'Odysseus Abroad' views 'heroism' in the Age of Thatcher with gentle irony

Loading...

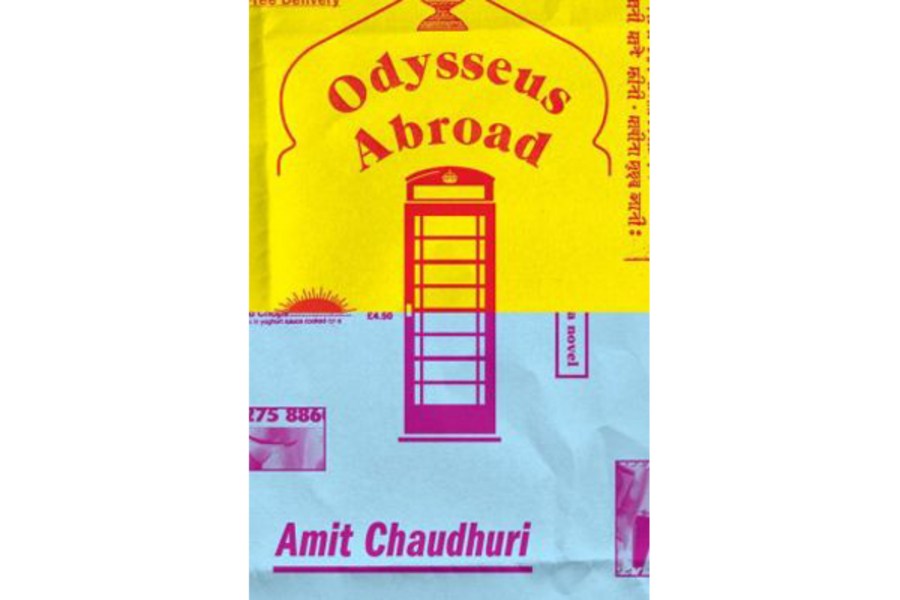

The title of Amit Chaudhuri's new book is Odysseus Abroad, and it has chapters like “Bloody Suitors!,” “Telemachus and Nestor,” “Eumaeus,” and “Ithaca” as further echoes of Homer's epic. In that epic, the easy return of Odysseus from Troy is thwarted by Poseidon, and he endures 10 years of adventures featuring sensuous sorceresses, lovestruck nymphs, and bloodthirsty cyclopses.

In Chaudhuri's gentle and wistfully ironic novel, our hero, 22-year-old Indian-born man named Ananda, wakes up on an average day in his 1985 London studio apartment and thinks about his recurring out-of-pocket expenses: lunch, dinner, books, and pornographic magazines. Odysseus navigated the Scylla and Charybdis and voyaged to the Land of the Lotus-Eaters; Ananda is working up the energy to travel a few stops on the Tube to visit his uncle Radhesh. The implied contrast between the Age of Heroes and Age of Thatcher is both light-fingered and, in its own way, mercilessly funny.

But like Odysseus, young Ananda often feels like “an exile in his home.” He's a would-be poet whose parents sent him to university in London, where he dreamed of achieving literary greatness (“Already a poet in his own eyes,” we're told, “Ananda, at fifteen, had judged Keats by the standards of his own subjectivity, and found him a little – bland”) and instead ended up a somewhat hapless dreamer adrift in 1980s London, dealing with noisy upstairs neighbors and a persistent homesickness that vaguely embarrasses him. He longs for connectedness with the busy, well-meaning Londoners all around him but lacks the confidence to create it.

One anchor of his existence is his weekly visit with his uncle, a seedy, strangely charismatic bachelor who's lived a virtually friendless life in London for decades. Ananda and Radhesh get on each other's nerves, we're told, although they'd “grown fond of the frisson” – in reality, they calm each other's loneliness by periodically spending a day together, getting lunch and sounding each other out for conversation (“specifically,” in the case of Radhesh, “for someone to be present, listening and nodding, as he talked”).

"Odysseus Abroad" is exactly half-way through its modest 200 pages before Ananda even reaches his uncle's basement bedsit in Belsize Park; Chaudhuri is in no hurry. This is a meditative novel, curling and uncurling around its various digressions like steam in a sauna. When chuckling over a repeat of the popular UK TV show "Rising Damp," Ananda describes the lead actor as “exuding an obtuse grandeur,” and the phrase could easily describe the book itself.

There are lovely little descriptive moments, like when Ananda calls Bombay from a payphone on his street and hears his mother's “clear childish voice reaching him after a delay, like a benediction.” And there are biting asides, as when Ananda reflects on his status as a “black” – that is, “the convenient catch-all en masse term for those not from Europe." (Chaudhuri sarcastically adds “The Greeks, responsible for European civilization, only barely escaped the misnomer by virtue of being lightly tanned”.) But the whole thing is far more about the journey than the destination.

The destination in this case is a day spent with Uncle Radhesh, and Chaudhuri resists any urge to raise that day above the quotidian. The two men get some lunch (Ananda is a bit embarrassed, as usual: “His uncle didn't know how to whisper, and he said in Bengali: 'There are places I know where you can get a cup of tea and an excellent cheesecake for half the price'”) and talk about family and literature in grooves worn smooth with repetition. Radhesh extols the virtues of great Bengali author Rabindranath Tagore – “He created not only a great body of work but a generation.… can you say that of another poet?” And Ananda has his inner responses ready, though he's too polite to voice them: “Tagore was hardly remembered.… And to be a Bengali in London meant being the owner of a Bangladeshi restaurant. What a joke, what a come-down!”

Racial and cultural tensions bubble under the surface. Ananda's uncle is missing a front tooth from a confrontation with some skinheads, for example, but this and other incidents like it are bubble-wrapped in anecdote to blunt their edges (“As a rule, his uncle avoided making eye-contact with skinheads, because it was unsettling to look at a visage that had no facial hair,” Ananda thinks, in a cyclopean echo, “Like looking at a face that was all eye: a giant angry eye”). There are no real gods or monsters in this stylish novel; instead, it's a low-key study of alienation, delivered with Chaudhuri's signature intelligence and reserve.

And its riches repay re-reading in, come to think of it, a very Homeric way. “One doesn't go to the epic to learn the story,” Ananda observes, paraphrasing Brecht, “but for the pleasure of hearing it again.”