'Living On Paper' wonderfully displays the many faces of Iris Murdoch

Loading...

It's likely that many 21st-century readers will associate Iris Murdoch with Alzheimer's disease, and the reason for that will be clear: In 1999, Murdoch's husband John Bayley published "Elegy for Iris," in which he describes the struggles of her final years in eloquent, absolutely heartbreaking detail.

The irony of course is that this was the opposite of Bayley's intention; regardless of its title, his book was intended to be at least as much a celebration of his wife as a memorial to her. In its pages, we see Bayley fall instantly in love with the long-legged young woman he spots bicycling at Oxford; we see him court her (“Perhaps it's time we made love,” she informs him at one point, with typical breezy authority); we see with crystalline compression all the years of their marriage; and we see his occasional frustration with her changeable, off-kilter ways. Referring to the Greek myth in which Hercules grapples with a famous shape-shifter, she at one point tells Bayley, “Just keep tight hold of me and it will be all right.”

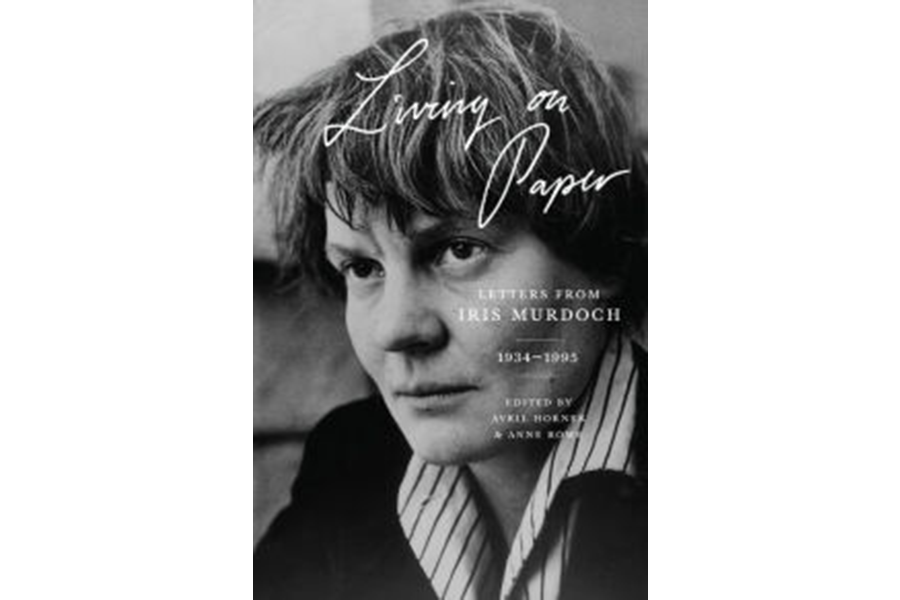

It wasn't always possible to hold onto her in Bayley's pages. He often digressed into self-pity, and even through his adoring perspective, it became obvious to readers that there were many Iris Murdochs, and that he was only married to one of them. He tells us that she wrote thousands of letters, that she spent four hours a day on them, and in a big new volume of those letters from Princeton University Press edited by Avril Horner and Anne Rowe, readers come closer to Iris Murdoch – the writer, the friend, the lover, the person – than either Peter Conradi's official biography or Bayley's memoirs allowed. In Living on Paper: Letters from Iris Murdoch, 1934-1995, we get a relatively small sampling of the vast correspondence she kept up, and through those letters, we glimpse as many of those other Iris Murdochs as we're ever likely to see.

“Unlike biographies,” Horner and Rowe write in their refreshingly frank Introduction, “which usually offer coherent portraits of their subjects, letters provide a kaleidoscopic picture, their authors sometimes responding in remarkably different ways to different correspondents, even on the same day.” Iris Murdoch was an extremely kaleidoscopic personality, keeping friends from other friends, compartmentalizing not only different people but different parts of her own personality, and thus underneath its chatty, bookish surface, "Living on Paper" is a slightly dizzying reading experience.

At nearly 600 pages, it's a generous enough selection even for being such a thin sliver of the whole. Critics will tend to concentrate on the salacious bits, and thanks to the omnivorous sexual appetites of the author's youth, there are plenty of such bits. Murdoch was an enthusiastically passionate person who had a penchant for infatuating herself with emotionally unavailable older men like Elias Canetti or Raymond Queneau, and she could be equally ardent in her addresses to women. Writing to fellow author Brigid Brophy in 1966, for instance, she melodramatically warns that her husband knows of their correspondence and is “on the brink of being jealous of you,” and there are hushed stage whispers like this throughout the book's first half.

Such improbably steamy elements shouldn't be allowed to overshadow the book's subtler but more genuine charms, however: This is foremost the multi-faceted portrait of a terrifically alive mind. It will come as no surprise to readers of her novels that Murdoch is hopelessly enamored of language; “I need pavilions and pavilions of talk,” she writes to Philippa Foot in 1969, and a decade later she's still urging, “Do communicate (best by 9p letter) when you get this.” And everywhere there's a very droll, very appealing humor – as when she writes in 1981 to update a correspondent on the latest news about Princess Diana: “[She] became very unpopular in the autumn because she (how can they have let her do it?) shot a stag. However she is now popular again because she is pregnant. (She and the prince are both descended from Henry VII so it must be OK.)”

Romantic obsessions notwithstanding, it's this Iris Murdoch – compulsively discursive, doggedly happy – who dominates "Living on Paper" and fills it with the kind of smart, nimble-footed smalltalk that is always the principal joy of reading letter collections. When she writes to Michael Oakeshott in 1958 about having Meniere's disease, “a tedious and quite incurable ear ailment” that also afflicted Martin Luther, Jonathan Swift, and Jean-Jacques Rousseau, she deadpans: “All irritable bad-tempered men. Perhaps I shall get like that.” But she never does.

Reading the last of these letters, the ones dating from the mid-1990s, it's impossible not to be thinking of the fast-approaching final years. She felt them coming too and described them to her biographer as “sailing into the darkness.” "Living on Paper" shows us, more clearly than ever, the remarkable person that darkness swallowed. That's the sadness of the book, but that's also its great gift.