Anna May Wong blazed a trail for Asian actors in Hollywood

Loading...

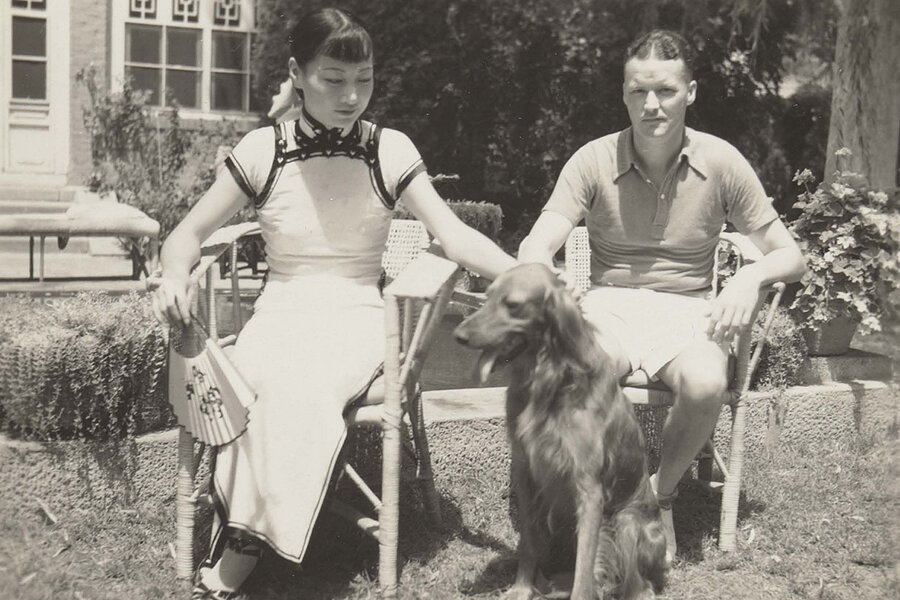

Before Asian actors Lucy Liu, Michelle Yeoh, and Awkwafina graced screens big and small, there was Anna May Wong.

Working in and out of Hollywood from the mid-1910s until the early 1960s, the groundbreaking Chinese American actor cut a distinct path in entertainment history. She appeared in more than 60 movies – as well as plays, TV series, and vaudeville shows – at a time of limited roles, shoddy contract terms, and rampant stereotypes for Asians working in Hollywood.

In “Daughter of the Dragon: Anna May Wong’s Rendezvous With American History,” writer and scholar Yunte Huang offers the final volume in his trilogy that explores, as he puts it, “the Asian American experience in the making of America.” Aiming his curiosity and penchant for research at Charlie Chan, conjoined twins Chang and Eng Bunker, and now Wong, Huang delves into individuals who soared into the pop culture consciousness of their day despite political tumult, racial bias, and xenophobia. Wong’s story feels particularly relevant today.

Born in Los Angeles at the dawn of 1905, Wong Liu Tsong started life on South Flower Street near Chinatown (she would adopt the Anglicized moniker Anna May as a teen). Her father, Sam Sing, owned and operated Wong Laundry, behind which the family – mother Gon Toy, older sister Lew Ying (Lulu), and five younger siblings – lived, studied, and dreamed.

Beyond the Wongs’ front door, a climate of antagonism simmered. Anti-Chinese violence ran rampant, and the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act – which shut America’s door to immigrants from China and denied citizenship to those already in the country – was in full, poisonous effect.

Early on, Anna May was captivated by the lively movie sets, big-name stars, and jampacked film houses dotting Los Angeles in the early 20th century. “At a very young age, I went movie crazy,” she later said. Chinatown was hot stuff in America’s cultural imagination, at once a place of fascination and stereotype, driving Hollywood to shoot films with names like “Parade of Chinese” and “Rube in an Opium Joint” on location. Anna May would skip school to watch moviemakers at work in the neighborhood, hoping to get noticed.

Her break came in 1918 during the filming of “The Red Lantern,” a big-budget flick in need of 600 Chinese extras. A local reverend-

cum-technical adviser picked Anna May, who, after a day of crowd shots, received an invitation from the director to play one of three lantern carriers. Huang notes that while the experience – and the on-screen results – were anticlimactic, the acting bug still bit.

Her debut coincided with the rise of “yellow films” in Hollywood, which narrowly cast Chinese actors “as opium addicts, white slavers, lawbreakers, thugs, and debauchers.” This prejudiced approach – further soured by industry rules prohibiting on-screen kissing between Chinese and white actors – dogged the actor throughout her career.

Despite these head winds, Anna May persisted. For the next two years, she acted in bit parts, rubbed shoulders with industry bigwigs, and even had a romantic fling with director Marshall Neilan. Dazzled by the teen up-and-comer, Neilan wrote a part expressly for her in his 1921 work, “Bits of Life”; the movie garnered strong reviews and landed on the year’s best films list but tanked financially.

In what would become a dismal pattern, Anna May’s co-star in “Bits of Life” was a white actor sporting yellowface. This practice of applying facial makeup or alterations to non-Asian performers portraying Asians frustrated – and later angered – her; it’s why she refused to participate in the predominantly Caucasian-cast movie adaptation of “The Good Earth” more than a decade later.

By 1925, Wong faced a dilemma. “It is hard to get into the pictures,” she remarked, “but it is harder to keep in them. ... You see there are not many Chinese parts.” Diversifying her opportunities, the actor successfully gave vaudeville a try, before accepting a five-film contract with a German director in Berlin.

This leap abroad proved fruitful for Wong. From 1928 to 1930, she worked in Germany, France, and England to increased acclaim if not always favorable reviews. Once in London, Wong braved live theater, her first step in the bumpy transition from silent films to “talkies.” She also dedicated herself to learning German and French, later performing admirably in both languages to the delight of her fans.

The key to her longevity: She adapted, attempted, and adjusted. Huang presents the second half of Wong’s life – including a life-changing trip to China, her struggles with addiction and loneliness, and yet another career transition from film to TV work – with continued attention to the historical setting, as well as concern for the increasingly troubled star. Still, readers may wish for a bit more time devoted to Wong’s relationships with both family members and romantic partners. (For a fictionalized account of Wong’s life that effectively ticks these boxes, check out Gail Tsukiyama’s novel “The Brightest Star,” which was published in June.)

Compelling and eye-opening, “Daughter of the Dragon” applauds Wong as a true American individual – averse to being pigeonholed, dedicated to her work, unafraid of reinvention, and a paragon of perseverance.