'The Hello Girls' pays overdue tribute to a group of World War I heroines

Loading...

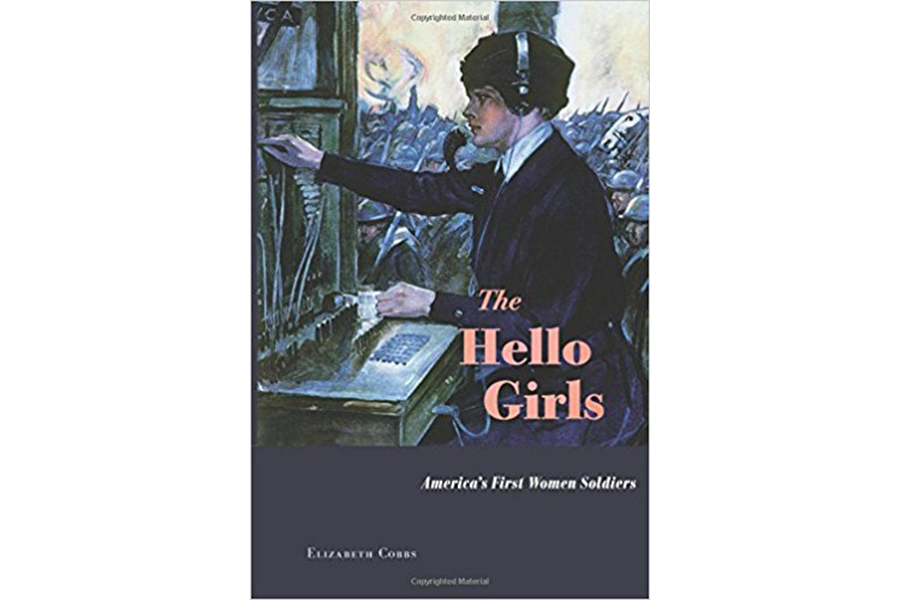

Elizabeth Cobb's utterly delightful new book, The Hello Girls: America's First Women Soldiers, tells the story of the small band of American women who traveled overseas with the doughboys of the American Expeditionary Force (AEF) to participate in World War I as “girl telephone operators” attached to the army's Signal Corps. It's a little-known side-story of the war, but it's not a little story: In Cobb's skillful handling, it becomes a big, multi-layered tale of courage and long-delayed justice.

Woodrow Wilson won his re-election in 1916 largely because of his steadfast assurances that he would not get the United States involved in the war currently being fought in Europe on the fields of France and Belgium. But by April of the following year, German warmongering and unrestricted submarine warfare in neutral waters had driven him to ask Congress for a declaration of war.

The country wasn't even remotely ready to fight its first foreign war in a century. Its tiny army, commanded by General John Pershing, barely formed a regiment; its navy was nearly nonexistent; its industry slumbered at peacetime levels. And one piece of technology that would later prove essential was still in its comparative infancy. Cobb quotes British historian John Terraine: “The chief instrument of generalship throughout the war was, of course, the telephone.… Only the telephone, the uncertain, temperamental telephone of the second decade, gave generals any real power of command.”

But those telephones weren't much good without trained and proficient operators, and the enlisted men initially assigned the task were noticeably lacking. What was needed was professionals, and at the time, 80 percent of AT&T's telephone operators were women: “Diligent and quick, the best of them efficiently manipulated cords and plugs while fielding requests for the time and other information.” Even before the Army could have application forms printed, more than 7,600 women inquired about the first 100 positions. Two hundred and twenty-three of these women would eventually operate Army switchboards in Europe. The so-called “Hello Girls” would become America's first female soldiers years before women could vote in America.

Cobb very adroitly weaves the story of the Signal Corps into that larger story of American women fighting for the right to vote, but it's the warm, fascinating job she does bringing her cast of "The Hello Girls" to life that gives this book its memorable charisma. We meet 25-year-old Grace Bunker, the “torchbearer” of the group; French-born and fully bilingual 18-year-old Louise LeBreton, who lied about her age in order to sign up; Hope Kerwin, the San Francisco native who wrote to the War Department promising to make herself “an awful nuisance” until they accepted her; Isabelle Villiers, already a yeoman first class in the Boston Naval Yard; Kansas native Merle Egan, “just the sort of person to show her grit in a patriotic cause – or any other campaign about which she cared;” [Inez Crittenden, whose civilian employer wrote her the kind of recommendation most of the Hello Girls had: “She is well educated, speaks French, is industrious, thoroughly reliable in every way, and capable of filling well any position she may apply for.”

They wore the uniform, endured the discipline, and did their job. And they met the reflexive rejection of their male colleagues with the flinty determination of trailblazers. When Hello Girl Merle Egan was sailing out of New York harbor, looking at the Statue of Liberty one last time, Cobb tells us she encountered a young aviator who pointedly asked her, “Why are you on this ship in that uniform?” To which she replied, “Same reason you are: I am on my way to France to help win the war.”

They won the respect of their peers – and of General Pershing, who'd believed in them from the first – but the saddening, frustrating final section of Cobb's story makes clear that they had a much harder time winning the respect of their government. After the war, the Hello Girls found little of the recognition they'd earned in Europe. “Female veterans typically discovered they were not soldiers in the eyes of their government – and thus the world – when they applied for something, whether treatment at an army hospital, membership in a veterans' organization, tax benefits offered by local municipalities, or the bonus granted to every soldier, sailor, marine, and nurse,” Cobbs writes, adding simply, “Surprise characterized their letters.”

The US government insisted, with the bizarre Catch-22 logic that tends to characterize bureaucracies, that since the law stipulated that all American soldiers were men, the Hello Girls couldn't have been soldiers – and so weren't entitled to any military benefits or recognition, despite the fact that they had signed up as soldiers, shipped out as soldiers, endured the service as soldiers, and come closer to the front lines than many of their male counterparts. They fought for years to gain the recognition they deserved as the forerunners of all women serving in the US armed forces. This terrific book pays them a long-warranted tribute.