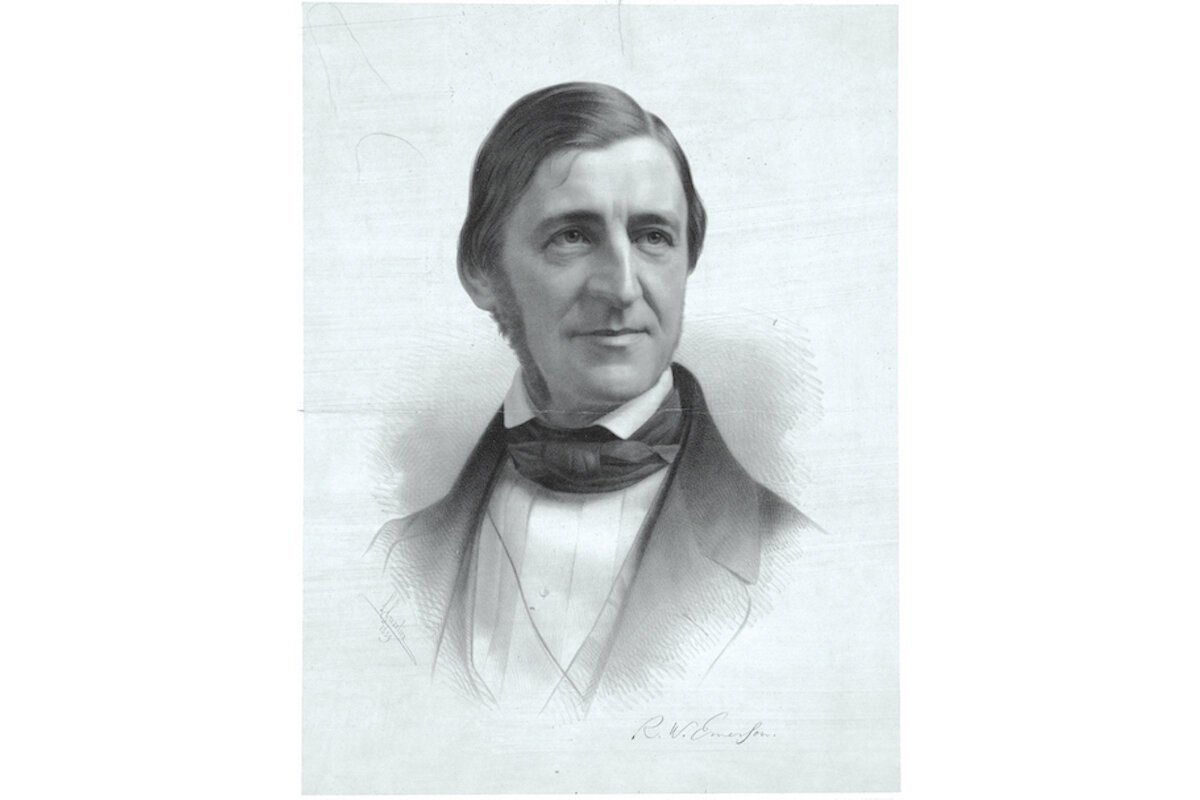

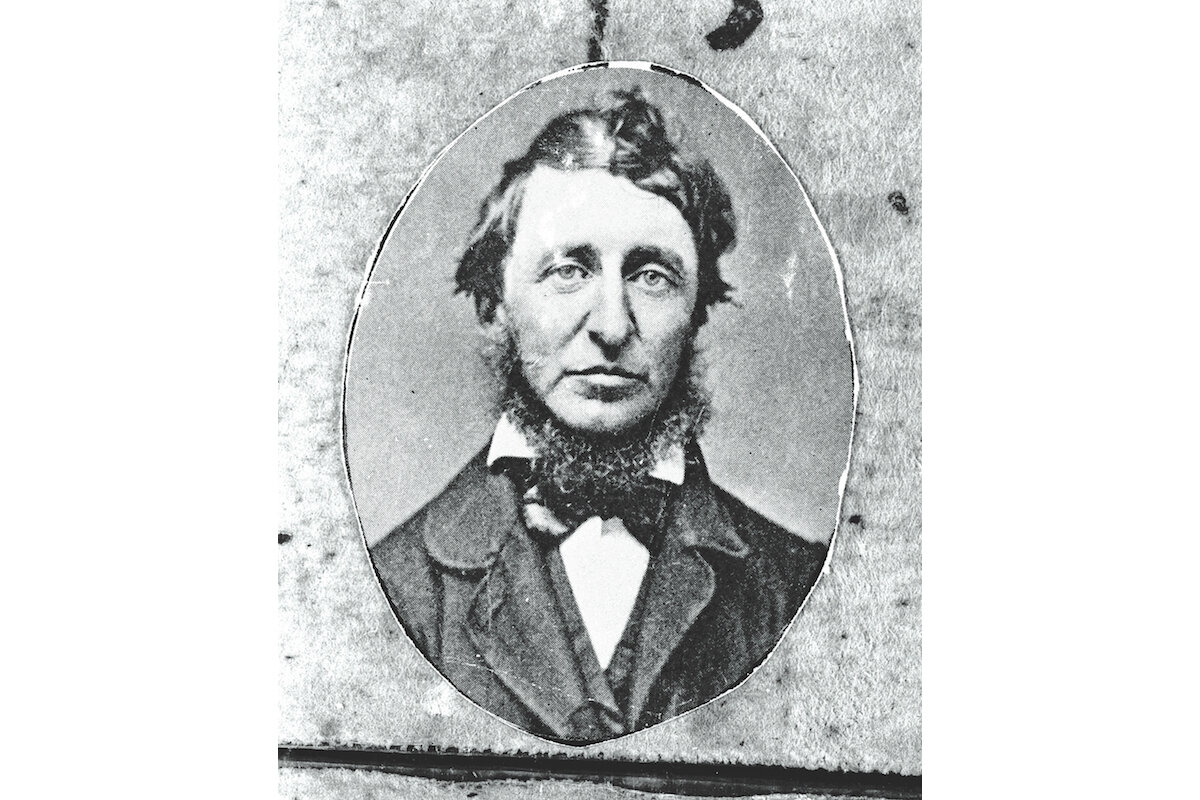

'Solid Seasons' delves into Emerson and Thoreau's friendship

Seemingly everyone in Concord, Massachusetts, noticed that Henry David Thoreau (1817-1862) was an imitator of the already famous author Ralph Waldo Emerson (1803-1882). Emerson knew from the start of their friendship in 1837, however, that Thoreau was creating something different with the intellectual material that Emerson had mined. Emerson did not begrudge it: “I am very familiar with all his thoughts, – they are my own quite originally drest.”

In Solid Seasons: The Friendship of Henry David Thoreau and Ralph Waldo Emerson, author Jeffrey S. Cramer describes how, as in all long friendships, the pair had their sunny and overcast days as well as periods of revelation and frustration. He writes: “While Emerson found Thoreau’s constant aspect of reform and rebellion tedious – ‘Always some weary captious paradox to fight you with ...’ – Thoreau saw a man he doubted ‘could trundle a wheelbarrow through the streets, because it would be out of character.’” Each helped the other see himself – both strengths and limitations – more clearly. “If I have not succeeded in my friendships,” wrote Thoreau in his journal, “it was because I demanded more of them and did not put up with what I could get; and I got no more partly because I gave so little.”

To my surprise, being a Thoreau man myself, Emerson comes off better and wiser and he’s more perceptive about and accepting of his friend: “It seemed as if his first instinct on hearing a proposition was to controvert it, so impatient was he of the limitations of our daily thought. This habit, of course, is a little chilling to the social affections; and though the companion would in the end acquit him of any malice or untruth, yet it mars conversation. Hence, no equal companion stood in affectionate relations with one so pure and guileless.”

Thoreau had an extraordinarily fine and responsive vision of the natural world, but he viewed adults as almost all of a kind. He hated recognizing Emerson’s conventionality and ability to be not only a social family man but a grand “representative” man. Thoreau took Emerson’s help, interest, and favors for granted and gave in return only himself; but even that exchange of benefits disappointed Thoreau, as he felt in Emerson’s presence that he could not be absolutely open: “It is impossible to say all that we think, even to our truest Friend.” This was a sad reflection, but elsewhere Thoreau declared rather more plaintively: “Actually I have no friend. I am very distant from all actual persons.” Friendship with Emerson could not build a bridge from Thoreau to a landscape where he was satisfied with humankind.

Both suffered losses of beloved family members, but Emerson more so, in greater number and in closer proximity. Neither could lighten the other’s grief, but Emerson was more observant of his friend’s qualities than Thoreau was of his. It surprises me how vague Thoreau is when it comes to detailing his thoughts about Emerson. While Thoreau’s journals can excite one’s interest in the seasonal changes and very particular characteristics of creatures and plants, darned if he can ever pinpoint Emerson’s or anybody else’s personality.

Thoreau’s literary influence has grown into international renown while Emerson’s writing seems stuck in its own time and place. Thanks to author Jeffrey Cramer, we can see that for all of Thoreau’s integrity, he could not fully appreciate Emerson. Thoreau lacked Emerson’s ability to love another, warts and all.

Bob Blaisdell edited “Thoreau’s Book of Quotations” for Dover Books.