'Everyone Behaves Badly' chronicles the rise of Ernest Hemingway

An old saw tells authors to “write what you know,” a rule that’s thankfully breached by novelists who’ve never actually encountered a fire-breathing dragon or poisoned a dowager in the drawing room.

But sometimes what authors know is exactly what readers need: a slap of barely disguised reality, well remembered and well told, without the frills of excessive imagination. A roman à clef, literally a novel with a key, one that unlocks a door to real lives. And if it wrecks a few of those lives in the process, well, masterpieces don’t come cheap.

Wrecked lives? Ernest Hemingway, this one’s for you. To great effect, and a great cost, he perfected the art of burgling life stories by creating a legendary novel out of the true stories of his fellow travelers in the Lost Generation.

The origin story of “The Sun Also Rises,” as masterfully told by journalist Lesley M. M. Blume, reveals the complicated sides of the young Hemingway: brilliant and vicious, arrogant and ambitious, an obsequious charmer and a jerk of the highest order. Like his characters and those of frenemy F. Scott Fitzgerald, he’s also a man prone to destructive carelessness.

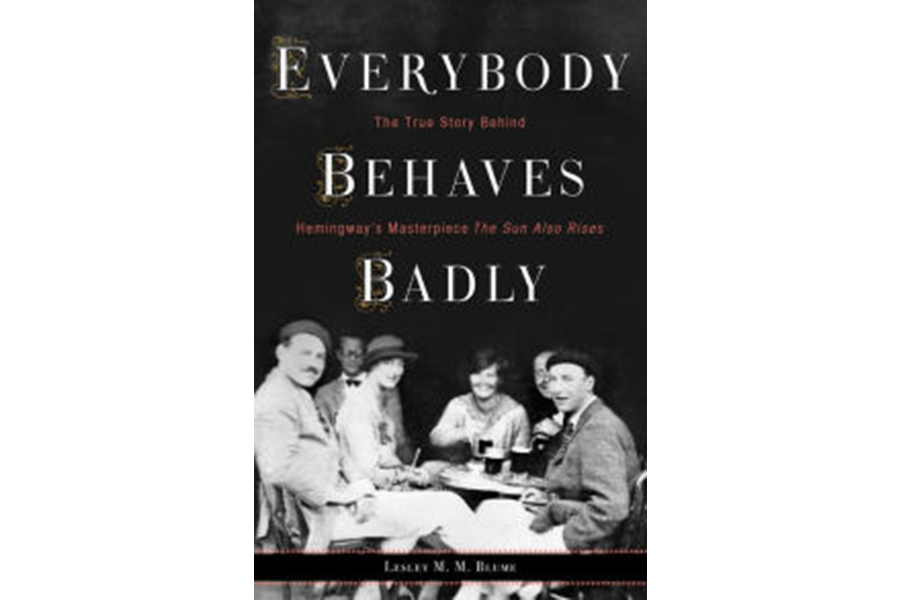

Blume, who’s written previously about literary icons and the culture of the past, brings the nearly forgotten Hemingway of the early 1920s to vivid life in Everybody Behaves Badly: The True Story Behind Hemingway’s Masterpiece ‘The Sun Also Rises.’

The story of the always-hustling, sometimes-desperate Hemingway in Paris doesn’t fit into the narrative of his various better-known identities as hard-living, hard-loving, and hard-everything-else-ing. This was before he was famous, Blume writes, when Hemingway “played one of his earliest roles: unpublished nobody.”

In his aggressive quest for success, Hemingway schmoozes the literary lights of Paris and lives in poverty with his devoted wife and baby when her trust fund money disappears. He’d turn on his wife and many of these pals later, but not quite yet. For the moment, he needs them, and they like and love him.

Early on, Hemingway writes a 183-word vignette about a bullfight; he’d never seen one. That would change. Soon he develops his famous lifestyle. He goes fishing, runs with the bulls, dines with the ex-pat swells who wash up on the Left Bank. And he listens with what his son would call a “rat-trap memory,” an image that appropriately evokes a piercing snap, snap, snap!

Then along comes “The Sun Also Rises” with characters and their backstories pilfered from the tumultuous and tortured lives of his friends. Even the soon-to-be-famous words “Lost Generation” are borrowed, with credit, from Gertrude Stein, who’d become yet another enemy with time. And the title itself comes from the Bible.

With wartime over, at least for the moment, the literary lights of 1920s Paris and Manhattan don’t yet fight for their lives or grand causes; their deadliest weapon is a well-timed wisecrack. As a result, this tale never crackles with the excitement and tragedy of Amanda Vaill’s masterful 2014 look at Hemingway & Co. in “Hotel Florida: Truth, Love, and Death in the Spanish Civil War.”

Even so, “Everybody Behaves Badly” is deeply evocative and perceptive, and every page has a Hemingway-like ring of unvarnished truth. His reality is quite like the world of the novel, a place, Blume says, “where people aim to please themselves – even if their actions don’t bring them much pleasure.”

Blume gains invaluable insight by interviewing relatives and friends of the major players, including Hemingway’s onetime daughter-in-law. Letters and drafts are enlightening too. As his publishers cluck nervously, Hemingway excises a slightly naughty word or two, makes certain characters slightly harder match to real people (but not Jake Barnes, aka himself) and even improves upon the famous last sentence of “The Sun Also Rises.”

Saving readers from having to rush to Wikipedia, Blume helpfully provides an epilogue with updates about what happened to all of the real-life people who found themselves – without any warning – depicted in print. Several of his compatriots would be forever haunted by his callous and undisguised depictions of their lives.

For some, their personal excesses – too many spouses, too little happiness, too many drinks – would linger beyond the 1920s. A few in the group wouldn’t make it to old age, including Hemingway. One of his ex-pals declared he needed to demolish the love of his friends and, in the end, found there was “no one left ... to obliterate but himself.”

What if these real people had all treated each other, and themselves, with a bit more kindness? Could Hemingway’s mind still have created the timeless likes of Jake Barnes and Lady Brett Ashley?

Perhaps not. But to borrow a Hemingway phrase, “Isn’t it pretty to think so?”