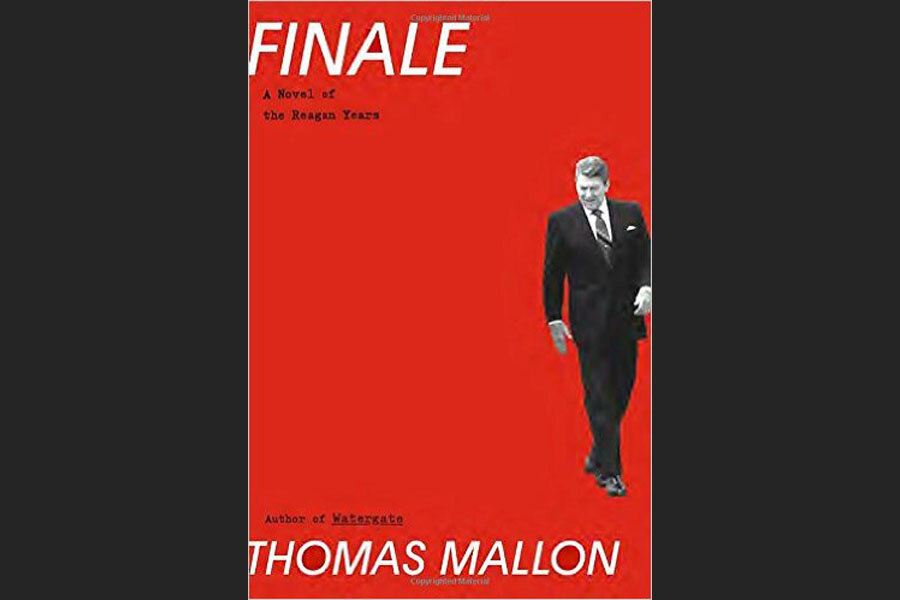

'Finale,' set in the Reagan years, confirms Thomas Mallon as a master of political theater

In September 1986, establishment Washington gathered at the National Cathedral for a memorial service for Averell Harriman. LBJ’s widow, Lady Bird Johnson, attended, as did the soon-to-be next First Lady, Barbara Bush. New York Gov. Mario Cuomo paid his respects, as did Secretary of State George Shultz. So, too, did Supreme Court Justice Thurgood Marshall and the Kennedy family’s Boswell, historian Arthur Schlesinger Jr.

Harriman, as both his résumé and his memorial’s invitation list showed, knew just about everyone of consequence in 20th-century American politics. During his lengthy career, Harriman served one term as governor of New York in the mid-1950s, a term sandwiched between many years of high-ranking diplomatic posts in Democratic presidential administrations.

The New York Times declared Harriman “the American plenipotentiary supreme” in his obituary. Under FDR, he presided over the lend-lease agreement, a role that put him in close and frequent contact with Winston Churchill. Later, President Truman handed Harriman a prominent role steering the Marshall Plan.

Thomas Mallon takes this human clay and, after adding a dash of inspired inner dialogue, sculpts characters who embody the folly and frustration of political power. And, for good measure, Mallon’s characters never forget the striving required in the struggle for continued relevancy. In Finale, a novel set in the late-Reagan era, Mallon’s account of Harriman’s memorial includes ambling into the mind of political essayist Christopher Hitchens. In his late-30s and fearless in his opinions and critiques, Hitchens glances at Sen. Ted Kennedy of Massachusetts. Hitchens observes Kennedy is “alarmingly fat and mottled of complexion” as he watches the senator “waddle past the pew.”

Kennedy, as in the real-life memorial, says of Harriman, “He gave us his help and his heart in our happiest days and harshest hours.” Mallon’s minor novelistic edits to the actual statement – “He was an adviser and counselor, who gave us his help and his heart in our happiest days and harshest hours” – allows him, in mind of Hitchens, to render this observation: “Pity anyone near Teddy’s Cutty-Sarked breath during the delivery of all those aspirated aitches.”

Mallon has become a master of such political theater, mining Washington in novels loosely defined by Lincoln’s assassination, Truman’s unexpected defeat of Thomas Dewey in 1948, Watergate and, in “Finale,” the Reagan years of AIDS, Iran-contra, and nuclear negotiations with Mikhail Gorbachev and the Soviets in Reykjavik, Iceland.

What makes Mallon’s novels so much fun is the author’s blend of historical exactitude with imagined reactions and machinations. Many of those machinations play out in the plausible guise of fictional secondary players. In 2007, Paul Morton, in an introduction to a feature interview with Mallon, noted his “novels tend to center on the Rosencrantz and Guildensterns of the American past.”

That they do, including encore appearances by two characters from Mallon’s 1997 novel, “Dewey Defeats Truman,” in “Finale.” Anne Macmurray, now a liberal activist protesting Reagan’s “Star Wars” anti-missile program, and her ex-husband, Peter Cox, a Republican fixer, have gone on from Dewey’s Michigan hometown to become constant, if minor, players in national politics.

Mallon puts them to effective use in his new novel, along with a fictional, bewildered Reagan aide named Anders Little.

Mallon fits all of these pieces together, combining broad historical accuracy and fictional verisimilitude with aplomb. Characters historical and fictional alike display bonfires of vanities, and insecurities, galore.

Pamela Harriman, Averell’s influential and oft-married widow, takes several star turns with Hitchens in Mallon’s novel. A real-life doyenne of social climbing in Washington, she, too, inspires the novelist to share fictional, punchy asides.

During a meeting with three Democratic senators (Daniel Patrick Moynihan, Fritz Hollings of South Carolina, and Tennessee’s Al Gore), she laments the presence of Louisiana Congresswoman Lindy Boggs, who’s accompanying Moynihan, and the Southern senators’ wives.

“Tipper (Gore), Peatsy (Hollings) and Lindy! Dear God, it was like some Faulknerian version of Winnie-the-Pooh,” Pamela Harriman thinks, in Mallon’s gleeful words.

The author’s rendering of Nancy Reagan obsesses over the chances of another assassination attempt, simmers at what she regards as the dithering of chief of staff Don Regan, and avoids, as much as possible, constant family tension with the adult children: Maureen Reagan, Ron Reagan Jr., and Patti Davis.

Mallon gambols across the rich and uncertain terrain of the First Lady's constantly consulting astrologer Joan Quigley for signs of presidential peril. Throughout the book, Mallon imagines the repartee of talk-show impresario Merv Griffin as he soothes Nancy Reagan’s insecurities.

Reagan remains inscrutable, confounding his real-life biographer, Edmund Morris, as well as his aides, family members, fellow politicians, and Gorbachev. No one can read the president, who seems detached, oblivious, charming, strategic, and bizarre, often within the span of a single conversation.

Routine political duties – the Reagans attending the opening of the Jimmy Carter’s presidential library come to mind – become sublime in their ridiculousness, and, of course, Mallon’s wry observations. Nancy ruminates on what she regards as the former peanut-farmer’s provincialism (she hates the way he casually signs letters “Jimmy”) while Carter himself fumes when he see Walter Mondale, Carter’s former vice president, and the man Reagan crushed in the 1984 election, heaving with laughter as Reagan trots out boilerplate one-liners.

Richard Nixon, another president whose psychology still baffles historians, makes several delightful appearances here, too. Mallon bookends his main story, set in 1986, with scenes from the GOP conventions in 1976 and 1996.

In the first, Ronald Reagan seems to have lost any chance of a presidential nomination. Nixon, watching on TV at his California home, scoffs as Gerald Ford’s running mate speaks. “That poor battle-mangled Bob Dole would soon be building wheelchair ramps for the disabled all over America. This was the sort of penny-ante stuff that had always bored him while he governed the country,” Nixon reflects.

Twenty years later, Nancy Reagan speaks to the nominating convention for, yes, Bob Dole. Ronald Reagan reigns as a Republican deity at this point, but watches from his from California home, gripped by Alzheimer’s.

“For a moment,” Mallon writes of Reagan watching TV, hearing his wife speak to the delegates, “he isn’t hearing the box at all, but his attention comes alive once more when she, the woman whose red dress it was, begins to talk of a shining city on a hill.”