‘Lieutenant Dangerous’ uses wry humor to point out the absurdity of Vietnam War

Like many young men growing up in the late 1960s, Jeff Danziger thought about what the war in Vietnam would mean for him. Decades later, and after a distinguished career as an editorial cartoonist for The Christian Science Monitor, he recounts the story of his military experiences in “Lieutenant Dangerous: A Vietnam War Memoir,” a book that is by turns funny, sad, horrifying, and thought-provoking.

Danziger initially avoids the military draft as a college student. But once he graduates, his deferment ends and military service becomes inescapable. As he rides the bus to Fort Dix for basic training, he finds himself weeping. “I realized,” he writes, “that I was going ... to fight in a questionable war in a country that I knew nothing about and cared nothing about, to be trained to shoot and kill people against whom I had absolutely no complaint.” He is, in short, a reluctant soldier.

He searches for a way to keep out of the actual fighting. He decides that “intelligence” sounds promising because it requires “listening to the radio all day and making reports about enemy movements and secret stuff.” This requires language training, which will extend his enlistment but will also keep him out of the war zone for a year. When the language training concludes, he decides to become an officer and thus postpone overseas duty even longer.

But the Army, in its wisdom, makes him an ordnance officer, a job that involves replacing artillery tubes on fire bases – exceptionally dangerous work often conducted under fire.

The book reads like a cross between Joseph Heller’s “Catch-22” and the television show “M.A.S.H.” Parts of the story reflect his own innocence, such as his decision to write a letter to his senator protesting his assignment as an ordnance officer when he was a trained language specialist. But it works. He gets transferred and uses his language skills, but he is still in the middle of the fighting, often on missions that are poorly thought out and, sometimes, appear suicidal. In one case, all the South Vietnamese military officers working with him desert rather than enter the combat zone.

All the horror and stupidity associated with the Vietnam War are on full display: the inflated body counts, the waste of resources, the lack of strategic thinking, the indifference to civilian casualties, the effort to transfer responsibility to the South Vietnamese and their reluctance to accept it, officers more concerned about their careers than about their men, and the days and weeks of wasted time and effort.

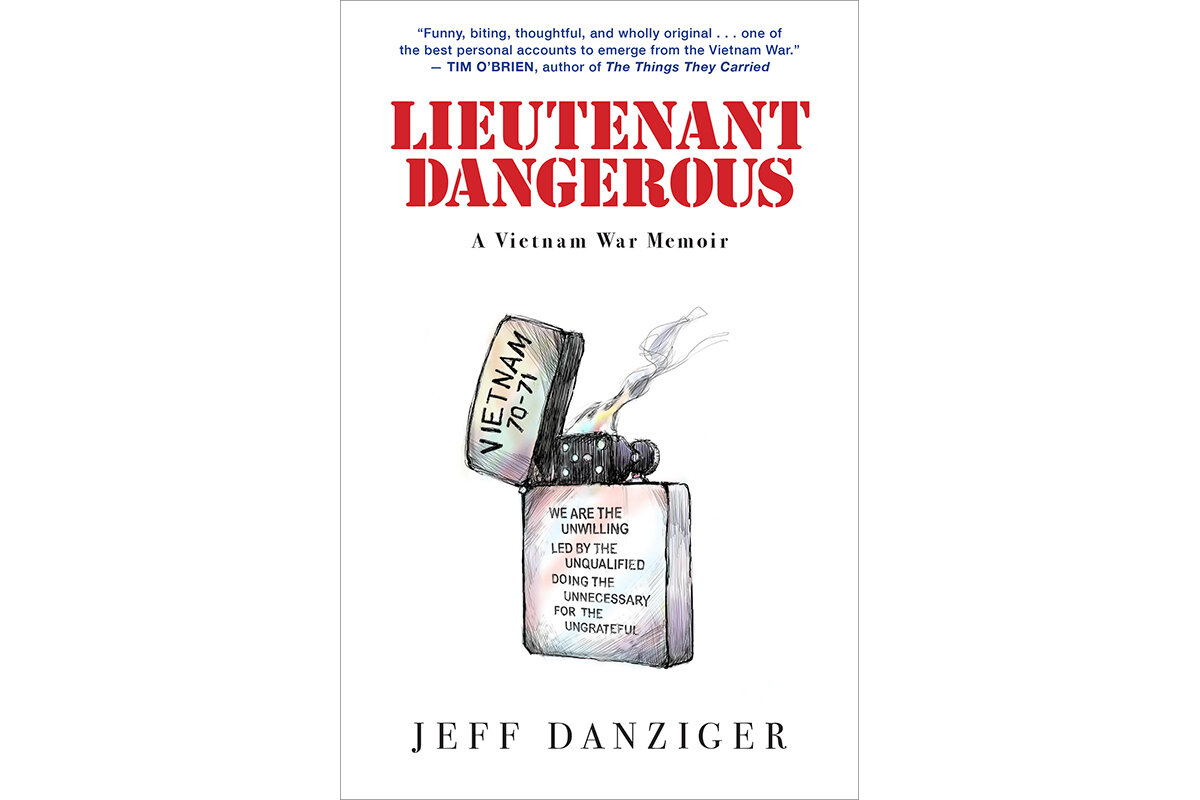

His memoir includes a number of line drawings that help illustrate the story. We see a hostile-looking draft board poised to decide a young man’s future, a couple looking pensive as the man is about to depart for military service, a B-52 dropping a stack of bombs, the M113 armored personnel carrier, and an eerily smiling Richard Nixon on a television set. Danziger even sketches a helicopter equipped with giant speakers – used (not too successfully) in an effort to scare the enemy into surrendering. These lack the drama and punch of a full-size editorial cartoon, but they give us further insights into the emotions and experiences that he details in the text.

The author makes a convincing case that he was an indifferent and ineffective soldier. But one suspects that there is more to the story. While in Vietnam he received a Bronze Star, given for heroic achievement or service in a war zone, and an Air Medal, denoting heroic or meritorious achievement in flight. But he is neither happy nor satisfied when his tour of duty ends. On the flight home, he discovers that the prevailing mood among the returning soldiers is not happiness, but “relief at having survived where others didn’t” and apprehension about “what return would mean.”

Like many other veterans, Danziger left the military and moved on with his life. He wrote this book after conversations with young people made him realize that those who didn’t grow up during the war needed context to understand it.

He concludes by asking the reader to ponder: Would you leave the life you were living “because you trusted people in power?” or, “Would you be like me? Planning a secret internal defense against all the doubt and discomfort of protest and wanting simply not to stand out.”

It’s a good question, but not entirely fair. It’s unreasonable to ask readers to make a decision when they know how the story ends. The American loss and all that has happened since then inevitably change one’s perspective. And besides, in post-World War II America, most young people were predisposed to do what was expected. Or as Danziger notes, “We had no choice.” Like most of his fellow soldiers, he was hard-wired to follow orders.

“Lieutenant Dangerous” is also a cautionary tale. Wars are never simple and rarely turn out as expected. Military campaigns look straightforward to those who plan them. But the reality is so often different.