So you want to win the New Yorker caption contest? Here’s how in 6 steps.

Loading...

It’s hard to win The New Yorker magazine’s cartoon caption contest. If you enter, it’s unlikely that your caption will be either a finalist or a winner. But that doesn’t deter an average of 5,000 people nearly every week from submitting their ideas for the captionless drawing that appears in each issue.

How hard is the contest? Film critic Roger Ebert entered 107 times before his 108th caption was deemed a winner. He entered 92 more times and didn’t win, before he died in April 2013. Other famous nonwinners include former New York Mayor Michael Bloomberg, composer John Williams, actor and comedian Zach Galifianakis, and journalist Maureen Dowd.

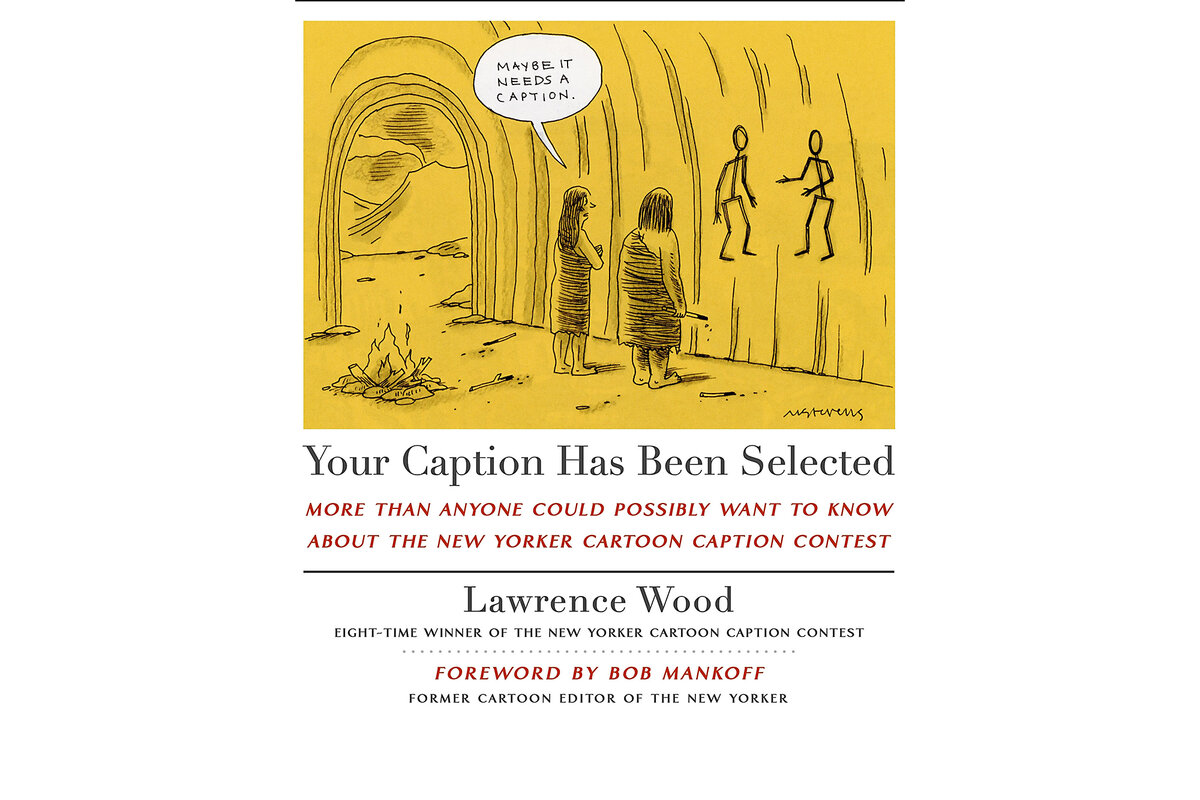

Then there’s Chicago-based attorney Lawrence Wood. Wood has been a finalist 15 times and a winner eight times. “He’s won it the most, he’s the best at it, he’s the GOAT,” writes Bob Mankoff, former cartoon editor of The New Yorker, in his foreword to Wood’s book, “Your Caption Has Been Selected: More Than Anyone Could Possibly Want To Know About The New Yorker Cartoon Caption Contest.”

The rules of the contest are fairly simple, according to the magazine: “We provide an original cartoon in need of a caption. You, the reader, can submit a caption for that week’s contest.”

People ages 13 and older can submit one entry on the magazine’s website or Instagram account. Readers rank those submissions. The New Yorker’s cartoon department reviews the top vote-getters and narrows them down; then readers pick the winner. There’s no prize beyond the glory that goes with having your name and caption appear in the magazine.

This is the 25th year of the caption contest. Wood not only explains its history, but also offers rules and tips for improving your entry. The book is illustrated with 175 New Yorker cartoons – with examples of winning and losing captions. He uses his own great and not-so-great captions to reinforce his advice.

His first rule is pretty simple: Correctly identify the character who’s delivering the line. Wood features a cartoon showing a man and a woman at a table drinking coffee. The man’s head is obscured by a brick wall resting on his shoulders. Some of the top-ranked captions picked by readers included “My ex-wife got most of the house” and “I’m not seeing anyone right now.” But those didn’t win, explains Wood, because the character with a visible mouth – in this case the woman – should deliver the line. The winning caption was, “Do you mind if I bounce something off you?”

Rule No. 2: Make sure you know what’s happening in the cartoon. Wood wrote a caption showing what he thought was a tray of scones being offered to a man and a woman by the Grim Reaper. The man (according to Wood’s caption) says, “Fine. More for me.” But the cartoon’s artist drew lemons, not scones, and the winning caption was, “He says making lemonade is not an option.”

Other rules include some excellent writing basics:

Don’t just describe what’s happening in the cartoon. Tell a story.

Accept the premise of the cartoon, no matter how outlandish, but ensure that your caption makes sense within the parameters of this premise.

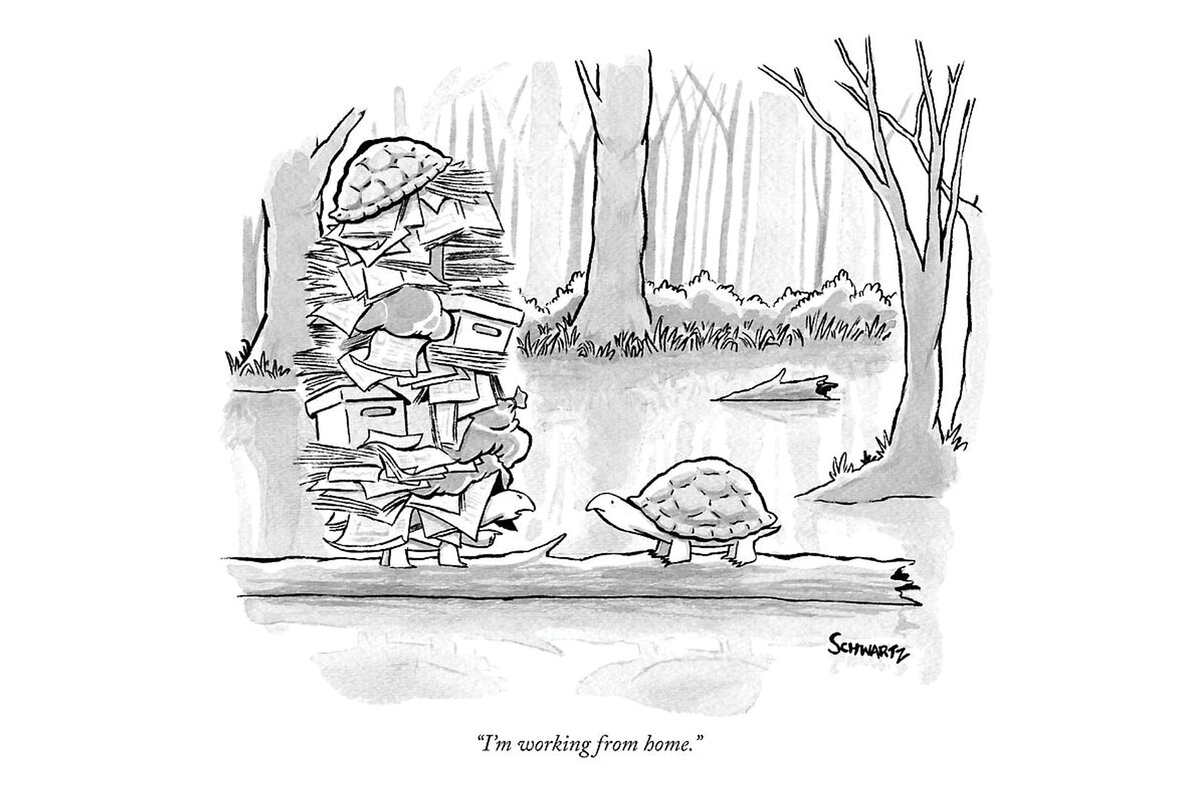

Choose your words carefully. Eliminate unnecessary words. Many captions in the contest are similar, and an extra word or two can decide which captions make the cut.

Note: Not every caption is short. One cartoon in the book shows two cave men chatting. The winning caption: “Something’s just not right – our air is clean, our water is pure, we all get plenty of exercise, everything we eat is organic and free-range, and yet nobody lives past thirty.”

“Most humans enjoy cartoons and winning things, especially things that are statistically difficult to win,” says Emma Allen, The New Yorker’s current cartoon editor, about why the contest is so popular. “And submitting is a bit like getting to throw an opening pitch at a baseball game – for a brief moment, you get to act like one of the pros, whether or not the ball goes anywhere near home plate.”