‘The Chancellor’ expands on the exceptional life of Angela Merkel

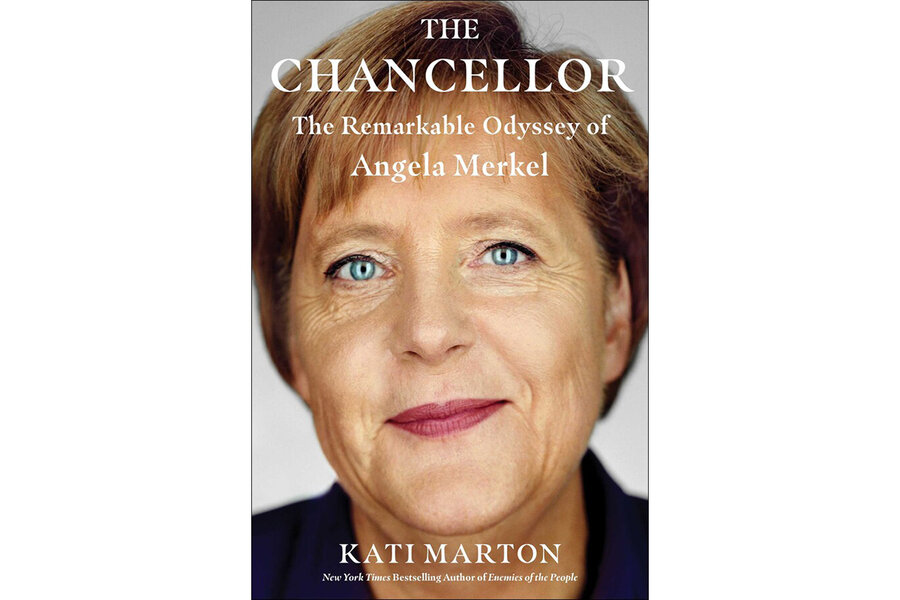

As German Chancellor Angela Merkel steps down after 16 years at the helm of global leadership, her full legacy will inevitably be parsed by admirers and critics alike. Kati Marton, a renowned journalist and author, has crafted “The Chancellor: The Remarkable Odyssey of Angela Merkel,” an immensely readable and substantial contribution to the current Merkel anthology. This biography contextualizes both the public and private persona and makes clear that Merkel’s reign as chancellor goes well beyond the German borders.

“The Chancellor” begins with an exploration of Merkel’s early political education as a child in a small town in the Soviet-occupied East Germany. Her demanding father, a Lutheran pastor, instilled in her a sense of sacrifice, service, and faith. She also learned at an early age the art of survival under an authoritarian regime, most importantly, not drawing notice. “Standing out was dangerous, so she learned not to call attention to herself,” observes Marton.

But it was difficult for the precocious Merkel to not garner recognition. Marton documents how her contemporaries remember Merkel for her intellect and natural leadership abilities. “Today we would call her ‘highly gifted,’” declared her former Russian teacher. This quality, however, did not always put her in the good graces of communist officials. After she won the Russian Language Olympics, local party officers chastised her instructor for promoting a child of the so-called bourgeoisie. “I always had to be better than the others in class,” a reflective Merkel recalled of this period.

As a young adult, Merkel sought solace from the oppressive regime. She pursued studies in physics “because even East Germany wasn’t capable of suspending basic arithmetic and the rules of nature.” She found quiet hope in resistance movements throughout the Soviet bloc that called for greater freedoms. When the Berlin wall came down in 1989, Merkel, who had been living in East Berlin, joined in with her fellow exuberant Ossis (East Germans) to venture into the West.

In her mid-30s, Merkel reinvented herself in a united and democratic Germany. She abandoned her unfulfilling life in science for a career in politics. Under Chancellor Helmut Kohl’s leadership, she went from press officer to minister in a matter of years. She was often selected as the token woman and Ossi in the male-dominated Christian Democratic party. Regardless, Merkel took the opportunities before her and kept her politics simple. She stuck to the familiar tunes of hard work, which included developing an unassailable command of facts, and maintaining a low profile.

Despite Merkel’s unassuming presence, her competitive nature also showed itself in knowing when to go on the offensive to further her own prospects. Marton describes an intrepid Merkel on a crusade when Merkel decided to root out her mentor, Chancellor Kohl, as he was besieged in a donation scandal. Next, she would calmly supplant Social Democratic Chancellor Gerhard Schröder in 2005 and assume her historic position. “This is her power move: letting an alpha male keep talking and waiting patiently as he self-destructs,” notes Marton.

Merkel’s approach to governance was classically conservative. She consistently opted for incremental and consensus-based change. As an Ossi who bore the scars of the direct aftermath of World War II, she proved to be the strongest advocate for upholding the liberal international order. “The Chancellor” offers a compelling take on Merkel’s role as a crisis manager who fought to protect institutions such as the European Union and NATO from enemies both foreign and domestic. From confronting authoritarians and populists to reassuring the public during the coronavirus pandemic, she was an imperfect master at balancing political interests with high-minded principles.

The most consequential decision that Merkel made as crisis manager was, of course, providing asylum for approximately one million refugees in 2015. Marton does a stellar job of laying out the moral, political, and social implications of this choice. “Given Merkel’s Lutheran values, her grounding in Germany’s darkest history… it is possible that the chancellor truly felt she had no alternative,” Marton speculates. During this humanitarian crisis, Merkel spoke from a deep moral conviction when she declared, “If Europe fails on the question of refugees, then it won’t be the Europe we wished for.” Germany, which sought to right its own dark legacy, would be the country to set an example.

Merkel would soon learn that not all of her fellow Germans were as welcoming. A backlash was fomenting that culminated in the rise of the far-right Alternative for Germany party. It was in the former East Germany that the fallout was most pronounced, as “leading populists in Merkel’s region [began] to fear that aid to Syrians would mean less for them.” Merkel continued to make the case for her policy, but her appeals were ignored. She never wavered from her decision but slowly began to realize that she had failed “to connect with people whose grievances – imagined and real – made them ripe for populist exploitation.”

The private Merkel also makes an appearance in this biography, with accounts of her marriages, her love of music and nature, and her sense of humor on full display. After finishing the book, readers will likely feel that the description of Merkel as “elusive” no longer serves. It becomes apparent that Merkel’s intentions are usually hidden in plain sight. Often, it takes a writer of Marton’s caliber to reveal what has been in front of us the whole time.