'It's What I Do' tracks the life of a photographer working in the world's most dangerous spots

Loading...

Early in her memoir, photojournalist Lynsey Addario quotes the blunt advice of another photographer: “If your pictures aren’t good enough, you’re not close enough.” Addario works amid the anarchy of war zones and recently toppled governments, so getting close to her subjects is sometimes a risky proposition. She was in Libya after Qaddafi announced that any journalists his forces captured would be killed or detained. She was in Afghanistan when photography of any living being was illegal.

As an unmarried American woman, Addario is often particularly vulnerable. In one scene, she gets lessons from her female Pakistani interpreter on how to walk in a burqa without attracting attention. Even when veiled, women with an overly confident gait could arouse suspicion. On another occasion, she snaps pictures as an angry mob of Pakistani men burns effigies of President Bush and screams “Down with America!” Several male photographers shoot photographs without incident, but Addario must fight off a pack of men who grope and clutch at her body.

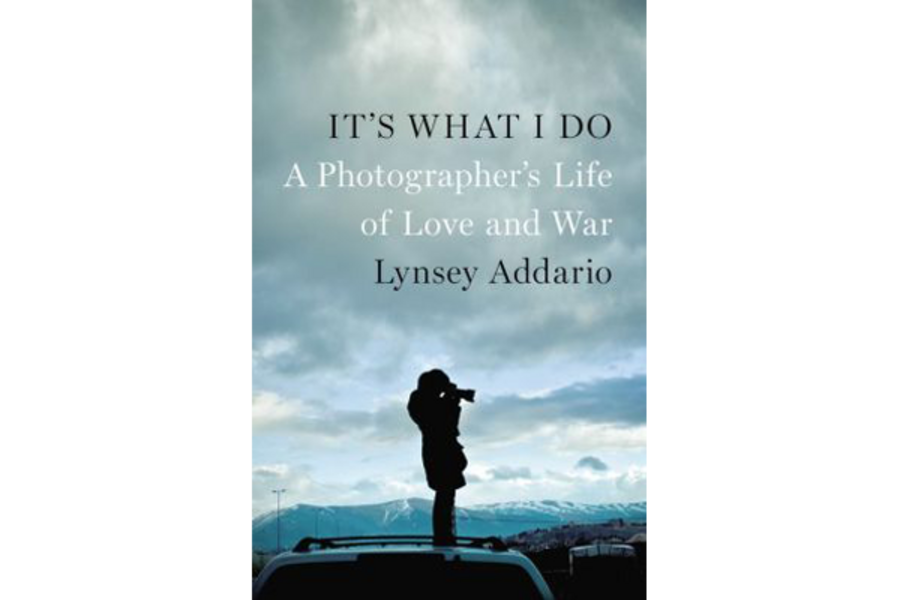

In It’s What I Do: A Photographer’s Life of Love and War, Addario narrates her global travels as a photographer and a string of failed romances that finally ends when she meets the man who becomes her husband. The two types of material can feel jarringly different. One moment she is eating buffalo wings and drinking wine with a hip group of expatriate journalists in Istanbul; a few days later she might be photographing rape victims in the Congo or documenting a bloody ambush of American troops in Afghanistan.

These disorienting contrasts are meant to evoke the confusing swirl of her life. She notes that many conflict photographers seek solace in drugs or alcohol, and the surreal distance between the different worlds she inhabits makes it easy to see why such self-medication might be necessary. The apparent normalcy of a stable society with a functional government can seem quite bizarre after spending enough time in certain parts of the world.

Addario has accumulated a long list of near-death experiences during her career. She was kidnapped twice, once in Iraq and once in Libya; she has worked in the notoriously dangerous Korengal Valley in Afghanistan; and she has survived car crashes, gunfights, angry mobs, and sundry other existential threats in volatile regions around the globe. She repeatedly wonders – as do her friends, family, and romantic partners – why she feels such a powerful need to continue pursuing such perilous work.

Her memoir suggests several explanations, some more laudable than others. The basic assumption behind much of her work is that photographs are a powerful way of raising awareness of otherwise neglected truths: the humanity of America’s ostensible enemies, the enormous toll that warfare takes on young Americans, the suffering of ostracized rape victims in Darfur. The book includes many of her photographs, and the arresting and evocative images are compelling reminders of important truths.

What seems more dubious is the tendency to aestheticize imagery of enormous suffering. At one point, Addario begins selling photographs of refugees in Darfur to art collectors for thousands of dollars. “I was conflicted about making money from images of people who were so desperate,” she writes, “but I thought of all the years I had struggled to make ends meet to be a photographer, and I knew that any money I made from these photos would be invested right back into my work.” This is not very convincing as a justification of her choice; it seems worth considering whether that money would have more of an impact if invested in a particularly effective NGO or charity.

At one point she does use her photography to raise funds to help women get fistula repair surgeries. In another scene Addario insists on taking a sick woman to the hospital, despite the protests of aid workers and UN staff traveling with her. Both episodes raise deeper questions about the ethics of detachment and intervention that haunt the book. There are many scenes where it’s hard not to wonder whether taking photographs is the most responsible course of action. When American soldiers scream at her not to photograph an explosion that wounded one of their own, she interprets the episode as an attempt at censorship. More plausible is that the grief-stricken soldiers wanted to preserve some semblance of privacy.

Another unsavory source of motivation is competition between journalists. Because multiple photographers representing various publications often work in a given area at the same time, whoever is most willing to risk life and limb often emerges with the best photos. This is an understandable dynamic, but it’s a far cry from some of her idealistic rhetoric about improving the world through photography. And Addario's frequent name-dropping of prizes and publications does suggest that her motives are more complex than simple altruism. She opens with the photographer’s adage that if your pictures aren’t good enough, you aren’t close enough. But it’s hard not to feel by the end of the book that if you are close enough, maybe simply taking pictures isn’t always good enough.