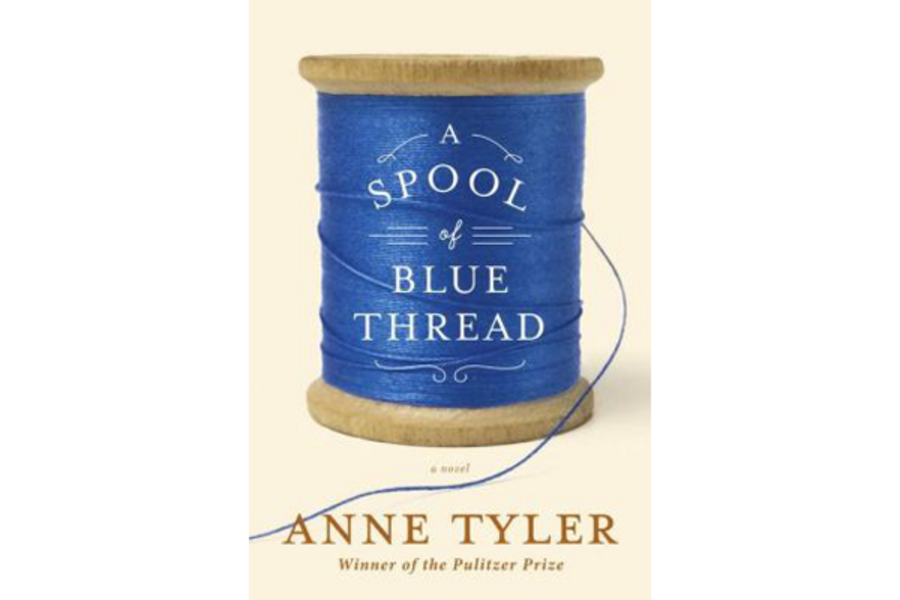

'A Spool of Blue Thread' gives fans one more reason to love Anne Tyler

Loading...

When Junior Whitshank built the house on Bouton Road, he wouldn’t allow any fussiness – no stained glass, no pretensions. The fact that he was building the house for a wealthy businessman and his wife and not himself in no way deterred the carpenter from vetoing any idea that compromised his vision of quality.

The end result was "a house you might see pictured on a thousand-piece jigsaw puzzle, plain-faced and comfortable, with the Stars and Stripes, perhaps, flying out front and a lemonade stand at the curb." That house, with its long front porch, more than any other in Anne Tyler’s work, is central to A Spool of Blue Thread, It’s not a Manderley or Tara, but it serves as the same kind of touchstone to its characters, in this case representing the tantalizing promise of a happy family life that proves so illusive in Tyler’s novels.

After he completed his masterwork, Junior couldn’t bear to let it go, scraping up the money necessary to buy the home from the businessman after the businessman’s wife decided she’d rather live elsewhere. (Said wife may have had a little help coming to that decision.)

That was one of the stories the Whitshanks always told one another. Another belonged to Junior’s daughter, Merrick, a social-climber without conscience who lands her best friend’s fiance – trust fund, alcoholism, and all.

And then there was the more hopeful one that Abby, a social-worker mom who was always dragging “lame ducks” home for dinner, who would tell her four children about the afternoon she fell in love with Red, Junior’s son: “It was the prettiest afternoon, all breezy and yellow-green with a sky the unreal blue of a Noxzema jar."

But none of the stories are quite as simple as they appear on the surface, as readers discover in “A Spool of Blue Thread,” Tyler’s 20th novel and easily her most satisfying since 2006’s “Digging to America.”

“A Spool of Blue Thread” deserves to stand among Tyler’s best writing, such as “Dinner at the Homesick Restaurant” and the Pulitzer-winning “Breathing Lessons.” It offers echoes of her earlier works – from the use of a sudden death as a catalyst, to squabbles over the family dinner table (and who gets to make it), to the Whitshanks’ self-made mythology, which glosses over disappointment and recalls her summation of the Bedloes of “Saint Maybe,” always and forever my favorite book by Tyler. Like the Bedloes, the Whitshanks have a “talent for pretending that everything was fine.”

“There was nothing remarkable about the Whitshanks. None of them was famous. None of them could claim exceptional intelligence. And in looks, they were no more than average,” she writes. “But like most families, they imagined they were special.... They made a little too much of the family quirks.”

Tyler, of course, has been making much of family quirks for 50 years now, since her first novel was published in 1964. The novelist, a master of the minor key, avoids fussiness in her own writing, preferring plain speech the way Junior preferred plain lines in construction. To complain that her novels always revolve around family life in Baltimore would be like complaining that Monet was overly fond of his garden.

“A Spool of Blue Thread” opens when Abby and Red Whitshank get a late-night phone call from their son Denny, the black sheep, who always felt neglected even though Abby adored him above all of her children.

Wondering what to do about Denny, a college dropout with serial careers and an uncertain marital status, consumes so much of Abby’s and Red’s consciousness that the other three kids – Jeannie, Amanda, and Stem – are free to fumble their own way to adulthood.

Aside from that brief period when an interloper had temporary possession, Whitshanks have always lived in the house at Bouton Road. So when Abby starts forgetting things and wandering off on walks and Red, increasingly deaf, has a minor heart attack, the idea of an assisted-living apartment is quickly discarded.

Instead, Stem and his preternaturally serene wife, Nora, move back in to Bouton Road with their three kids. It is the Christian thing to do, and therefore, Nora will do it – effortlessly infuriating Abby in the process with her command of the kitchen and her insistence on calling Abby “Mother Whitshank.” (“It made Abby sound like an old peasant woman in wooden clogs and a headscarf.”)

If four adults, three kids, and two dogs weren’t crowded enough, then the prodigal son shows up in an unexpected display of filial devotion to take care of his parents (Denny may or may not have been kicked out of his previous place of residence). Denny’s insistence that that Stem isn’t a “real” Whitshank – he came to live with the family as a toddler under quasi-legal circumstances – as well as Denny’s penchant for disappearing for years at a time if someone says something critical combine to render his siblings cross-eyed with rage.

In a phone call that catalogs years’ worth of disappearances and frozen shoulders, his sister Amanda finishes with a cry any "good kid" can relate to: “But most of all, Denny, most of all: I will never forgive you for consuming every last little drop of our parents’ attention and leaving nothing for the rest of us.”

As if the present didn’t have enough family drama to fill a decade’s worth of holiday dinners, Tyler then travels back to 1959, when Red and Abby were young, and then to the 1930s, before Junior builds the house on Bouton Road. There, Tyler upends expectations about the power dynamic in the Whitshank family, as well as waging an epic and almost-wordless battle over the color of a porch swing.

The sections set in the past represent a change for Tyler. It's a departure that offers its own rewards at the same time that it takes away from the siblings’ stories. Tyler was never one for wrapping plots up in a tidy bow, and certain characters remain mysteries.

But the ending is vintage Tyler – one that offers the hope of forgiveness that runs throughout her work with the calming brightness of a blue thread.