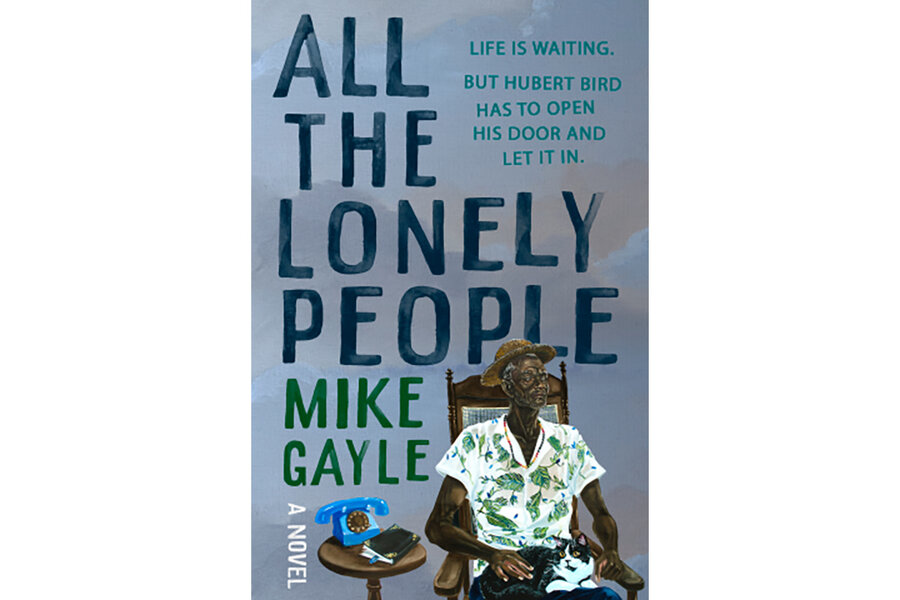

Warmhearted ‘All the Lonely People’ strikes at isolation

“All the Lonely People,” a winning new novel by English author Mike Gayle, launches with a frothy sitcom premise, but quickly sails into rougher waters – first and foremost, the crisis of loneliness.

It’s a timely topic. Britain appointed its first minister of loneliness in 2018, citing sobering statistics and a host of physical and mental ills related to social isolation. The pandemic lockdowns of 2020 exacerbated the issue. With his novel, Gayle sets out to show how one individual slides from lively to lonely – and then shares possible avenues of escape.

Hubert, a dapper Jamaican immigrant in his 80s, lives quietly with his cat in the borough of Bromley. One day the doorbell rouses him from his favorite armchair. On the step stands a young blond woman and her toddler from next door. New to the neighborhood, the duo – mom Ashleigh and daughter Layla – have come to introduce themselves. Hubert, startled into near silence by Ashleigh’s buoyant chattiness, doesn’t engage.

Days later, Ashleigh and Layla are back. This time they need help. Ashleigh’s got a job interview, the babysitter canceled, and could Hubert please look after Layla for “twenty minutes ... half an hour tops”? Appalled at the request but even more uncomfortable with Ashleigh’s desperate tears, Hubert passes her a clean handkerchief and agrees. “Me will help you out, okay?” he says. “Just tell me what it is you want me to do and me do it.”

Readers may quickly spot a solution: Here are the friends Hubert seeks! But the man himself, formal by nature, shrouded by sorrows, and convinced friends come in only one size and shape, can’t make the connection – at least right away.

To explain how Hubert’s “once-full life had emptied,” Gayle brings readers back to June 1957 in Jamaica. In his early 20s, Hubert listens as best friend Gus – likable, social, impulsive – convinces him to make the leap to a new life in England. The book’s second plotline kicks off there, alternating with chapters in the present.

Gayle leans on history in creating both characters. Hubert and Gus belong to the Windrush generation, which consisted of thousands of Caribbean people who were encouraged to migrate to Britain between 1948 and 1971 to alleviate the nation’s postwar labor shortage. Gayle’s own parents made the trip from Jamaica to Britain in the 1960s. In a recent interview with The Guardian, he shared that he was unaware of the noxious racism they and their fellow immigrants faced until he started researching the novel.

In the book, the young Hubert quickly finds a job in a department store warehouse. “The lads are not going to like this,” mutters the white foreman upon meeting Hubert. “The lads” turn out to be Hubert’s co-workers, racists all, who subject the Black newcomer to slurs, suspicion, and, ultimately, attacks.

Yet Hubert prevails, facing off with the prejudiced pack and creating a space in which he can survive, if not thrive. It’s a life-defining choice. Soon, he meets a white woman named Joyce who works in the haberdashery department. They fall in love and, in spite of her family’s apoplectic objections, decide to get married.

Years of joy and struggle follow, as their growing family – beginning with daughter Rose and, later, son David – faces discrimination and hate. Gayle shares their indignation, sadness, and anger in straightforward, unadorned prose. The simplicity is effective.

As the present-day storyline progresses, Hubert’s social reluctance thaws. He musters the courage to drop by the local club for people over 60. He visits often with Ashleigh and Layla. He offers a cold drink to a sweating Latvian deliveryman, who reminds Hubert of his own early struggles as an immigrant. The gesture leads to a warm friendship.

A late-story plot twist adds both tragedy and momentum to the tale, morphing it into a page-turner. The cinematic conclusion feels completely earned, leaving characters jubilant and forever changed.

Gayle wrote “All the Lonely People” before the pandemic, but its theme of emerging from isolation via unfamiliar – and emotionally rugged – paths only to find oneself stronger makes it a GPS for our times.

“You’re a good man, Hubert Bird, I can just tell,” says Ashleigh early on; it’s a sentiment echoed by many people. As it dawns on Hubert that companionship takes infinite forms and can spring from unlikely sources, he allows himself to enjoy, once again, what happens when you open the door with courage and kindness.