"If You Find This Letter" tells of the woman who writes love letters to strangers

“Stranger or not, we all need the same kinds of reminders sometimes. You’re worthy. You’re golden. You’ve got it.”

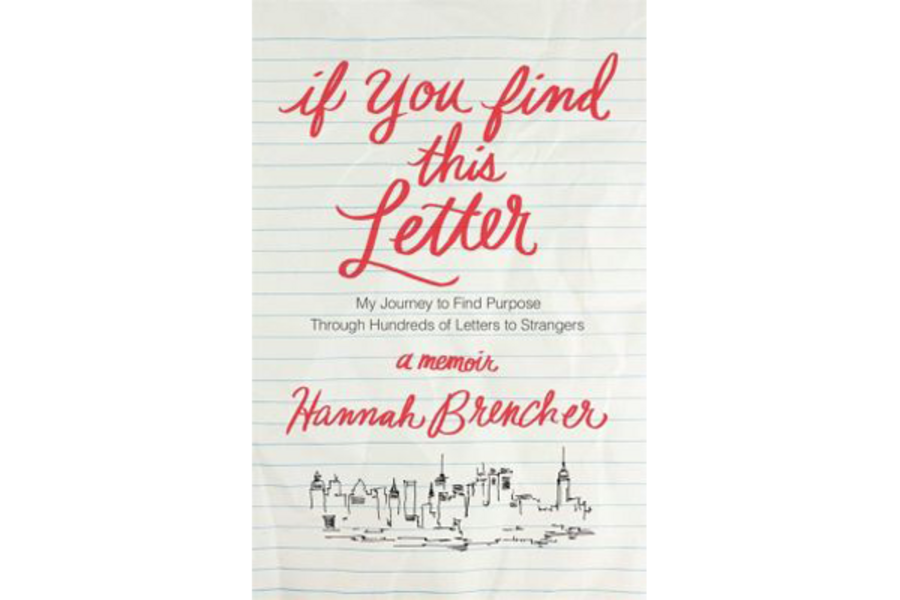

It’s this idea that inspired Hannah Brencher, author of the memoir If You Find This Letter: My Journey to Find Purpose Through Hundreds of Letters to Strangers, to start writing love letters to strangers.

"If You Find This Letter" tells the story of Brencher’s first year out of college, newly minted and aching to find purpose in the world. The memoir follows Brencher through her year of service in the Bronx, where she works part-time for the United Nations and volunteers at a local community center, all the while struggling with loneliness and depression and faith, and trying to find connection to the people around her.

It is in the midst of this first year in the “real world” that Brencher feels inspired to write letters to the strangers around her – the ones sharing the subway with her, the ones sitting at the coffee shop table next to her, the ones who look just as lonely and in need of love as she is. After offering on her blog to write love letters to anyone who needs a pick-me-up, Brencher goes all in, writing the letters were to become the beginning of More Love Letters, the organization Brencher founded that sends people all over the world encouragement and love in the form of handwritten letters.

Told using flashbacks to college and Brencher’s childhood, the memoir first and foremost sets up the most important person in Brencher’s life: her mother, a woman who planted the seeds of letter writing while her daughter was growing up. “I am the product of my mother’s bread crumb trails of love letters,” Brencher notes, describing one of the hundreds of letters her mother wrote her: it was a love letter left on her dashboard the day Whitney Houston died. And I will always love you, it read.

Knowing this, it’s not surprising that Brencher’s first instinct, when seeing her own loneliness and exhaustion mirrored in the eyes of a woman on her same train one night, was to pick up a pen and write to her. “Do me a favor and know the truth: You’re worth it. You are absolutely, unbelievably worth it and you were made for mighty things,” she writes.

It’s this moment that kicks off Brencher’s project of writing letters to strangers. Soon, Brencher is asking her blog readers if they need a letter, and if so, to email her. Just hours later, requests start pouring in – many being from people her own age.

“We were the entitled ones,” she says of the expectations the world, in 2010, had or millennials. “Self-absorbed. Impatient. Flighty. At the same time, seeing my inbox clogged with the email handles of Ivy League schools, I couldn’t help but think we weren’t all that bad. From the looks of the stories, we were trying. We were young and doing the best we could with what we’d been given.”

There were people like Laney, a girl who wrote to Brencher that she hated herself.

“The cutting came from hating herself. The vomiting came from hating herself. The abuse she accepted and claimed as something she deserved came from hating herself,” Brencher says. “There were dozens of Laneys living in my inbox.”

It’s stories like Laney’s and the other letter requesters that stick with us throughout the book, and that we want to hear more of. It is in these sections that Brencher jumps off the page and into our hearts.

If there’s one thing that is true about Brencher, it is that she’s lovable. She is the every woman – or at least the every millennial. She’s a girl struggling to find her way. She hardly knows what she wants, or what she’s capable of. She just knows she wants to matter. She grew up being told she could do anything and imagines that whatever it is, it will be “loud” and “noticeable.”

“I pictured fireworks,” she says.

Didn’t we all?

As she begins to receive letter requests, to write these letters, to quietly send them via snail mail to recipients she may never meet or hear from again, she begins to realize that a mark can be made with quiet acts too.

It’s an inspiring story, one that sets Brencher aside from the rest. She saw the world was in need of more love and she did something about it. But I wanted to hear more about that side of the story – the letters and the requests. Instead, much of the memoir is devoted to Brencher’s search for God, a puzzling theme of the book given its omission from the memoir’s book jacket.

It’s true that Brencher flies off the page when she’s pondering faith and God, when she prays. You can almost feel her heart lurching when she sends up her prayer: “Use me. Find me. Show me. Meet me. Please, just don’t forget me.” It is easy to recognize and empathize with Brencher’s desire for purpose, her hope that there is a larger meaning to life, the draw she feels at the thought of being a part of a congregation she can call home.

But that isn’t necessarily to say that non-believers will enjoy reading about Brencher’s journey to faith. I suspect that many will not, especially because the book's cover and jacket offer no hint that this is where the story is going.

Another off putting thing about "If You Find This Letter" is the distance that Brencher sometimes places the reader at. While she is not afraid of sharing her search for faith, her breakups, and her almost commitment to a religious cult in college, there is one topic she is tight-lipped on: her depression.

We learn, offhand and generally from a distance, about Brencher’s depression. “I just don’t want you to think that crying every afternoon at two p.m. is a normal thing,” a therapist tells her, revealing to the surprised reader that, a quarter into the book, that Brencher was struggling so much. In another chapter, Brencher brings it up herself, reminding us, “I still struggled to get up most mornings and I still cried.… For reasons and for no reasons at all. I worried the tears might never stop.”

These small reminders, peppered here and there, are a constant surprise. Brencher does frequently mention feeling lonely, but despite the dark stories that flow into her inbox, she hardly ever explains how hard and how badly she really felt those days. Many a memoirist has left out certain people or events in their lives, but it is frustrating that Brencher leaves out this part of herself. It makes us cognizant of the disconnect between the Brencher in real life and the Brencher on the page. Perhaps had she offered an explanation of why she doesn’t talk about it more, it would make more sense. But she doesn’t, and I’m left wondering why.

By the end of "If You Find This Letter" – at which point More Love Letters has been born and churning for a few months – I wished the book had delved deeper, all around. I loved the idea of writing love letters to strangers. I loved the connection that Brencher had with the world. I loved the depth of her emotion. It was impossible not to admire Brencher, and how she’d galvanized people worldwide to connect with others, to show love to strangers. She wasn’t too afraid to try to make a difference.

I wanted Brencher to bare herself – depression and feelings of inadequacy and all – so that I could truly understand the depth to which letter writing saved not only the people who read them, but maybe also herself.

Nevertheless, Brencher will make you laugh. Her turn of phrase, and the letter requests will make you cry, and the idea behind More Love Letters will restore your faith in your fellow humans, if it is waning. It will remind you that love is strong, that strangers can be full of love for you, and that, most importantly, we are not alone.

“It feels like, at the core, most of us are good,” Brencher writes. “And we want to be better…. We doubt ourselves. We celebrate. We drink too much. We laugh too little. We fall hard…. It’s a lot of 'we'. A lot of 'we' combating all the times I ever closed myself off and said, 'I feel so alone in this. I feel like no one knows what I am feeling.'

“It turns out we do, more often than we don’t.”