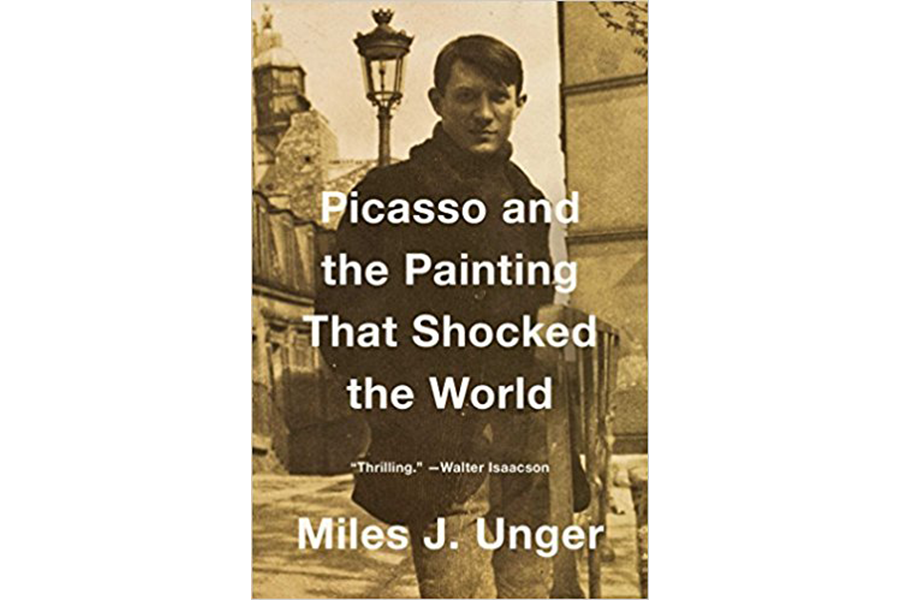

'Picasso and the Painting that Shocked the World' depicts the heady, hardscrabble Paris years

When the Bateau-Lavoir, the run-down tenement where Picasso spent his early years in Paris, was designated a national monument in 1969, the great artist laughed, “Heavens! If anyone had told us when we were there!” Miles Unger brings that heady, hardscrabble period to life in his illuminating new book, Picasso and the Painting that Shocked the World, which culminates in the creation of the radical 1907 masterpiece "Les Demoiselles d’Avignon."

Picasso arrived in Paris in 1900, an 18-year-old with precocious talent and enormous ambition who, at that point, couldn't afford art supplies. In the Bateau-Lavoir, he surrounded himself with a bohemian band of admirers and co-conspirators who recognized his genius, including writers Max Jacob and Guillaume Apollinaire.

He lived for much of his time there with Fernande Olivier, the first in a line of muses the artist would idealize and then discard, and her memoir of those years helps Unger portray them so vividly – the poverty, the creative ferment, the passionate and occasionally tragic friendships and love affairs. When Picasso brought Olivier to Barcelona for a visit, she noted that her stormy and jealous lover was happier and more at ease in his native land than in France. But as Unger observes, Picasso “felt himself destined for greatness, and greatness in his mind demanded suffering, not only for himself but for those around him.”

Picasso’s path to fame and wealth seems predestined now, but the author, who has written books on Michelangelo, Lorenzo de Medici, and Machiavelli, gives due credit to Gertrude Stein and her brothers Leo and Michael, whose visionary support of the young Spaniard and his rival (and later, friend) Henri Matisse occurred “in the face of widespread ridicule and in defiance of conventional wisdom.”

Picasso toiled for months on his commanding, stripped-down 1906 portrait of Gertrude, subjecting her to dozens of sittings until complaining, “I can’t see you any longer when I look.” When viewers said the finished portrait didn’t resemble Stein, the artist shrugged, “Never mind, in the end she will manage to look just like it.”

The portrait of Stein, Unger argues, represented a “seismic shift” in Picasso’s early career that helped launch him into the masterwork that is the book’s focus. Picasso struggled for “eight anguished months” on Les Demoiselles, in a studio paid for by the Steins, filling 16 sketchbooks with hundreds of preparatory drawings. “During these months of intense work,” Unger writes, “a painter of late-nineteenth-century sensibility was reborn as a prophet of modernity, one whose utterances seemed to ring with both the promise and the peril of the new age.”

"Les Demoiselles d’Avignon" depicts five naked women, prostitutes in a brothel. Picasso, recently influenced by Iberian sculpture and African masks, abandoned traditional representations of the human form, creating figures that are jagged, distorted, and disturbing. The two figures on the right, the author observes, were painted “in a form so novel, so aggressively defiant of any canons of beauty or proportion, that more than a century later they still give off a malevolent energy.” (Given the painting’s subject matter, its form, and its creator’s well-documented cruelty to women, one wishes Unger had grappled more rigorously with the question of Picasso’s misogyny.)

The initial response to the painting was unequivocal: it was “greeted with bafflement, suspicion, and outright hostility,” Unger writes, noting that Matisse considered "Les Demoiselles" “not only a crime against art but a personal affront.” Unger skillfully evokes a period when the stakes of art were so high that a painting had the power to destroy relationships. Picasso accepted the consequences. In an elegant metaphor, the author declares that “those who had once shared [Picasso’s] vision and championed his cause were left behind on the platform while he sped off into the future.”

The one peer who did understand what Picasso was grasping toward was Georges Braque. For the next several years, they embarked on a unique artistic partnership – Braque likened them to “two mountain climbers roped together” – developing the school of painting known as Cubism.

“There was simply no way to predict a Picasso or Braque Cubist still life of 1909 from the work that preceded it; this was not evolution but revolution, as profound and disturbing a dislocation as has ever occurred in the history of art,” Unger asserts. The revolution carried Picasso far from the Bateau-Lavoir, but looking back years later, he remarked wistfully to an old friend, the poet Andre Salmon, “We were never truly happy except there.”