an Updike Year for yourself in 2015, or a Faulkner Year, a Twain Year, even a Stephen King Year.

In our attention-starved culture, I hope that following one writer, over time, will make me a better reader – and a better person – by the time that another New Year’s comes around.

Danny Heitman, a columnist for The Advocate newspaper in Louisiana, is the author of “A Summer of Birds: John James Audubon at Oakley House.”