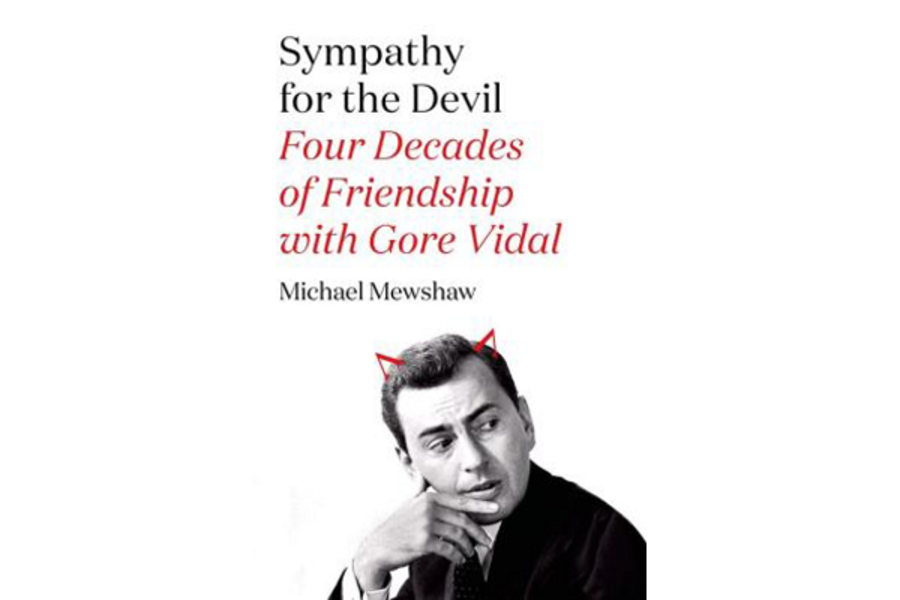

'Sympathy for the Devil' presents an often unlovely portrait of Gore Vidal

Loading...

No one would call Gore Vidal a big old sweetie pie, but some people who knew him were aware that this most acerbic of wits and nettlesome of contrarians could be generous and kind. One such is Michael Mewshaw, a freelance journalist and novelist, whose Sympathy for the Devil: Four Decades of Friendship with Gore Vidal purports to be what its title suggests: a memoir of friendship, and it is that, I guess, in the sense that Mewshaw occupied the position of friend. As such, he is able to show us aspects of Vidal – fastidious and unflappable in his public persona – that the man might have preferred to remain private; specifically a few instances of quiet benevolence and discreet charity, and many more of anger, resentment, churlishness, and drunkenness.

The book begins benignly enough with Mewshaw in Rome for a year with his wife and infant son. Acting on the recommendation of a friend, he phoned Vidal and found himself speaking to “the frosty patrician voice that had launched a thousand insults.” The great man invited Mewshaw and his wife over for drinks and regaled them with some excellently uncharitable observations from his well-polished stock, among them that Françoise Sagan is “a magnum of pure ether” and that the “three saddest words in the English language” are “Joyce Carol Oates.”

Mewshaw moved around, staying at various times in Rome, the United States, London, and Paris, and there he entertained and was entertained by Vidal, who also advised him on literary matters, granted him interviews, and permitted himself to be the subject of articles. When Mewshaw was having trouble finishing a book in a cramped apartment in Rome, Vidal lent him his aerie, Villa La Rondinaia, above Ravello on the cliffs of Amalfi, a place of solitude, rampaging drafts, and deep chill. Mewshaw seems to have been assiduous in introducing his friends and associates to Vidal, and often enough, his accounts of these affairs include reports of Vidal’s unfortunate, alcohol-fueled misdeeds and misfortunes. His description of Vidal in 2009, three years before his death, gives an idea of the spirit of this book: “He looked like a down-and-out panhandler who had sneaked in off Duval Street to swipe a drink and a fistful of peanuts. A sad, shrunken doll in a rumpled blue blazer with an antimacassar of dandruff around the shoulders, he wore stained sweatpants and bright red tennis sneakers and sat slumped to one side in his wheelchair, as if the bones had been siphoned out of his body.”

For all his asserted friendship with Vidal, Mewshaw laments the central quality that, in addition to his puncturing wit, set the famous gadfly refreshingly apart from most public pontificators: his willingness to speak the absolute truth, as he saw it, on political matters, no matter whom he offended. Mewshaw blames his friend’s especially unpopular statements on paranoia and booze, the latter being responsible, in his view, for Vidal’s “penchant for ignoring nuance and pronouncing opinions that a man of his acumen should have recognized would prompt a backlash.” (When, wonders the student of history, did Gore Vidal ever not court and welcome a “backlash”?) Mewshaw suggests that, in the case of Vidal’s stance on Israel, he should have apologized for having been misunderstood – a strange idea even in this age of endless apology, though especially as Vidal’s views on this contentious subject were routinely and deliberately mischaracterized.

Some explanations for the special flavor of this book occur to the dismayed reader. One is that it is simply a product of the natural human desire to speak ill of others, but another is more particular, an animus arising out of Mewshaw’s characteristically American hostility to artifice and lack of earnestness. (One of Vidal’s most memorable aperçus: “I like to think I have depths of insincerity yet unplumbed.”) It gets Mewshaw’s goat that Vidal presented himself as a patrician model of cool reserve and witty distance when, in fact, “for all his pretense of detachment, Gore seethed beneath the surface with infantile rage.” Just look at Vidal’s memoir, "Palimpest". “Where,” wonders Mewshaw, “was the anger, the rankling resentment at his exclusion, the humiliation, the professional and personal disappointments, the drinking, and the yearning for death?” In Mewshaw’s opinion, “the greatest flaw in 'Palimpsest' was Gore’s refusal to come to grips with his inner life, with painful traumas he suffered in private while he sustained the impression in public of perfect equanimity.” For my part, it strikes me as not very nice that Mewshaw would want his friend to abase himself in that therapeutic manner, but then I prefer wit, irony, and the sparkling apothegm – all abundant in "Palimpsest" — over soul baring, weeping, and the gnashing of teeth.

Though Mewshaw comes off as a tut-tutter and tale bearer, I will not say that his book has no redeeming qualities. It is not boring, relaying gossip aplenty about writers, expats, celebrities, and the penises of the stars, as well as hair tips from Howard (Vidal’s longtime companion) and thoughts on air pollution. Even Mewshaw’s long accounts of his own freelancing woes are interesting, at least in this quarter. Beyond that, unlike most of Vidal’s own writings, "Sympathy for the Devil" will bring joy to the righteous hearts of Gore Vidal’s many detractors.