Survival tale ‘The Wall’ pits a woman against strange forces

Wilderness survival stories offer narratives of process. How do the protagonists make it off the boat, plane, or spaceship alive? How do they find shelter? Food? Companionship? How do they get home – or create it anew? The answers hinge on ingenuity, daring, and resourcefulness.

Some of the best of these books – "Island of the Blue Dolphins,” “My Side of the Mountain” – get shelved in the children’s section, a disservice to adult readers who may have missed them. This summer’s crop of novels includes a survival story for grown-ups that’s as pulse-thumping as it is thought-provoking.

And it’s 60 years old.

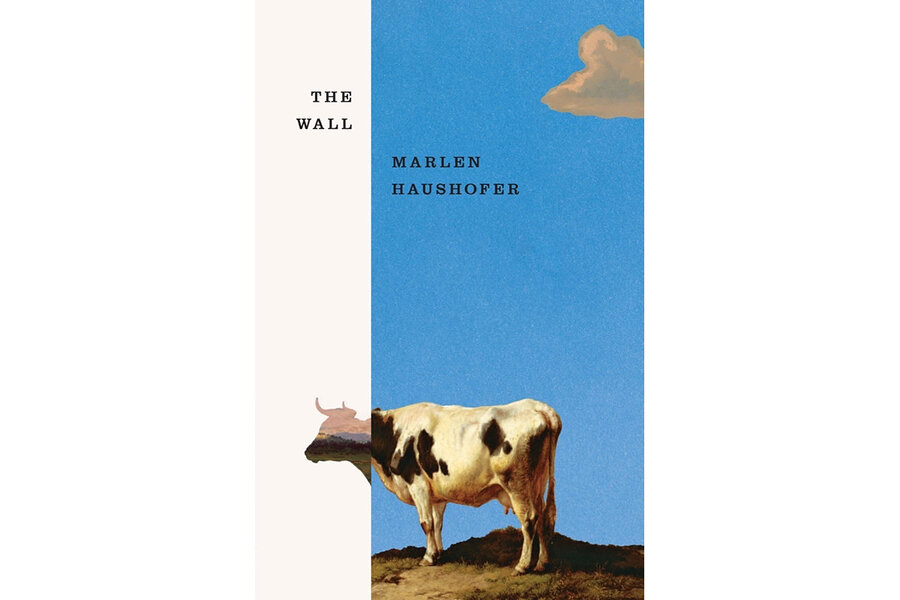

“The Wall,” written in 1962 by Austrian author Marlen Haushofer, is her only work translated into English. The novel has earned high praise over the decades, and continues to feel remarkably well-tuned to the concerns of the day.

The story opens with the narrator, a middle-aged widow whose name we never learn, announcing the purpose of the forthcoming account. “I’m quite alone, and I must try to survive the long, dark winter months,” she writes matter-of-factly. “I’ve taken on this task to keep me from staring into the gloom.”

In a mere handful of pages, the reason behind her solitude and apprehension becomes clear. Seven months earlier, the woman had joined her cousin and his wife for a three-day vacation at their hunting lodge in the forest. After arriving, the couple departed for the closest village with their Bavarian bloodhound, Lynx, while the woman stayed at the lodge. The dog returned by nightfall, but the couple never reappeared.

When woman and dog head out to investigate, they run – literally – into the cause. “A smooth, cool resistance where there could be nothing but air” blocks their path to the village. Dubbing it “the wall,” she determines this invisible, impenetrable presence is not only preventing her from leaving the forest, but it’s protecting her from a disaster on the other side. The few humans she can see are frozen in place, as if turned to stone.

“We were in a bad situation, Lynx and I,” the woman assesses. “But we weren’t lost entirely, because there were two of us.”

Thus begins the hard work of survival in a wild, rugged patch of Austrian forest by a woman utterly unprepared for such a trial. What she does possess is good sense; she’s keenly aware of the need to procure food, catalog the lodge’s contents, and map her surroundings, all tasks she approaches with diligence.

The woman’s other life-saving advantage is an expanding roster of companions. Two days into their plight, she and Lynx discover a cow – bewildered and in need of milking, but otherwise healthy – near the wall. The woman milks her on the spot, guides her back to the lodge and creates a stall in a nearby hut. Naming the gentle beast Bella, the woman admits, “this cow, while certainly a blessing, was also a great burden…. She was dependent on me.”

Less dependent is a cat who appears on the porch one night, suspicious and hesitant. Soon, she, too, finds her place in the household, becoming “a brave, hard-nosed animal that I respected and admired, but one who always insisted on her freedom.” The woman’s knotty relationship with the cat – and, later, her progeny – provides one of the book’s rich pleasures.

Haushofer chronicles the day-to-day hardships and feats of this unconventional quartet in one fell swoop: From first page until last nothing slows the narrative flow, neither chapter breaks nor white space. It’s a stylistic choice that befits the inescapable and unending demands of survival in a northern forest. Readers must decide when to take a break and a breath, although it’s tempting to power through, agog.

The twin titans of weather and hunger batter the narrator of "The Wall." An unseasonable cold front in May underscores the importance of augmenting the woodpile before winter, as well as stockpiling hay and planting potatoes and beans. “How terrible it is to be dependent on an unsatisfied body,” writes the woman. Yet when the first new potatoes sprout, she finds she’s forgotten the taste of favorite foods from her past. Yearning has been replaced with a fresh satisfaction.

And that’s just the start of the woman’s steady transformation. As she tackles the tasks before her – from hauling hay, chopping wood, and finding fruit, to helping Bella deliver a calf – strength replaces inability, and tireless drive overcomes inertia. Haushofer takes her time describing these day-to-day efforts and the attendant, hard-fought progress. It’s engrossing reading. Page after page, it’s hard not to wonder, “What would I do in her shoes?”

Smoothly translated by Shaun Whiteside, the novel’s unadorned prose and minimal references to its particular era give it a timeless, meditative weight. The most vivid descriptions seem reserved for the power, threat, and beauty of the ever-present landscape. At the start of their first summer, the woman and her animals hike up the mountain to a smaller lodge on the edge of a meadow. “It was always in gentle motion,” she observes of the grassy expanse, “even if I thought the wind was still.”

The narrator doesn’t shy from describing bouts of hopelessness, exhaustion, and despair; loneliness, too, haunts her. These are familiar struggles for many in these pandemic-tinged times, which may make these sections hard to take. Time and again, though, the woman emerges from the darkness thanks to the life in her midst. “I couldn’t flee and let my animals down,” she tells the reader.

What sets “The Wall” apart from other survival tales is the removal of the world beyond. While Haushofer never explains exactly what the barrier is, who made it, and why, the woman muses occasionally about its origins and implications. With no one around to convince but herself, the “why” becomes pointless. Besides, food must be cultivated and animals tended to.

A late-story spasm of violence brings heartbreak, but once again the woman persists. “Something new is coming and I can’t escape that,” she declares. “I shall deal with it and find a way.”

Six decades later, “The Wall” continues to deliver a remarkable tale of determination that lingers long after its final page.