'Code Girls' tells the captivating story of America's female World War II codebreakers

“Women’s work” has an unwritten definition: Long on hours, short on respect. Tedious, backbreaking and underpaid or not paid at all. Maids and factory workers, nurses and store clerks, homemakers and mothers.

Add another category to the list: Code breakers.

Before and during World War II, more than 10,000 American women secretly devoted their lives to breaking and creating the maddeningly complex codes used by the world’s military and diplomatic forces. Nothing less than victory or defeat was at stake, all tied up in the perplexing patterns of numbers and letters.

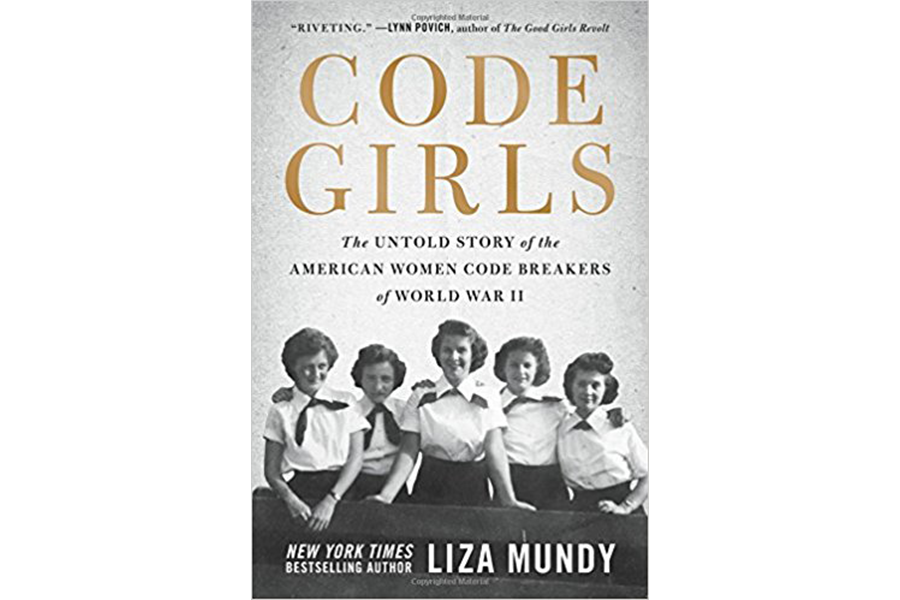

“The military and strategic importance of their work was enormous,” writes journalist and author Liza Mundy in her captivating new book Code Girls: The Untold Story of the American Women Code Breakers of World War II.

But the crucial role of these “high grade” young women, many of them surreptitiously plucked from women’s colleges, was “one of the best-kept secrets of the conflict.” At least, that is, until now.

Mundy learned about the women from a book about a decades-long counterintelligence operation that referred to the surprising number of wartime code breakers who were female schoolteachers. Intrigued, Mundy uncovered a hidden world.

As so often happens in wartime, women picked up jobs that would otherwise have gone to men and accepted lower pay for the same work. Code breaking was another kind of “assembly line,” Mundy writes, one that allowed women to attack the enemy with brains instead of bombs.

Mundy doesn’t entirely succeed in deciphering the extraordinary complexity of codes and cryptography for layperson readers. It can be hard to understand exactly how codes were created and cracked.

But it’s clear that plenty of brainpower was needed along with a unique blend of individual and collective genius. Above all, code breakers needed to detect patterns, often through deep understanding of the inner workings of languages, message formats and mathematics itself.

As Mundy writes, it helped that many women were used to record keeping, filing, and running tabulators and keypunch machines.

The thousands of female code breakers faced other challenges. They couldn’t talk about their jobs and many lived in cramped conditions. Infighting and workplace drama were common. The women worked in “an environment of large and clashing male egos,” Mundy writes, exacerbated by factors like potentially disastrous tensions between the rival Army and Navy code breaking units. To make matters worse, men often dismissed the accomplishments of women, sometimes for competitive reasons, and judged them by their looks.

This isn’t a story of resentment and victimization, however. Despite their frustrations and isolation, these young women sought and found camaraderie, companionship, and romance.

Charming love letters tell part of their stories, but the personal memories of the women themselves are at the heart of “Code Girls.” Mundy interviewed several code breakers, women now in their 90s whose frailty can’t hide their grit.

One refused to cancel an appointment after breaking her wrist and told Mundy to drop by the emergency room for a chat. Another walked several blocks to meet her for a beverage when the D.C. subway broke down. A third gave her balled-up socks “to throw at the television whenever a politician said something inane.”

Another code breaker, one of the stars of the book, fretted about finally telling secrets even though the feds said it was OK and plenty of self-aggrandizing men from back then had already spilled the beans. “Let it rip Mom!” urged her son. So she did.

“It was easy,” Mundy writes, “to understand how women with this much spirit and fortitude helped the allies win the war.”

Speaking of spirit and fortitude, many readers will compare the women of “Code Girls” to those in 2016’s bestselling “Hidden Figures,” which became a surprise hit movie nominated for an Academy Award for Best Picture. Both books rely on personal interviews, oral histories and archives, and neither author stoops to imagining scenes or creating dialogue.

“Hidden Figures” author Margot Lee Shetterly writes that the title of her book is “something of a misnomer.” The history of NASA’s black mathematicians “wasn’t so much hidden as unseen,” waiting for someone to find the pieces and pull them together into a wider story.

Books like “Code Girls” and 2013’s “Girls of Atomic City” share Shetterly’s devotion to sharing the stories of neglected heroines of the 20th century. Here’s hoping these books mark a publishing trend that, like a woman’s work, is never done.

Randy Dotinga regularly reviews books for the Monitor.