Who invented motion pictures? Hint: Not Edison nor the Lumières.

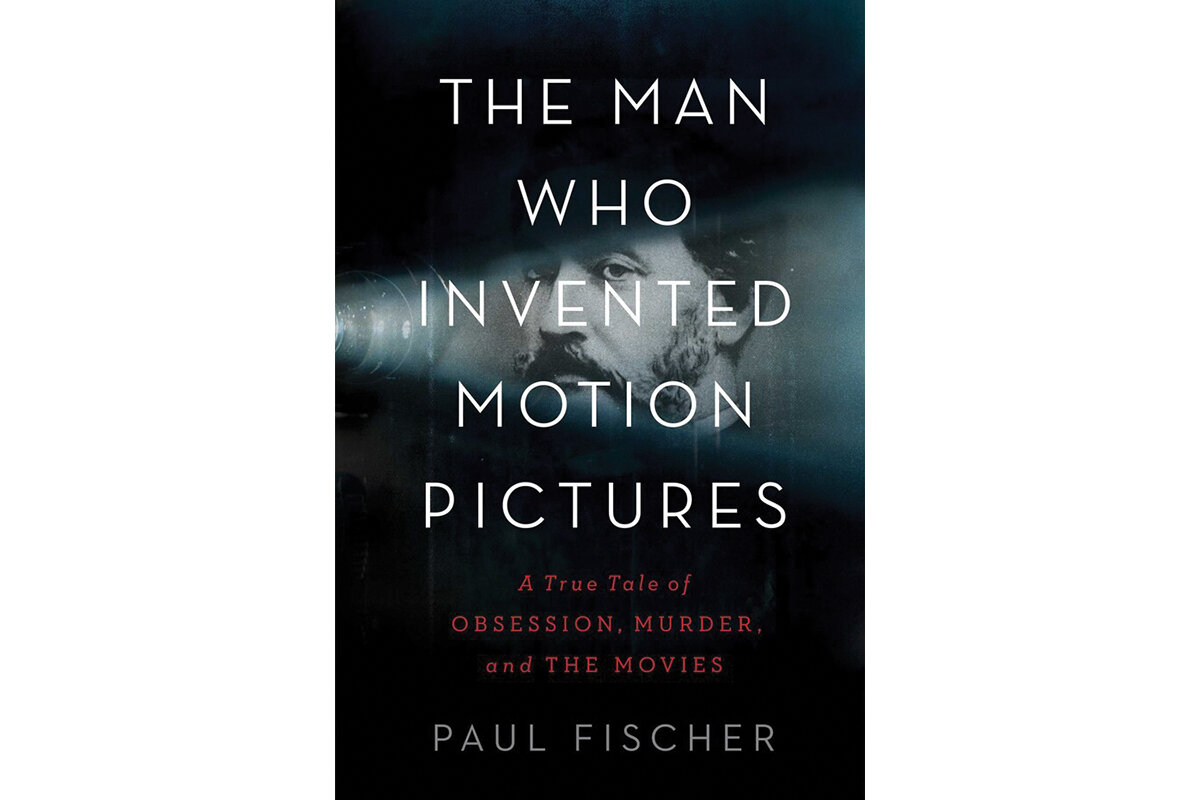

Sometimes history gets it wrong. In “The Man Who Invented Motion Pictures: A True Tale of Obsession, Murder, and the Movies,” filmmaker and author Paul Fischer makes a compelling case that the real inventor was Louis Le Prince.

On Oct. 14, 1888, Le Prince assembled three family members and a friend as actors at his house in Leeds, England, and, using a hand-cranked camera, photographed them as they moved in a garden.

Why We Wrote This

Digging into history often reveals hidden agendas and motives, and can create a truer record. An author’s research into a forgotten inventor sheds light on the slippery world of late 19th-century inventors.

But more than the history of the motion picture, Fischer’s book explores a mystery and a possible murder.

Le Prince was a polymath who, unlike Thomas Edison, had no reputation, no employees, and no outside funding. But Le Prince was a very practical man, and he filed and received a British patent.

But just before he was to reveal his invention to the world, he disappeared and was never seen again.

Most Americans believe that Thomas Edison invented the motion picture with his Kinetoscope machine in 1891. The French give credit for this development to Auguste and Louis Lumière, who hosted the first commercial motion picture screening in Paris in December 1895.

Sometimes history gets it wrong. In “The Man Who Invented Motion Pictures: A True Tale of Obsession, Murder, and the Movies,” filmmaker and author Paul Fischer makes a compelling case that the real inventor was Louis Le Prince. On Oct. 14, 1888, after four years of work, Le Prince assembled three family members and a friend as actors at his house in Leeds, England, and, using a hand-cranked camera, photographed them as they moved in a garden. The result, Fischer declares, was “the first motion picture ever shot in human history.”

But more than the history of the motion picture, it is a mystery about a possible murder.

Why We Wrote This

Digging into history often reveals hidden agendas and motives, and can create a truer record. An author’s research into a forgotten inventor sheds light on the slippery world of late 19th-century inventors.

Le Prince was a polymath who was born in France, worked in England, and became a naturalized American. He had worked as a teacher, painter, industrial draftsman, and potter. He was an amateur – unlike Edison, he had no reputation, no employees, and no outside funding. But he was a very practical man, and he immediately filed and received a British patent for his invention.

Aided by better-quality film produced by the American George Eastman, Le Prince made plans to reveal his discovery in New York and sent his wife and son ahead to secure an appropriate venue. Meanwhile, he headed to France to take care of some business with his brother, Albert. After meeting his brother in Dijon, he boarded a train to Paris for the return trip. But he never arrived in Paris. Given the absence of a concrete itinerary and the available communications of the time, it took several weeks before Le Prince’s family realized he was missing. An extensive search was mounted, but no trace of the inventor was ever found. Le Prince’s wife, Elizabeth, bereft and living with their children in New York, could only look on from a great distance and wonder what had happened.

When Edison’s machine was revealed several years later, it bore a striking resemblance to Le Prince’s invention and was different from Edison’s previous efforts. The mourning by Le Prince’s wife was soon surpassed by her anger at Edison, who she believed had stolen her husband’s ideas and probably murdered him. Even worse, because her husband was missing and not declared dead, she could not sue to protect her husband’s patents for seven years.

Edison, despite his “aw-shucks” common-man demeanor, was a ruthless businessman with very sharp elbows. He frequently resorted to elaborate lawsuits to bankrupt his opponents. But would Edison go so far as to murder a competitor?

Readers of Graham Moore’s novel “The Last Days of Night,” which fictionalized the late 19th-century fight between Edison and George Westinghouse to spread electricity around the United States, will find echoes of that book – and more evidence of Edison’s hard-nosed

approach to business – in this real-life story of technology, skulduggery, and courtroom battles.

The invention of motion pictures was less of a “eureka” moment than a product of small, incremental improvements. The people involved were unusual and often unsavory characters. Fischer’s adept character sketches bring to life dozens of people who played a role in the creation of motion pictures and help reveal the cutthroat world inhabited by late 19th-century inventors.

What knits the book together is the mystery that has lasted for more than a century. Why and how did Le Prince disappear? Like any good mystery, it features unreliable witnesses, suspicious motives, and scant evidence.

Nothing supports Mrs. Le Prince’s belief that Edison was responsible for her husband’s death. A generation ago, a group of documentary filmmakers working on a television program about Le Prince concluded that he had been pulled from the Seine in Paris shortly after going missing and was buried in an unmarked grave. But Fischer convincingly bats away that hypothesis.

The author thinks that the most likely suspect was the inventor’s brother, Albert. He owed Louis a great deal of money and was the only person to see him board the train to Paris. And, contrary to his assertions that he was leading the search, Albert apparently never reported his brother missing.

It seems a convincing hypothesis, but as Fischer notes, “The identity of his killer, like the role he might have gone on to have in shaping cinema history, will never be known with certainty.”