Writer David Nasaw discusses the turbulent life of Joseph P. Kennedy

Loading...

Womanizing family man, powerful but often-misguided political mastermind, movie industry mogul, would-be president, and one of the most influential, brilliant and aggravating Americans who ever lived.

Only two men fit that description. And only one author has written immensely readable biographies of both of them, plus another one of Andrew Carnegie for good measure.

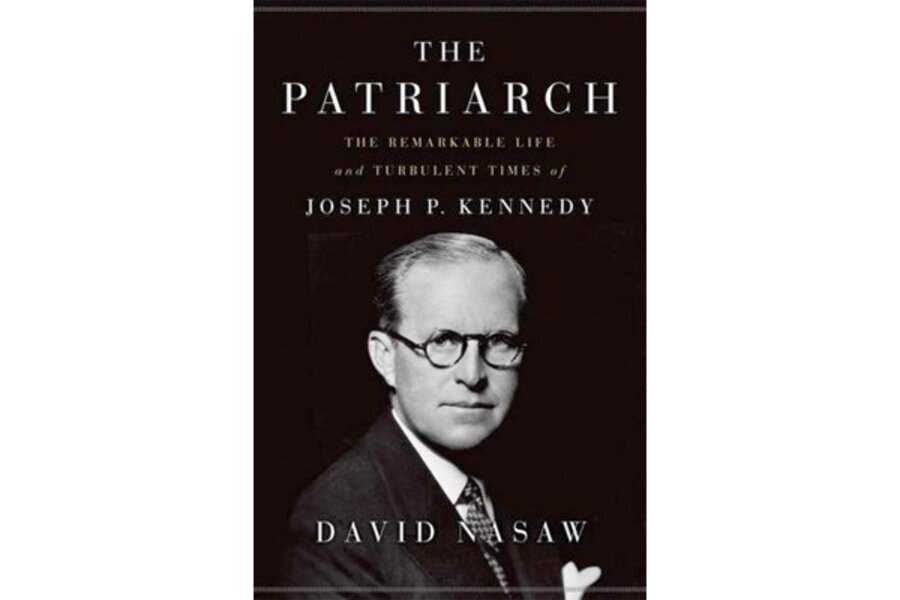

Following on the success of 2000's "The Chief: The Life of William Randolph Hearst," historian David Nasaw has a new bio on the bookshelves with "The Patriarch: The Remarkable Life and Turbulent Times of Joseph P. Kennedy." It's an instant classic, an honest and perceptive look at a man who deserves to be known for more than tragedies and failures.

In an interview, I asked Nasaw about the challenges of writing the book under the eyes of the nation's most storied political clan, the battles that Joseph Kennedy fought, and the ultimate verdict on an extraordinary life.

Q: What drew to you to the story of this man whose children include a president, an attorney general, an ambassador and one of the most storied senators of all time?

The family asked me to do it.

I met with Senator Ted Kennedy to talk it over. We met in the Senate office building, and we had lunch with his two Portuguese water dogs, who came to the Senate on Mondays.

I spent a good long time trying to convince the senator I shouldn't write the book. I'm a crazy obsessive researcher, and I was bound to turn up something that wouldn't make the family happy. And I said it wasn't unlikely that by the time it ran, some Kennedy would be running for office.

He said all the bad stuff is out there, like Gloria Swanson [with whom Joseph Kennedy had an affair]. Everybody knows the dirt, but if a historian writes this book, he is going to come up with a much more credible portrait of his father than what's out there.

My conditions were firm, and I said, I'm not going to budge. I want full access to everything, including all the papers that are closed to researchers and stored at the Kennedy library. You and your family and your lawyers will see the book when it's finished, not before.

Q: Wow. You were really laying down the law, right?

You don't lay down the law to Ted Kennedy.

I said it's not in my interest to spend five to six years on a book and get to the end and have to bargain with some lawyer to include a sentence I found in a letter. I just said I'm not going to do that.

He said fine.

Q: To some people's eyes, Kennedy comes across as such a villain. Even though you write that he wasn't actually a bootlegger, he was definitely a womanizer and a ruthless businessman and political operative.

Did you find anything that would make the family unhappy?

I don't know what they expected and didn't expect. On the whole, the book is as the senator through it would be. It's much fairer and more balanced than others, and it presents a real-life portrait of a man rather than some villainous caricature.

I undertook it because I saw very quickly that I could use the life of Joseph Kennedy to tell a larger story about the twentieth century. Here's a man who works in shipbuilding during World War I and then is a big stock trader during the '20s boom and goes to the Hollywood as a studio when the silents transitioned to talkies, and then is a Roosevelt confidant, head of the Maritime Commission, chairman of the Securities and Exchange Commission and ambassador to Great Britain.

Q: This is all especially remarkable considering that he was an Irish Catholic. Amazingly, that wasn't even a plus in Boston itself during his early years. How did that play out?

He was an Irish Catholic from East Boston who learned when he got out of Harvard that he was an outsider. He'd have to fight and claw his way inside, and he could trust no one along the way except family members and maybe a couple other Irish Catholics.

Fifty to 60 to 70 years ago, America was more divided than today. It was divided into ethic and religious tribes. Every group had its place in this pecking order. He lived in that world, and he had to find his way in it.

Q: And transcend it?

Yeah! The reason why he's such a great character to write about, unlike other outsiders who fight to get inside, is that once he gets inside, he refuses to play by the rules.

He has such self-confidence that he's convinced he's always the smartest guy in the room, and he's not going to follow what anyone else says, not even Roosevelt.

As a result, he ends up on the outside again.

Q: What did you make of his transition that landed him in positions of power in government in the first place?

While this country has been through bad times over the last couple of years, I don't think we're even close to understanding the fears that people had during the Great Depression.

They were not simply fears that the economy was not going to get better. Among a large part of the population, there was a real concern that if the Depression was not cured, this country would go the way of Germany, Italy and the Soviet Union. People in need would abandon capitalism and abandon democracy.

Kennedy was motivated by these fears to support Roosevelt. This is a remarkable part of he story: To become the SEC chairman and, to save capitalism, he realized he had to rein in the Wall Street bankers and traders. He outlawed the practices he'd use to make his millions.

Q: What about his still-controversial work as the American ambassador to Great Britain and his opposition to involvement in World War II?

He made two outrageous mistakes.

He believed that American support of the British was going to destroy the economy and would lead to some form of regulated economy and dictatorship. He couldn't imagine the British were going to win the war.

The second mistake was that he believed Hitler was a reasonable statesman. Kennedy still believed you could make a deal with Hitler, and he believed he could do it.

This was about his fear of war and the cataclysm it would bring – not just the lives lost of a generation of young men, but the destruction of the economy and of representative democracy. He thought this was coming.

Q: How did he manage to have such extraordinary children?

Every child got this sense from him that "I've struggled, I worked hard and I struggled for you. I made enough money so you each have million-dollar trust funds. I expect each of you to do something with your lives – not to make money, but in public service."

It's an anomaly, because strong fathers don't necessarily yield strong sons. But all of these kids were remarkable, all independent-minded.

He's a incredible father, there's no doubt about that.

Q: Was there a dark side to the drive he instilled in them, which seemed to lead to adultery and other problems?

A: When I read the histories and look at them, I think that's rather overblown.

He had nine children; one was [mentally disabled]. In the other eight, there were bad marriages and good marriages.

Yeah, there was womanizing and there were troubles, but I don't know if it's so remarkably out of the ordinary. The trouble that falls on this family, the disasters, come from the outside.

Q: This man reaches incredible glories, loses child after child and ended up a crippled invalid who's helpless as his world falls apart. Do you see him as a tragic figure?

I think I do. But I don't know whether it's a Shakespearean or a Greek tragedy, if it's his own lofty ambitions or the fates that do him in.

Here's a man who lives for his children and who triumphs when they triumph. To lose four of them, five if you count Rosemary [who was mentally disabled and underwent a disastrous lobotomy], that's tragedy.

Then he has an estrangement from the Catholic church when the hierarchy does not support Jack in his bid for the presidency. That was a betrayal of the first order.

And then the stroke.

If this was fiction, nobody would believe this strong, articulate, debonair man, who dressed immaculately, would spend the last eight of years of his life not only unable to communicate, but a crippled monster of a man, frightening his grandchildren.

Q: What about his triumphs?

When his son is finally elected, it's a bittersweet election because so many white Anglo-Saxon Protestants voted against him, but he was elected.

How could a man not savor the fact that he had sons as president and as attorney general and Teddy, after some tough times, was putting his life together? And all the daughters seemed happily married?

He had lived a full life. There were certainly triumphs.

Q: Do you like him?

There's no easy answer to that. There are things I like about him, and there are things I don't like about him.

In the end, I'm thankful that he's so fascinating. I spent six years with the guy, and I was never bored for a minute.

He was unpredictable, quirky and colorful, with a great use of language and sense of humor. That kept me going, and for that I am eternally grateful.

Randy Dotinga is a Monitor contributor.