‘Wilderness Tales’ unfolds short stories with a sense of place

No doubt anyone who enjoys camping out under the stars, hiking along trails through sylvan landscapes, or spending meditative time in places with more bears than people will likely have presentiments about a collection billed as “wilderness tales.”

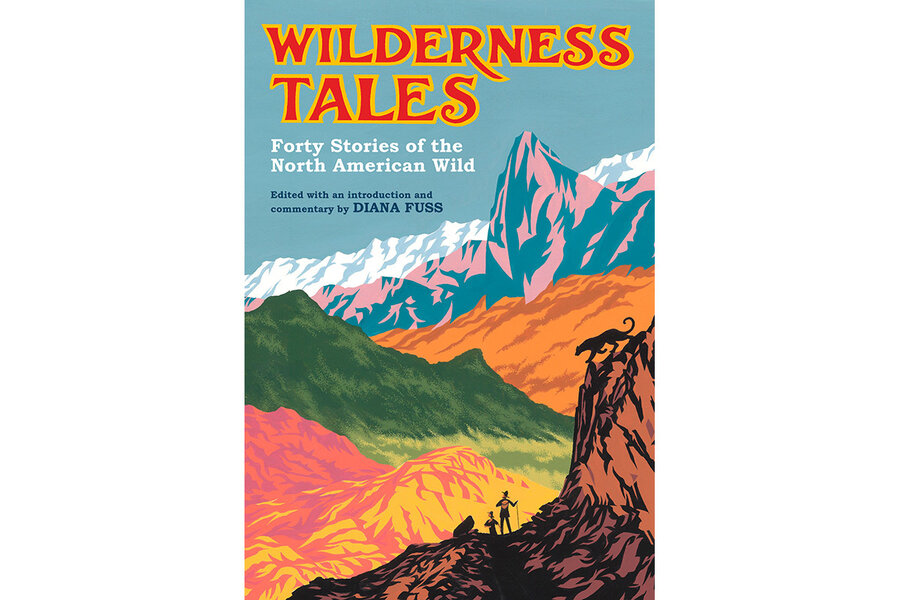

Editor Diana Fuss moves beyond typical nature stories in the anthology “Wilderness Tales: Forty Stories of the North American Wild.” She’s after bigger game: the short story genre itself. As she writes in the introduction, “In the first half of the nineteenth century, the explosion of cheap, consumable, and transportable magazines and journals proved to be the perfect vehicles for generating and sustaining a literary form also new to the scene, the literary sketch or tale, soon known as the short story.”

To demonstrate the evolution of the American short story, Fuss has collected 40 stories by famous and not-so-famous writers, beginning with Washington Irving’s “Rip Van Winkle” (1819) and ending 100 years later with Tommy Orange’s “New Jesus” (2019). This progression from Wilderness Gothic to the present-day dystopian climate fiction offers a highly eclectic rendering of the continent’s natural history.

Fuss’ choices can sometimes seem puzzling. The collection consists of many great stories, but the wilderness link in some of them is tenuous. Perhaps it has something to do with her definitions: “‘Wild’ denotes unsettled terrains and their wildlife, while ‘wilderness’ encompasses the changing stories we tell about them,” she writes.

Laying aside preconceptions, however, and diving into the stories themselves – and there are just enough really fantastic ones to keep you reading – offers insights and rewards. These include classic tales such as “To Build a Fire” by Jack London and “The Wolfer” by Wallace Stegner – both certainly standard bearers of the wilderness-tale genre. And Ernest Hemingway’s “Big Two-Hearted River” never fails to bathe the reader in an ambience of quietude, contentment, and meditation.

There are a few stories that surpass any expectations one may have regarding wilderness tales or short stories of any genre. “Trail’s End” by Sigurd Olson is the story of a wounded buck told from the deer’s point of view. Readers travel to the Big Woods of northern Minnesota during hunting season, following the intrepid animal as he outruns, outsmarts, and outswims his human and canine pursuers. It’s a white-knuckler from start to finish.

Marjorie Pickthall’s “The Third Generation” is a masterpiece of a tale that follows two men who, in their small canoe, set out across the western Canadian wilderness, through ”the endless chain of unknown and uncharted lakes” with an old map in search of a mythical river. This short story, like a miniature “Heart of Darkness,” poses poignant questions about North America’s past. As Fuss puts it, “Unique for its time, this story goes well beyond the typical expedition adventure narrative, instead raising meaningful and far-reaching questions of historical guilt and generational atonement by asking whether the sins of the fathers might yet be visited on their descendants.”

Other stories are drawn from the cli-fi, bio-punk genre and are great fun to read. T. C. Boyle’s “After the Plague” is a three-ring circus of entertainment, depicting the misadventures of a schoolteacher on “sabbatical” up in the High Sierras during a world-wide pandemic that kills off most of our species except for a few “winners.” I won’t ruin the ending. “The Tamarisk Hunter’’ by Paolo Bacigalupi is a walloping broadside against the dysfunctional management of water resources, particularly in California.

In the end, this collection of stories about the North American wilderness does offer serious cause for reflection about the state of our wilderness. As Fuss herself writes: “When will the domain of the wild be beyond all possible recovery, and who will we be without it?”