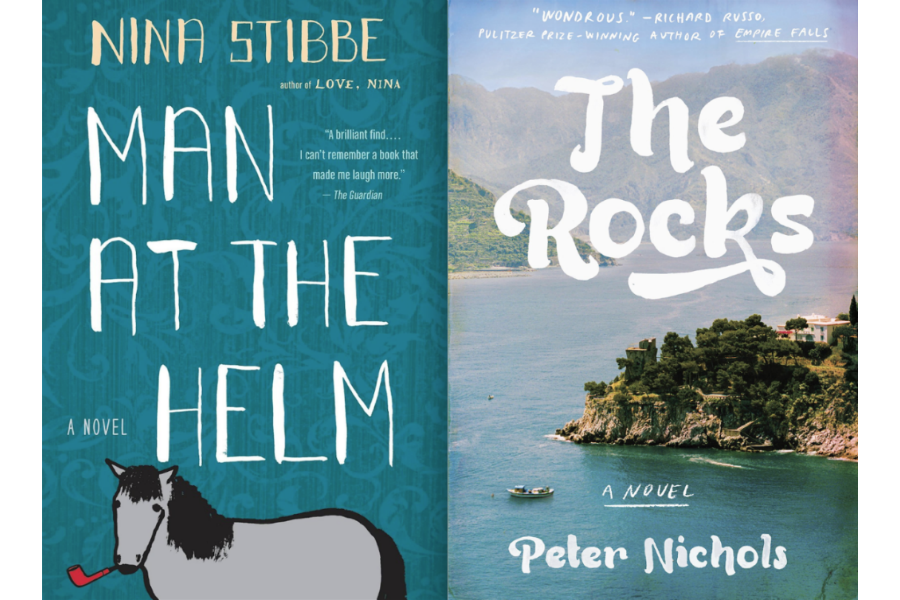

Pleasure Cruise: Two Summer Reads

Loading...

The annual spate of lists and listicles of summer reading has pretty much petered out and yet, officially speaking, summer has scarcely begun. Here, then, are two novels that exactly fill the season’s indefinable requirements. The first, Nina Stibbe’s Man at the Helm, is a novel so funny and engaging that it has taken a place in my own list of Top Books: Comedy Division. The second, The Rocks, by Peter Nichols, an accomplished sailor and author of a number of seafaring works, is a summer book par excellence. It is set on the sunny Mediterranean and constitutes a puzzle whose disassembled parts click, one by one, into a satisfying, coherent whole.

Man at the Helm is Nina Stibbe’s first novel and follows her splendid epistolary memoir, "Love, Nina: A Nanny Writes Home", an account of living in the home of the editor of the London Review of Books, Mary-Kay Wilmer, and her two sons. While there, the young Stibbe worked on and off on a novel based on growing up with her siblings and divorced, distraught, upper-middle-class mother. It was a work that the playwright Alan Bennett, a frequent visitor to the house, thought had real promise. Now, decades later, that promise is marvelously fulfilled.

It is the early 1970s and Lizzie Vogel is nine, the middle child between an eleven-year-old sister who is a font of responsible ideas and a young brother, Little Jack, who has a stammer and is devoted to factual information. Their parents have separated — Mr. Vogel has fallen in love with a man called Phil, though he subsequently marries a pear-shaped woman. Mrs. Vogel, the three children, and their dog, Debbie, move to a village in the English countryside, where they find they are pariahs because of the Vogels’ divorce and because certain old villagers had been evicted from the house they now own.

Within the house, squalor takes hold as Mrs. Vogel — who is accustomed to domestic help and is, in her words, “temperamentally unsuited to housework” — sinks into tumblers of whiskey, pharmaceuticals, playwriting, and depression. It is a situation that Lizzie’s sister warns will lead to the children being made wards of the court and put in the care of people who will pinch them and feed them nothing but spaghetti and crackers. The problem, in short, the older girl explains, is that the family lacks a “man at the helm.” How to supply one? Putting their heads together, the girls decide to write to men in the area as if they were their mother, inviting them over for drinks, hoping “that it would lead to sexual intercourse and possibly marriage.”

The sisters draw up a “Man List,” though that itself is not without its vexations. Lizzie reports:

I’d always known my sister was pretty much the boss, but I thought there was an understanding that we both had to agree before any man was added.

Mr. Nesbit was an oldish man with a full beard who had apparently once lived in a section of our house. He often sat on the street bench almost opposite, sucking Nuttall’s Mintoes, shouting out about the Suez Canal and inviting children to knock on his wooden leg.

Looking at the Man List one day, I was surprised to see Mr. Nesbit’s name had been added without prior discussion, albeit with a question mark. . . .

“Why have you added Mr. Nesbit to the list?” I asked, hoping it might be a different Mr. Nesbit, a doctor in the next village or something.

“Why not?” she said.

“You mean to say it actually is the Mr Nesbit?” I said. “He’s virtually a tramp.”

“He’s a war veteran, Lizzie,” said my sister. . . .

“Mum would never cope with the wooden leg,” I said.

“She’d bloody well have to get used to it,” said my sister, sounding very cross. . . .

“No,” I said, “he’s temperamentally unsuitable for the helm.”

I felt uncharitable but very sensible. We couldn’t have someone on the list who habitually shouted, “Get off and milk it,” as we rode past him on our ponies. Plus, how could we work together if she could act in that unilateral manner? Not that I would have used those words at the time. Obviously.

The mission proceeds over a period of about two years, a time replete with unfortunate episodes and the daily trials of the “feral and manless.” There is excitement, too, and a foul plot is foiled. All are detailed by Lizzie, a stickler for accuracy, a practical thinker, and a young student of human behavior. Her voice is one of the hardest for a writer to pull off: the ingénue. Literature is deformed by instances of hideous cuteness in this area, but Stibbe’s rendition is restrained, tart, and perfectly paced. She manages to convey a young person’s dismay at disorder and pleasure in the organizing force of language. Thus, for instance, Lizzie embraces the decisiveness of the word imperative and the hedging utility of the expression “not as such.” Further, her descriptions of people and events often include a maverick fillip at the end, as here: Her maternal grandmother, she tells us, is “a prickly woman . . . who seemed to like making people feel bad about themselves, which was easy with our mother who had failed at marriage, had two abortions and a miscarriage, a drink problem, an addiction to prescription drugs and who, for some reason that I can’t explain, had a habit of storing stemware upside down in the cupboard — a thing which always infuriates the well-bred.”

I simply hugged myself with joy reading this book, for the tale it tells, which is funny, painful, and ultimately happy, and above all for the voice, which is perfection.

"The Rocks" of Peter Nichols’s The Rocks is a small hotel on the island of Mallorca in the Mediterranean Sea. It has been owned since 1951 by a woman called Lulu, whom we first meet in 2005 at the book’s beginning — shortly after which she plunges into the sea, to her death, in the arms of Gerald, her first (ex-) husband, whom she has despised for almost sixty years. With that, two more characters bearing a mysterious grudge against each other show up: Luc, Lulu’s son by her second (ex-) husband, and Aegina, Gerald’s daughter by his second (late) wife. They have come to deal with the deaths of their respective parents but leave the reader with further questions. The answers to these emerge gradually as the novel travels back, step by step, to 1995, 1983, 1970, 1956, 1951, and 1948. Each one of those years gives rise to a tale, all of which are steadily and deftly woven together, until the story circles back to 2005, putting one last little piece in order.

Present at the heart of the book is the story of Odysseus: Gerald’s claim to an extremely modest fame, is as the author of "The Way to Ithaca", published in 1951, in which, in a series of voyages, he follows what he speculates to have been Odysseus’ journey from Troy back home. A couple of the incidents in the book echo Odysseus’ trials, and all of the more dramatic events have a raw Homeric tenor: a little sailing vessel is attacked by a piratical band; a man falls from a boat to drift alone and abandoned in the sea, a fifteen-year-old boy is seduced by a seventy-year-old woman; a fifteen-year-old girl is ravished/ravaged by a raddled adventurer; there is even an escape from a cave courtesy of a flock of sheep; and all the while the ancient Mediterranean sun blazes down on acts of duplicity, despoliation, and daring. This is a wonderfully rich novel — its characters are numerous and vigorously alive, its sense of place, on land and at sea, is brilliantly realized, and the plot is cunningly paid out and made fast by a masterly hand.