'The Mistresses of Cliveden' transports readers into multi-generational drama

Loading...

For a time back in the 1970s, it was possible for interloping Americans to do something generations of marquesses and grasping British earls could only dream about. Those Americans – both students and their faculty and staff – could traipse around the rooms and 375-acre grounds of sprawling, magnificent Cliveden House in Buckinghamshire. The house, with its stunning gardens sweeping gently down from chalk hills to the Thames, was at the time being used as an overseas campus for Stanford University, and who knows what its American inhabitants knew of its 350-year history.

High-profile love affairs had been brokered in those gardens; rival courts had headquartered in those stately rooms; government-rocking scandals had begun around its swimming pool. Like so many great houses dotting the English countryside, Cliveden's calm, beautiful exterior belied its long and often uproarious past.

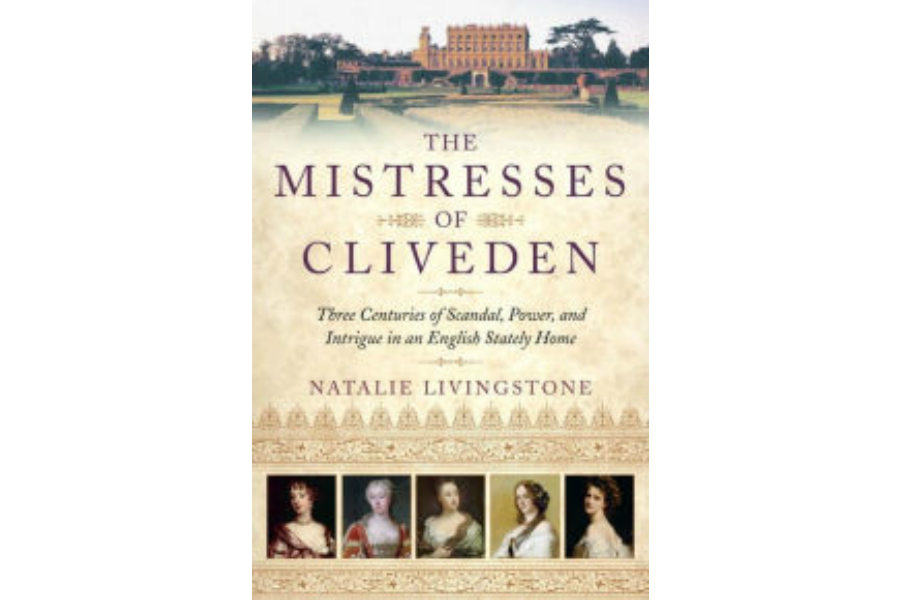

That past comes to life again in all its gaudy extravagance in The Mistresses of Cliveden by Natalie Livingstone, a look at centuries of life at Cliveden as told through the lives of five women who ruled the place at various stages in its long life, five chatelaines whose biographies Livingstone has combined into a marvelously readable story of Clivenden itself.

The story begins when George Villiers, Duke of Buckingham and childhood friend of King Charles II, saw and fell in love with the magnificent grounds of Cliveden in the 1660s. At the time, those grounds only housed a couple of small hunting lodges, but Buckingham was determined to make the place palatial.

He bought it from the Manfield family (keeping them on as stewards) and poured money into construction work over the next decade, with the main aim of creating an oversized trysting place for his mistress, Anna Maria Brudenell, whose husband, the Earl of Shrewsbury, he'd killed in a duel. Thus installed as the first chatelaine of Cliveden, Anna Maria ruled the house until the House of Lords ordered Buckingham to separate from her in 1674.

In 1696, the Earl of Orkney bought Cliveden, and his wife Elizabeth, who'd been a long-time mistress of King William III, came to be ruler of the estate, eventually employing the noted architect Thomas Archer to do extensive renovations that stretched until 1712. Seven years later, Princess Augusta of Saxe-Coburg, Livingstone's next subject, was born, and in 1736 she married Frederick, the son and heir of King George II.

Augusta, who had “never said a foolish thing nor done a disagreeable one since her arrival” according to Horace Walpole, added two aviaries and a flower garden to the grounds of Cliveden.Twenty years after she died, however, Clivenden burned down again in a catastrophic fire in 1795 and lay in picturesque ruins for two decades.

The task of restoring Cliveden to glory was taken up next by the fourth mistress of Livingstone's account, Harriet, Duchess of Sutherland. She was the granddaughter of the famed Georgiana, Duchess of Devonshire, and she and her husband, George Granville, the 2nd Duke of Sutherland, bought Cliveden in 1849 from George Warrander, who'd commissioned architect William Burn to do extensive work on the house – all of which came undone when Cliveden once more burned to the ground. This time, 1849, the house burned in a blaze so bright Queen Victoria could see it from Windsor five miles away. The Duchess, for whom Livingstone shows a quite clear affection (“Majesty came easy to Harriet,” she writes), was determined to rebuild.

The splendid inheritance of all that rebuilding eventually came into the charge of the fifth and last of Livingstone's chatelaines, Nancy Astor, who was “forthright and fierce” and who would later become the first woman to sit in Parliament. William Astor had given Cliveden to his son and daughter-in-law as a wedding present in 1906, and at the outbreak of the First World War, it was converted into a hospital for wounded soldiers, its glamor “for now, overlaid by the grit of modern war, the ornamental replaced by the functional.”

In the post-war years, the house played host to the Nancy Astor's infamous “Cliveden set,” and in 1963 it played a part in the “Profumo affair” that brought down the conservative government of the day. Even in Livingstone's boisterous account, however, it becomes obvious in these final pages that Cliveden has entered a relatively quiet old age.

The place was donated to the National Trust and is now a luxury hotel owned by Livingstone and her husband, who spend every day amidst the artful jumble of centuries, “where past and present are woven together: where 20th-century wiring runs underground along 16th-century tunnels, service bells from the 19th century hang from the wall above Wi-Fi boxes, and a swimming pool from the 1950s sits within a garden landscaped in the 1700s.”

Ballantine Books has given The Mistresses of Cliveden a suitably opulent design, with heavy-stock pages, rubricated chapter headings, and glorious full-color portraits of the five remarkable women who safeguarded a great house through fire, rebellion, plague, and war. Like Cliveden itself, it's nice to think those five have earned some peace and quiet at last.