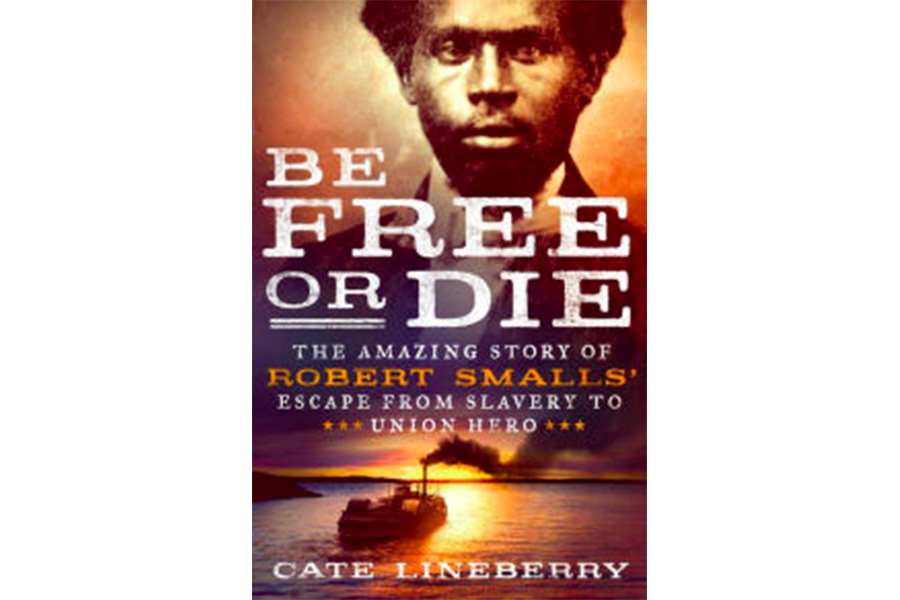

'Be Free or Die' profiles former slave and US Congressman Robert Smalls

Loading...

It was 3 a.m, on the foggy morning of May 13, 1862, in Charleston, S.C. The 147-foot-long, 30-foot-wide, dual-paddlewheel steamer Planter, owned by Charlestonian John Ferguson, but leased to the Confederacy for a tidy $125.00 per day, came chugging out of Charleston Harbor – the port through which passed approximately 40 percent “of all enslaved Africans who came to North America through the trans-Atlantic slave trade.” The vessel seemed to be off on one of its many transport or dispatch runs.

The Planter was fast and maneuverable, a most handy vessel for Confederate General Roswell Ripley. Ripley, in turn, had hired a private contractor, Charles J. Relyea, as captain. The captain, first mate, and engineer were white contractors, but the rest of the crew was made up of seven enslaved black men: Robert Smalls, wheelman (but don’t for a second call him a “pilot,” not a black man); John Small and Alfred Gourdine, engineers; and deckhands David Jones, Jack Gibbes, Gabriel Turner, and Abraham Jackson.

Smalls was a married man, with two children, and like all slaves, he lived in everyday fear that his family would be sundered according to the disposition of their owner. So Smalls put a plan in motion – a dire one, but these were dire times. Smalls had two aces up his sleeve: The white officers often left the vessel at night, an utter no-no, to visit their families, and Relyea would leave his distinctive, wide-brimmed straw hat in the wheelhouse. Smalls’s plan was simple: after dark, put on the hat and steal the boat. His chapeaued silhouette, he hoped, would help him avoid detection as he picked up various family members at a number of harbor points, ran the harbor’s batteries, including Fort Sumter, wove his way through the treacherous bars at the harbor’s mouth, and made contact with the Union blockade before they shot him out of the water.

Journalist Cate Lineberry tells this story in Cinemascope. So much could have gone wrong, and so much very nearly did – two of the commandeers finked out and might have scuttled the scheme if three other black men had not joined in: Abram Alston and Samuel Chisholm, boatmen; and William Morrison, tinsmith and plumber by trade. It is worth noting these names, for although Smalls concocted the idea, all the men and all their family members (women and children locked below decks so that their fear would not bubble over and give the ploy away) effected the escape. The rest of Be Free or Die is devoted to the remarkable life of Robert Smalls.

Smalls’s story is dramatic enough, but Lineberry gives it greater honor by setting it in the context of its surrounding circumstances. It doesn’t take any particular imagination to understand that the Civil War did not erase the institutionalization of racism in this country or even, for that matter, end slavery. But it is mostly students of the period who appreciate the hurdles that African-Americans experienced at nearly every turn.

Lineberry goes deeper. She pulls apart Lincoln’s Proclamation of Amnesty and Reconstruction, which encouraged helping freemen gain education and work, but had no teeth to enforce compliance. Andrew Johnson had been Lincoln’s second vice-president, a move intended to gain the Democratic vote. But Johnson was a disaster as president. Lineberry portrays Johnson as a man eager to wield “his power over the Southern gentry, who he had railed against since his poverty-stricken youth.” He issued pardons only if “the wealthy personally appeal to him,” pardons that “would allow the planter elite to regain political control in the South.” Newly formed state legislatures created separate sets of laws for blacks, the Black Codes, “an obvious attempt to preserve slavery” in everything but name. If the Thirteenth Amendment was passed in 1865, the Fifteenth was not passed for another 15 years.

Through the institutional and the quotidian racial injustices, Lineberry threads the story of Smalls’s life. Yes, he was a Union hero, but he was also a black man. He would be denied ridership on Philadelphia’s streetcars; he would suffer every twist and turn of racism’s indignity. When he saved the Planter a year after his escape – the vessel taking heavy fire as it delivered provisions to Union troops, the white captain hiding in the steamer’s coal bunker – he was made a captain, but a civilian captain, not a military one.

Yet Smalls found his own path to dignity. He eventually bought the house he had once lived in as a slave. He lost a son to smallpox, but he saw a daughter born free. He served as a United States congressman for five terms. President Benjamin Harrison appointed him US Customs collector for the Port of Beaufort, another rarity, and a post he held for 19 years until “two white southern senators blocked his reappointment.”

One incident, in which Smalls was arrested and charged with accepting a bribe while in Congress, is uncharacteristically left to dangle. Smalls's appeal included the claim “that he was entitled to congressional immunity,” which is a sour excuse, though not as sour as his pardon by the South Carolina governor, “in exchange for the federal government’s dropping election fraud charges against a group of white South Carolinians.” Perhaps there was simply a dearth of archival evidence, but the true story of this fiasco deserves hearing. As Lineberry suggests, Smalls was equal to the attacks on his character. “My race needs no special defense, for the past history of them in this country proves them to be equal of any people anywhere. All they need is an equal chance in the battle of life.” That he would not be given, but he did display exemplary courage for every shred of humanity he won.

The book is a neat piece of narrative history, told with exceptional brio. It flows with energy and bravado. It's also a crisp reminder that history is never tidy. Thanks, then, to Lineberry for reminding us of the existence of such people as Smalls, and Small, Gourdine, Turner, Jackson, Alston, Chisholm, Morrison, their wives, and their children.